Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall

Close up of Oliver Plender annotations on Ed Webb-Ingall Looking Backwards in the Present Document, 2016.

Close up of Oliver Plender annotations on Ed Webb-Ingall Looking Backwards in the Present Document, 2016.

The instigation of artistic projects in neighbourhoods and for community groups, motivated by the potential for social change through increased access to modes of self expression, was what came to define the Community Arts movement in the 1970s. This is not simply something that happened in the past to look back at nostalgically, instead it continues to provide strategies and a language that can be reactivated, built on and learnt from in the present. I am interested in reactivating the ways in which Community Arts projects were originally developed in order to more fully understand and critique them and to ask: what can we learn about the current moment when we attempt this process of reactivation? The methods developed in the 1970s to initiate and evaluate Community Arts projects continue to provide a means to facilitate new Community Arts projects. These past processes, and the materials that emerged as a result of them (videos, pamphlets, newsletters, articles), create a critical and productive utopian impulse; they provide multiple models of resistance, offering a means to understand how individuals might engage in collective acts of representation, providing a framework to explore the role and definition of the word community in new contexts.

Writing on the re-appropriation of archival materials, art historian Paolo Magagnoli suggests that such works provide ‘a resource and strategy central to struggles of all subaltern cultural and social groups… and show possibilities which are still valid in the present’ [1]. The development of contemporary Community Arts projects, triggered by the reactivation of materials and processes produced and developed the 1970s, allows me to draw lines across history. This process of reactivation creates what American artist Sharon Hayes, describes as ‘transhistoric relations’: using historical materials to speak from or through particular historical moments. These materials help ‘to uncover, in the present moment, a given historic genealogy that was wilfully obscured or erased, or to unspool a historic trajectory so that another present or future moment might have been, or might be possible’[2]. Film theorist and historian Thomas Waugh suggests a similar approach to the reactivation of political films ‘whose original political context and thus ‘use-value’ have lapsed, but which may find new uses and engage new aesthetics in new contexts’[3]. I have been developing a number of projects that draw on the history of community video, which makes up part of the wider Community Arts movement. As Waugh proposes, this has involved recovering community videos from the 1970s in order to produce and facilitate new community video projects through meetings, screenings and workshops[4]. Screenings of the original videos to relevant community groups, based on interest, identity or locality, combined with the reactivation of the techniques and approaches carried out in the production of them has triggered the creation of new video projects. The collective experience of making and screening these videos has established a shared language to understand, reflect on and critique the history, processes and aims of community video making.

As a result of these processes of historical research and reactivation I have produced a list or set of instructions that set out to explain how one might initiate and facilitate a Community Arts project. For this edition of the journal I have invited a number of socially engaged practitioners to annotate and amend the list. The list is not a suggestion of best practice or an attempt to erase or smooth over the inherent complications and different approaches to facilitating Community Arts projects but more of a provocation. I see it as a work in progress, like the archival materials and historical processes I borrow from, to be constantly (re)negotiated, annotated and amended by those who use it. The list is a trigger and an invitation to share ideas and demystify processes and practices, the start of a conversation, with the suggestion that it can only ‘work’ when in a process of modification. The versions of the list produced subsequently operate as evidence of the conversations and exchanges that have taken place since its inception; the annotated form suggests a dialogue rather than a fixed position, something which is constantly in motion.

Below is the original list, followed by three annotated versions. Please feel free to annotate the list and suggest amendments and send it back

Full sized image can be found here.

Anna Colin, Curator and Co-Founder/Director Open School East

Full sized image can be found here.

Olivia Plender, Artist

Full sized image can be found here.

Michael Birchall, Curator of Public Practice Tate Liverpool

Full sized image can be found here.

Anna Colin Biography

Anna Colin is an independent curator based in London. She co-founded and co-directs Open School East, a space for collaborative learning in East London, which brings together a free study programme for artists and a multifaceted programme of events and activities programmed by and open to a broad range of voices. Anna also works as associate curator at Lafayette Anticipation: Fondation Galeries Lafayette in Paris, and is co-curator, with Lydia Yee, of the touring exhibition British Art Show 8 (2015-16).

Olivia Plender Biography

In my work as an artist, I often set up situations in which I expect something from the audience. I collaborate, make workshops, performances, installations, videos, comics, magazines, lectures and sometimes curate exhibitions. I endeavour to understand how people form group identities. I began by looking at the margins, at fringe social movements, non-conformist religion and communalism in all its many forms. Subsequently I moved onto mainstream phenomena such as nationalism and consumer culture. Later I began to scrutinise the education system and it’s relation to the work ethic and ideas of value. I am interested in who has the right to speak in public, how the ‘rational’ is defined, which voices are taken seriously and inversely I listen to those voices that are not. My work often focuses on the ideological framework around the narration of history; what we think we know about the past inevitably shapes what we believe is possible in the future. Currently I am running a series of workshops at Open School East, London, and embarking on research into the East London Federation of Suffragettes. In collaboration with local women's organisations, I am hoping to find out what relevance that history has today.

Michael Birchall Biography

Michael Birchall is Curator of Public Practice at Tate Liverpool, and Senior Lecturer in Exhibition Studies at Liverpool John Moores Univeristy. His PhD research has focused on socially engaged art since the 1990s, and the curatorial role in this process as a producer in Europe and North America. He has held curatorial appointments at The Western Front, Vancouver, Canada, The Banff Centre, Banff, Canada, and Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, Germany; and was previously a lecturer in Curating at Zurich University of the Arts. His writing has appeared in Frieze, Frieze d/e, thisistomorrow, Modern Painters and C-Magazine as well as various catalogues and journals.

[1] Magagnoli, Paolo. Documents of Utopia: The Politics of Experimental Documentary. New York: Wallflower, 2015. p.9

[2] Hayes, Sharon. "Temporal Relations." Not Now! Now! Chronopolitics, Art & Research. Ed. Renate Lorenz. Berlin: Sternberg, 2014 p.71

[3] Waugh, Thomas. Show Us Life: Toward a History and Aesthetics of the Committed Documentary. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1984.

[4] The majority of which have been in collaboration with Louise Shelley at The Showroom. As part of the Communal Knowledge programme I have been working with four local groups under the name People Make Videos to address the history of community video practices in London from the 1970s. For more information please see: http://www.theshowroom.org/projects/ed-webb-ingall-recording-programs-for-repeated-playback-uk-community-video-from-the-1970s-now

Download this article as PDF

Ed Webb-Ingall

Ed Webb-Ingall is a filmmaker and writer with an interest in exploring histories, practices and forms of collectivity and collaboration. His current research examines the ways in which video technology operated within social contexts and how concepts of mobility and access intersect with political platforms of community-based activism and forms of representation. He is currently a mentor at Open School East, London and is carrying out a two-year residency at The Showroom, London. Recent projects include co-editing The Sketchbooks of Derek Jarman, published by Thames and Hudson and We Have Rather Been Invaded, a collaborative film project that looks at the legacy of Section 28, commissioned by Studio Voltaire, London. He is also a TECHNE PhD candidate at Royal Holloway University, England, where his research focuses on the history and practice of community video in the UK between 1968 and 1981.

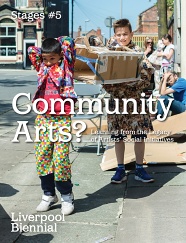

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon