What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman

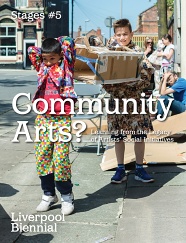

In this writing I seek to detect a few precursory concerns that may inform an initial response to the question, ‘What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned? My text is guided, in part, from previous experience and otherwise by reflective thought inculcated by the ‘Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists’ Social Initiatives’ conference, convened by Liverpool Biennial and Andrea Phillips. The title of the conference itself has been a useful informant. It evades a simplified demand for a reprisal on behalf of an increasingly obscured field of practice, it usefully points towards possible entanglements.

What I hope to do here, firstly using Glasgow as an example, is entangle by tethering marginalised Community Arts legacies back to a preponderant narrative being offered of the city. I move to a broader questioning of how we produce strategies for the production of history-making amidst the punitive restrictiveness and conventionalities inherent to neoliberalism, taking into consideration the broader genealogical possibilities of re-constituting artists’ commitment to social initiation as identified in the conference title. I then shift towards a description of the neoliberal project’s attack on communitarianism and begin to suggest that it may be relevant to unravel some of the rhetoric regarding the commons being applied between Community Arts and arts’ institutional practices in order to consider some distinctions of vulnerability. I then question aspects of the impulses of alternative pedagogical strategies as applied in the social turn within arts programmes and suggest some initial examples of precedents that are being ignored, but which are potent with the history of radical imagination. I begin to touch on the question of organisation, suggesting that perhaps we are so busy in the re-purposing of institutions, amidst their existing structures, that we have not sufficiently identified what we can learn from the generative organisational practices being instituted by artists, beyond legally-constituted organisations, and for which antecedents may exist in the legacies of the Community Arts movement and furthered stratagem in contemporary formations of social practices.

***

To address the notions of legacy and entanglement, I want to mention the influence of David Harding. Following his time as a tutor on the Art and Social Context course at Dartington, David then founded and led the influential Department of Sculpture and Environmental Art at Glasgow School of Art in the late 1980s for over a decade. A key premise of this course was that “context was 50% of the work”, an influence of the work of the Artists Placement Group, which had been active in Scotland. Harding was previously Town Artist for the new town of Glenrothes between 1968-78, paving the way for community engagement via art processes in issues of planning, social housing, architecture and the conception of how to live in built ‘newness’.

After graduating in the mid 1980s, I worked as an arts educationalist for deaf-blind youths whilst supporting a practice that was initially performance based, but beginning to seek strategies to address issues that were effecting Glasgow at that time, with its mercantile history, but then current finalised decimation of the ship-building industry via Thatcher and the social exclusion and economic impoverishment of many of its communities, including that from which I come – the working class.

At the same time, many of my peers in the city were beginning to develop processes towards artworld visibility and the potential for the commercialisation of their art, what Hans Ulrich Obrist (in 1996 when Douglas Gordon was awarded the Turner Prize) referred to as “The Glasgow Miracle”. There was no miracle, only hard work conducted by artists and artists-organisations combined with institutional support. Curators such as Andrew Nairne and Nicola White offered exhibition platforms to recent graduates, mostly those engaged with neo-conceptualism, which followed pretty immediately after Glasgow School of Art’s then Head of Painting Sandy Moffat’s re-championing of figuration by those named the New Glasgow Boys. On reflection, this ‘miracle’ we may now consider as a filtering system that has created a domineering historiography, chronicled in publications such as Sarah Lowdnes’ book Social Sculpture: The Rise of the Glasgow Art Scene (Luath Press, 2010) and reflected in the 2014 Generation [1] exhibition project which surveyed 25 years of Scottish Art, in both of which the many histories of Community Arts practices in Glasgow and Scotland are rendered into obscurity.

Knowing something of what I was up to as an artist, producing works with a queer bent that examined the coercion of vulnerable publics, but also understanding that the post I held as an arts educationalist for the deaf-blind was potentially itself a radical appointment in the history of disability, arts education, Harding invited me to begin what became an almost ten year-long, but intermittent, relationship with the Environmental Art course as a recurring visiting educator. In a sense I can say I went to college in the ‘80s but actually trained in the ‘90s with Harding and others then working in the department including Peter McCaughey, Ross Sinclair, Bryndis Snaejbjornsdottir and Ruth R. Stirling. The reason I refer to Harding is not so much about David himself, despite my assertion that he is an acknowledged key figure, though perhaps this is problematic in his significance being defined in the measurement of how many Turner prize nominees and winners were educated by him and in the department. Rather, Harding is a practitioner whose narrative shifts from his early work in art education in Nigeria, to 10 years in Glenrothes, to the distribution and fostering of debate on art and social purpose in British art education.

It was at Glasgow School of Art that the work of (to give some examples): muralists on the Tijuana border and Derry’s Bogside; Joyce Laing’s work at the Barlinnie Prison Special Unit; the Artists Placement Group; the Tape-Slide and Radical Print workshop movements including Edinburgh’s Tape Slide Workshop; American activist practices amidst the AIDS epidemic; revolutionary art from Nicaragua and Venezuela; the politics of indigeneity and activism of First Nations peoples and artists; literature by Suzi Gablik, Carol Becker, Mary Jane Jacob, Suzanne Lacy and the pedagogical precedents of W. E. B. Du Bois, Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal and many others really entered my frames of reference. Students were navigating the history of site-specificity and developing strategies for its development, through a simple pedagogical model, The Public Art Project, by which students had to select, negotiate and navigate a site, its stakeholders and communities in order to think through their positions, responsibilities and agency as artists, amidst the blighting of Scotland through Thatcherism. Many of those who have become prominent as being educated in this department then applied these negotiation skills to entering existing art world paradigms as opposed to imagining alternatives. Despite this there are many other graduates from there who have sustained communitarian practices but are less lauded than their Turner-prized peers.

Whilst Glasgow reached towards its 1990 European City of Culture status, deeply criticised in the city and lauded simultaneously, we were encountering the beginning of a regeneration process, in which art is often cited as a role-player. The narrativisation of the art of Glasgow has often been filtered through exemplars such as Transmission Gallery, which offered visibility and internationalisation for artists. Consequent logic has argued a promotion of Glasgow as a city in which artists could be domiciled yet capable of developing international reputation at ‘blue-chip’ level in terms of commercial gallery representation, and within the circuits of high-end institutions whilst being sustained by a highly networked community of artists, often written about now as if it were an urban artists’ colony.

However, these factors and their dependence on the individualisation of specific artists’ career trajectories can only be seen as one mode of valuation, and pervasive to a particular reading that diminishes our consideration of the rich picture of communitarian practices, which existed previously or ran in parallel to ‘the miracle’. There were numerous local initiatives such as: the Gorbals Art Project, the work of the Garnethill Muralists later re-developed in 1990, Castlemilk’s Fringe Gallery in its shopping centre, the Scottish Mask and Puppet Centre, Glasgow Film and Video Workshop, Art Link in Edinburgh, Stella Quines, Project-Ability, Art in Hospitals, theatre in education companies such as Birds of Paradise Theatre Company, the children and youth focussed work of Giant Productions and the provision to communities and artists alike by places such as the Dolphin Arts Centre, which ran alongside the city centre’s Third Eye Centre, as two exemplars of the post-war Arts Centre movement, which was as much about community as it was about art forms.

It is important to note that that Glasgow City Council had arts officers in place across neighbourhoods throughout the city, with a mission to embed arts and culture with communities and were thus providing activities in libraries, schools, community centres and youth clubs but also financially supporting artist-initiated projects in communities, including the three-year long Arts is Magic experiment on developing art-informed curricula at Chirnsyde Primary School in Glasgow’s Milton. Glasgow Sculpture Studios’ resident artists often developed social and community projects throughout the city, including those by a generation of women artists trained by Wimbledon School of Art to have professional welding qualifications who were then able to pick up work in the dying shipbuilding industry, which influenced the politics of such community projects.

The Zero Tolerance campaign against domestic abuse and violence, the Glasgow Women’s Library and Castlemilk Woman house debated inequality and exclusion in communities. The feminist drumming initiative She-Bang marched the city. The advent of HIV/AIDS brought initiatives by health, advocacy and lobbying groups, which coincided with programming by then Tramway curator Nicola White, who paid attention to art addressing AIDS from the USA and mounted large-scale exhibitions and symposia in a city in which Deaf people were contracting HIV with higher percentages than the hearing populous owing to most health literature being text-based and inaccessible to sign-users.

Nikki Milligan drove access to radical international, activist and queer performance practices through the National Review of Live Artand her programming at Third Eye Centre and then its incarnation as C.C.A. Artists committed to advancing the city’s important social photography histories founded Street Level Gallery, its own importance often marginalised by the fetishisation of Transmission. Publications such as Variant Magazine interrogated the capitalisation of culture and its relations to the public sector, whilst other publishing initiatives with welfarist, anarchist and workerist politics came out of community activism in neighbourhoods such as Clydebank. Art and artists’ organisational practices also related with campaigns for LGBT, womens', race and disability rights and with the peace and anti-nuclear movements in Scotland. These all rest in relation to a Community Arts movement which we struggle to see any real comprehension of in contemporary writing of Scotland’s recent art histories, and which on a UK-wide basis, we still await a major ‘exhibitionary’ survey or comprehensive publication to catalyse further debate.

Overall, as a legacy, I am talking firstly of less than 25 years of history that is already being erased; and secondly as if people are still not working in Community Arts, but they are. I think we also have to acknowledge that, in the UK at least, we are poor at writing our radical histories. A lack of resourcing intensifies amnesia, and for those of us in this history, we can assert that our experiences are meaningful, our knowledge vast, but our resources to make our struggles chronicles and dissemination possibilities are weak. Perhaps we need to strategise more broadly on the question of how we re-constitute legacy?

***

In a 2012 curatorial initiative entitled A Rally of Speeches, moderated by Andrea Phillips and organised by New Work Network, I sought to bring together speakers whose work I believed was significant but obscured, possibly purposefully. These included Marlene Smith, co-founder of the BLK Art Group, speaking to its importance in catalysing a commons. Simon Watney spoke for the first time ever publicly (he’d never previously been invited to) on the creative strategies of OutRage; Kate Hudson, Chair of C.N.D. addressed the campaign’s relations to art, direct action and the graphic histories of Nuclear disarmament materials; Ilona Halberstadt and other members of the Scratch Orchestra demonstrated modes of collaboration and democratisation of art beyond technical accomplishment. Jess Bainesaddressed the histories of the UK’s radical feminist print workshops. Many of these people had never been invited to speak publicly about these manifestations.

I think that it is important to also recognise that when we begin to look at these histories we should potentially view them with respect for the specificities in their ideologies but also through an intersectional prism. The term ‘community’ should not solely be read as like minded people positioning themselves in identitarian terms, but should be read in relation to our capacity to position ourselves in proximity to alterity and difference, to be together, whilst recognising the necessity to lean towards and incline towards difference, confrontation and conflict.

We need to consider how to understand a larger-scale history of practices that have developed sanctioned and unsanctioned strategies for political imagination during intensified, or indeed systematised, converse strategies for inculcating de-imagination such as our moment now. In doing so we need to consider what we mean by legacies, periodisation, heritages and genealogies. Are we sustaining disavowal through particularised modes of discrimination of artistic practices and supporting continued amnesia by ignoring antecedents that may matter to our cause?

It may be useful to re-navigate to shift view and provide an alternative genealogic proposition on the social practices of artists within which specificities of the Community Arts movement can become entangled. This may include those, for example, who are not only facilitating the creativity of others, but artists who were at the forefront of other societal formations via the manifestation of progressive art in the developmental histories of our public goods. Perhaps there are arguments by which we could extend the reach of what we may mean by the coalition of art and community, through consideration of the role of artists in the framework of the advent of the Welfare State and pillars such as the N.H.S. or Education with examples such as Barbara Hepworth’s Hospital Operating Drawings of 1946-8, or via design by Norman Hartnell’s nurses’ uniform for the new N.H.S., or the Schools Print series of auto-lithographs commissioned internationally by Brenda Rawnsley and distributed throughout state schools. There are countless further examples that offer us ways to think about community, art, and organisation into which the histories of Community Arts may be woven.

Conversations such as the one that underpinned the Community Arts? conference are only beginnings, and here we may have some prefatory work from which to develop.

***

An argument that informs some of what I want to raise is that we are currently living in a deeply politicised and economised fundamental problematic that results in what Henry A. Giroux [2] and others describe as ‘de-imagining’. By which I mean that consistent demands to conventionality are supressing and de-legitimising potentials for alterity and actively limiting how we envisage the ways in which we can be together, what we can do together and what community-centric methods and models are to be made possible. This may lead less, perhaps, to the question of what types of organisations we should have, but could open more to what types of organisational practices can we imagine?

The potential for imagination is being controlled through the privatisation, commercialisation and capitalisation of many elements of our democracy. It is occurring in gentrification and the diminishment of social housing; economically controlled access to employment, childcare and to all levels of education, including informal education, itself a very important factor in the Community Arts movement. Military, police and prevailing media outlets control the capacity to protest and dissent, and regulate direct action and its representation. The consistent privileging of the wealthy, decision-makers with vested interests, allows them to effect policy and strategy negotiations and implementation. Favouritism for white knowledge assumes that its practices should be maintained and unquestioned. The curtailment of workers’ rights and access to the resources for an intellectual life are conducted through de-unionisation and impoverished working conditions. The inhibition of human rights and the dismantling of benefits and welfare provision produce panic and a constant sense of living precariously close to the hole that’s been purposefully dug. These strategies run in tandem with an increased commercialisation of art and its institutions including the unregulated global force of the art-market to which marginalised, at risk, vulnerable and disadvantaged people are of little concern.

These factors are engaged to generate fear, exclusion and complacency and make us financially and time impoverished in ways that actively attempt to constantly disengage us from critical thought and action, and from each other. They generate and foster an erosion of our belief, commitment, access to, or even awareness of our rights to public goods such as education, health services and aspects of law support. Our collective ownership of public institutions is being reduced and our roles not only as consumers but also as formers and reformers; as producers, co-producers and co-participants; as organisers, mediators, facilitators and gatherers being constantly arbitrated through value systems that allow only for metrication and financialisation. The potentials that exist in the notion of community are thus being eroded, and de-imagining is a neo-liberal strategy, by which we are being encouraged to turn away from radical potentialities, or placed in fear of them, or made to de-prioritise them through struggle being replaced with survivalism.

I want to posit that whilst we think about the potentialities of publics within Community Arts, we should also be considering that participation could be oppressive as well as liberating and emancipatory. I think that we need to caution ourselves in the way that we currently construct the notion of participation, its languages, methods, rhetoric and applications that may allow us to call into question what we are participating in, for whom and in what direction; and in doing so what we are discriminating against.

I believe that the capacity of communities to focus on their conditions is essential to sustaining imagination as a political project. I think it contributes to the right to ask vital questions about work and labour, about the diversity of our people and cultures and about heritage-criticality in legacy-formation. Such capacity informs how to progress through challenging the frameworks of our art institutions, our ownership of them and abilities to be present to, and within them.

It allows us to identify and address the multiple layers of filtering and sifting systems at play in education. Fundamental to the project of de-imagining is, as I have alluded, access to education, not in individualistic but communal terms and thus toward the fundamental premise of having rights to become educated, to experience co-education, to share access to educational resources and to replenish its systems by which to educate critical citizens through difference and disagreement and not further incubating a culture of confirmation-bias through similarity and privilege.

I want to ask the following question: As potential inheritors of aspects of the legacies of Community Arts, why have art institutions decided to change their rhetoric - and in some cases their organisation frameworks and job roles - from ‘education’ (meaning collective educative projects) to ‘learning’? We can define the latter as highly individualised with ‘learnification’ [3] discussed as a subjugation of being collectively involved in the project of education itself and instead implementing a mode of individuality that can carry forward aspects of the divisionary strategies implemented by neoliberalism.

I also want to potentially question the viability of fetishising ‘alternative’ pedagogies within art and education, at this moment, and to acknowledge the fact that within the social and curatorial turn around education within art’s social practices, we are witnessing a preponderance of so-called alternative art school models, including as temporary insertions into art programmes. For me, the consequent impact should be considered, not on the potentiality of these as alternatives to a squeezed state education, despite the histories they claim to re-present, but whether those responsible for the replication or recall of such radical routes are actually engaged in a mode of conservatism by turning their back on the fight for state education, and class access to it, including at H.E. level, by creating a parallelised as opposed to entangled system.

What actually are these alternative art schools – whether ‘independent’ or as tropes in contemporary social turn curating, including inside art institutions – doing politically to the concept of state education at a moment of constant erosion of access to the most basic premise of education as a public good? Why do examples such as Black Mountain College re-iterate?

I want to suggest that there are other considerations beyond the histories of Black Mountain, Dartington, Summerhill and Kilquhanity Schools and the predominant discussion of male education reformers that need to be considered when invoking radical education models and their histories, about which the social turn can also be thought to be in a state of amnesia. Why are women like Dora Russell who founded Beacon Hill School not discussed? Why are we not discussing the work undertaken to reform the oralist tradition in deaf education in the UK? Why are we not talking about the Appalachian Highlander School that educated civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Fannie Lou Hamer in direct action strategies via its Citizenship School Programme? Why are we not paying attention to the Burston Strike School, the site of the longest strike in the UK, conducted by children in support of their leftist teachers, the survival of which and actual premises were built on union and leftist support? Why are the stratagems of Canadian aboriginal activists and their colleagues engaged in demanding and contributing to the 2015 Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and similar processes in Australia, not informing us more when we think of radical pedagogy and its assumption in art institutions and their public programmes? Why are we resistant to learning from the struggles conducted by and models originated in the Black Education Movement [4] in the UK, by which people were developing supplementary education to address institutional racism and whitewashing within our education structures. Why aren’t we being informed by our histories of cross-cultural programming strategies in community spaces such as Hackney’s long-term, but now closed, space for community action, Centreprise. I believe that the need to interrogate institutional racism and whitewashing in education has not ended, and that it is still deeply at work in our schools, colleges and universities. These movements for reform and their communitarian routes and the struggles fought are, as I far as I am aware from the literature on art and the educational turn, not being considered as valid to its discourses in the need to debate the persistent of violence towards state education.

***

The art institution in its shift to the social turn has moved towards modes of participation that, perhaps, are more easily consumable within the logic of a capitalising culture and often sustains the heroisms of individualised authorship.

Since the late 1990s attributes of being enquiry-driven, co-productive, participatory and pedagogical, and politicised have influenced the advent of discourse on what has been determined as ‘the curatorial’, not necessarily distinct from exhibitionary formats but also not necessarily inclusive of it, and comprising of evental actions such as reading groups in reading rooms; seminars, colloquy and caucuses as forms of assembly and generators of discursivity; socialities implemented through collective work; and the assimilation and re-occurrence of strategies and ideologies relating to radical education histories and civil rights movements. The ‘curatorial’ to date has paid scant attention to any pre-figurative concepts generated by the Community Arts movement, despite its strategies being circumscribed towards a re-purposing of art institutions and their constituents.

Through a research project at the Valand Academy [5], where I work, with Mick Wilson and Julie Crawshaw, I am interrogating the concept of artist-organisation. An initial observation, on which I have future work to do, is that in the ideological, theoretical and speculative nature of the literature of ‘the curatorial’ limited representation is given to the grass-roots organisational work undertaken by artists and communities. I would argue that the methodologies by which ‘the curatorial’ suggest expansion of art via durational, longitudinal, pedagogical and embedded means have been generated both within Community Arts movement and the broader work of artists-organisation for a long period of time, but this is not being sufficiently acknowledged as a line is being drawn that disentangles antecedents within the Community Arts movement from its discourse. What I am concerned by is the attention paid to the impact and potentialities of artist-organisation within the literature of ‘the curatorial’, in which the artist’s role is expansive in institutional terms but reductive towards the types of experiences many of us share here today as those with roots in social arts that operate in community contexts, which may include the institution but is not always dependent on its validation or its resources.

Community Arts has been concerned with the joint capacity and potential of communities to make art that activates its members to collectively gather to identify, describe, share, discuss and dissent against its challenges and conditionings and often within the physical localities of their lives. It challenges modes of aesthetic validation through enmeshment of professional and non-professional makers and thus is multiply authored though occassionaly anonymous. Via processual, grass-roots and horizontalised communal dynamics the problematics and discontents of attempting to parameterise or extend the cultures of community-making - via arts practice - run alongside changes being implemented in the lives and circumstances of these communities, their socio-economic order determined by the logics of policy, strategy and forms of governance that also effect their cultural, social, political and economic lives via systemisation.

A concern, that may need further interrogation - between Community Arts and the social turn in the programming of arts institutions - lies in the barriers that exist in the concept of the commons. It may be worth reminding us that the commons is not necessarily about shared community ownership of land or resources, but of communal access and dependent on the implementation and upholding of legislation and custom and practice for access to be sustained. Therefore, with a history in feudalist economies, the commons as indicative of rights of way to space and supply is predicated on a contingent and vulnerable confluence of ownership and the allowance of access. A custom that is susceptible to disenfranchisement and capable of being revoked through intensified commercialisation through the privileging of private ownership and capitalisation. This may include Arts Council England’s various schemes to incubate and encourage philanthropy and commercialisation resulting in art’s institutions and their programmes being further contoured through the influence of the art market, private donation and corporate sponsorship, which also effect the delimiting of the commons. Whilst we need to debate how we protect the potential of art’s institutions, also under threat to conventionalise, homogenise and commercialise (amidst which ‘the curatorial’ and its speculative characteristics are seen to have the potential for a form of repurposing) we may also need to assess particular ideological logics in order to further understand some differentiations of vulnerability between Community Arts and art’s institutions in relation to the concept of the commons.

Pascal Gielen [6] has identified, Community Arts is built upon the facility of a pre-existing and comprehensible commons. He claims Community Arts exist, in part, owing to the commons but insufficiently addresses the dynamics and vulnerabilities of access. A similar claim is also made via ‘the curatorial’, though a slight yet significant differentiation exists in that aspects of its rhetoric. A claim seems to be being made that in the re-purposing of art’s institutions, ‘the curatorial’ is able to stretch the dialectics of ownership and access and foster a process through which they become propagative of a new shared commons, one in which their own increased commercialisation is disguised and diffused. Thereby, to a degree, a line is being drawn between Community Arts and their access to resources and their manifestation in now-vulnerable locations, such as community centres, libraries, youth clubs, working people’s clubs, health centres. Socially engaged and participatory arts practices, are being brought into the stewardship, mediation procedures and value systems of the art institution, and its increasing relations with capital, whilst claiming to be commons-generative whilst Community Arts is being evicted from its spaces, ideological and physical. I think we require future discussion of what is being protected and what is being seen to be superfluous in the fight for the commons; and whether, as Andrea Phillips has pointed out to me, current fixation on the concept of the commons is itself founded on a flawed idea of egalitarianism, and potentially responsible for the erasure of struggle.

***

I would like us to also consider that, when we talk about the nature of participation and Community Arts, we often talk about dialogue, confidence raising and trust; but we rarely talk with detailed consideration, of how trustworthiness is actualised. I’d like to suggest today, as I did in my 2013 publication on the inter-generative potentialities of trust and dialogue [7] that trustworthiness is made manifest through the mediation of uncertainty and not necessarily through the adherence to predetermined pact and promise.

It may be more trusting to allow ourselves to formatively scope and parameterise how to navigate uncertainties and variables together when new knowledge and experience arises, to legitimise the changing of our minds as impacts are provoked, and to collectively re-purpose our strategies as we incrementally assess their efficacy than it is to steer towards an unknown but hopefully reachable future by clinging to pre-determined contracts made inside the outset of the problematic that is to be challenged. If that is the case, then how shall we generate the imagination of trust between us? What new rules and parameters can we determine to work and live together in trust-centric as opposed to risk-averse ways? What principles shall we bring forward as our conditions for doubt? And, what existing values can we eschew?

As an example of what I mean, let me introduce a project that I worked with for several years, Anniversary - Acts of Memory [8] when the late Monica Ross committed, or more correctly attempted (it is very important that it is an attempt) to commit to memory and publicly recite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights via performances across multiple sites and contexts, cultures, countries and languages with individuals, social action groups and multiple communities – taking forward many of the legacies but upholding and recalling to use many of the priorities of the Community Arts movement. Monica very sadly is no longer with us but I wanted to make her present in this context. On the day she died, Monica completed the cycle, and her commitment to iterating this project 60 times in 60 different sites. Ross was a leading feminist artist and this work, undertaken late in her career, is complex: she advocates on one hand for a universal, but on the other then particularises it in many ways, via language, site, organisation and community. The U.D.H.R. states that we are born with these rights, and whilst they may be intervened in, they cannot be lost or removed: from birth to death we own the right to them, at all moments, and in all circumstances. Thus, a factor to consider is that, each and every time she negotiated the means of production, Ross was transacting via the perceived significance of a document that actually seeks to lay out the way that our Human Rights are extant, cannot be taken from us, and thus every person engaged in that transaction with her was already in possession. Acts of Memory, I believe, is significant in that it is suggestive of organisational practices, initiated and led by an artist, that were not an organisation in the usual formal or constitutive terms – but one productive of trustworthiness, whilst many other forms of legitimised organisations fail to achieve this.

Let’s move forward.

[1] http://generationartscotland.org/. Accessed: 2 July 2016.

[2] Henry A. Reclaiming the Radical Imagination: Challenging Casino Capitalism’s Punishing Factories. http://truth-out.org. Accessed 30 August.

[3] A key thinker on ’learnification’ is Gert Biesta. http://www.gertbiesta.com/

[4] Records of the Black Education movement are held at London’s George Pasmore Institute.[5] http://akademinvaland.gu.se/english/research-/rese....

[6] Gielen, Pascal. Introduction. In Community Arts The Politics of Trespassing, Paul De Bruyne and Pascal Gielen (eds). Amsterdam: Valiz. 2013.

[7] Bowman, Jason E. Esther Shalev-Gerz: The Contemporary Art of Trusting Uncertainty and Unfolding Dialogue. Art and Theory Stockholm. 2013

[8] Ross, Monica. http://www.actsofmemory.net/. Accessed: 17 July 2016.

Download this article as PDF

Jason E. Bowman

Jason E. Bowman is an artist with a curatorial practice. He is a researcher, writer, educator and Programme Leader of the MFA: Fine Art at Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg. Bowman was one of the first arts educationalists for the Deaf-Blind in the UK and has worked with communities his whole career, through participatory methods, to interrogate the coercion and violation of publics. He recently completed a role as a co-researcher interrogating the co-generative potential of trust and dialogue via the practices of Esther Shalev-Gerz, and is now at work on a three-year long enquiry, via the curatorial, into artist-led cultures. Previous curatorial activities include the official presentation from Scotland at the Venice Biennale (2005), the inaugural European career survey of Yvonne Rainer and Monica Ross’ Anniversary – an Act of Memory. His artworks have been commissioned by Franklin Furnace (NYC), ICA (London), Tramway (Glasgow) and Whitworth Art Gallery (Manchester) amidst many others.

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon