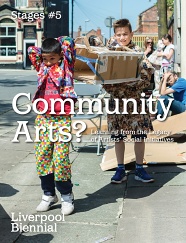

Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). IMI council members outside IMI Corona office, Queens, New York, 2014. Photograph courtesy of the Queens Museum.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). IMI council members outside IMI Corona office, Queens, New York, 2014. Photograph courtesy of the Queens Museum.

Laura Raicovich: Prompted in part by the conversation held at the Queens Museum recently by the Social Practice Queens (SPQ) programme at Queens College, I thought it would be interesting to discuss the tension between social practice, institutions, and Community Arts in the traditional way of imagining community engagement and art endeavours. Perhaps it would be useful to discuss this in the context of Immigrant Movement International (IMI) Corona, from its first phases of being driven by the artist Tania Bruguera, who instigated the project, through to the shift that followed her lessening engagement, to looking to the future.

Preeana Reddy: I’d also like to add another tension to the conversation between social practice, MFA students, and Community Art spaces and artists that work in that context. I think that there is an assumption about who social practice students are that isn’t necessarily true for all programmes and as programmes have gotten bigger and diversified that is even less true. The original social practice programmes mostly on the West Coast were very much traditional MFA students and the new programmes that are coming out of the East Coast, of which SPQ is one but also at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). The latter have a Community Arts programme with the added twist.

LR: Yes, a lot of those students are coming to these programmes from other fields of study. It isn’t like they are coming out of it from traditional MFA programme and finding the route that way. It is more that they have a different set of skills.

PR: These students also have a lot of experience between undergrad and graduate school. They are already professionals or have some kind of other formation before they come to this, and so I think the tension is a different tension than the one that is often talked about.

LR: Right – as opposed to the more often-referenced question of where the art resides and issues of authorship. In this context, these questions begin to fade.

PR: Exactly, and I think that some of the projects, like the people coming out of SPQ, like Sol Aramendi – yes she is an artist in her own right, a photographer, and she is using a traditional art medium – however, SPQ has provided an opportunity to think beyond 'I’m a teaching artist, or my only way of engaging the public is engaging through sharing my primary artistic medium'. Rather, there is a mandate to push artistic practice further and to really think about cultural organising tools and how an artist can be involved in creating a connection with the community based on organisation, and having that project actually come out of the direct ideas in relationship building with members of an organisation alongside aggregating other creative professionals, like bringing application developers into the mix. For example, Sol is not an app developer herself but she did have the skills and social networks to be able to get arts funding and to be able to pull a team together from Cornell and MIT to be bridge builders between traditional worker centres, worker organisations and academia, designers and so on – and that is very different to thinking about what a Community Arts person might do.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). IMI community council members at work at the Corona office, 2014. Photo courtesy of the Queens Museum.

LR: Also, I think that Sol is coming out of the arc of exactly what artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles discussed recently. She stressed a kind of silent sitting with sanitation workers over long periods, wanting them to offer up a way to create a Work Ballet with their vehicles, because they are the ones with the skills that would be used, and inviting that by stepping back, without forcing it to happen: because she didn’t want it to be just part of their job. Since their superiors always tell them what to do, this was a space where they could enact their own creativity within the framework of this co-created artwork. I feel like there is that kind of lineage and that is actually – even though Mierle has had a sustained engagement with the universe of sanitation for a very long time – it is fundamentally a bureaucratic engagement. Yes, it is about the specific people, and she knows all the players, but it is really different from saying ‘I am going to embed myself in this community or this network of community members and evolve a project’. A project like Rick Lowe's Project Row Housing is really fundamentally different from what Mierle’s is doing.

At the outset Tania’s engagement with place and community was very particular and tied into some specific ideas that she had about how community engagement in a very grassroots way would end up speaking to a larger movement that she was interested in instigating. She was also interested in that letting go process between then and now in terms of her involvement, but also in the build-up of the community momentum around their own engagement. This transition is interesting because it has often happened that an artist is engaged with an existing Community Arts framework – that was the tradition in a way, and so IMI Corona represents a shift because the engagement that Tania, I believe, was proposing from the outset was intentionally political.

PR: I think that Tania was working out something new. She wasn’t trying to recreate her existing practice but wanted to act as a kind of provocateur of power relationships - whether as a performance artist or as an installation artist or as an educator or aggregator of creative people. She had done long term projects before, and so I think that aspect wasn’t scary to her. However, I think the embeddedness within a particular community was in perhaps some kind of tension with the concept of what a migrant is to begin with. Often times Community Arts, or community centres, come out of a historical neighbourhood context, and IMI Corona didn’t come out of that. It wasn’t talking about long-term residence, it wasn’t talking about strictly neighbourhood issues and dynamics. It was really looking at the very big picture. Ideas about migration as the human rights question of the 21st century, in relation to something local that involves migrants of various sorts, with the artist being a type of migrant (and Tania very much identifying with that status), as well as questions of the economic migrant and the political migrant, as it were. That all these different migrants are in some senses within this project is a conceptual challenge posed to the democratic nation-state narrative, i.e. that our rights as individuals and human beings are given to us by belonging to a state. That ideal is being challenged both by citizens and the failure of very many nation-states to provide that for their own citizens and therefore the push towards migration for those people to find these rights – only to arrive somewhere else and then be second-class citizens without those types of rights.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-Ongoing). IMI leaders’ retreat at the Queens Museum, 2014. Photo courtesy of the Queens Museum.

LR: And I think also in the context, these questions were hugely relevant five years, six years ago when this project started but are increasingly so now with the situation in Europe and the mass exodus from Syria. We are bearing witness to the reality that borders, while seemingly impenetrable on one hand and really dangerous and precarious to cross, are on another level actually totally invisible and not real. People are arriving because they are so desperate to leave the circumstances they are in.

PR: Similarly, in Central America, violence has precipitated a wave of unaccompanied minors migrating over vast distances. IMI Corona was prescient around this challenge that we are facing globally now, beyond just the US-Mexico border and those ways in which the immigration battle in the United States had been pitched and framed. The challenge for the project at its outset was: here are the big picture questions that we wanted considered by intellectuals of various sorts, as well as home-grown intellectuals who are speaking from their experiences as well as academics and thinkers throughout the world. We asked, 'How do we bring these different registers together and conversation?'. This was important at the outset. So when we were developing the manifesto, for example, it was really important to Tania to have the local folks, the arts community, and people from around the country brought together to join that conversation.

LR: Perhaps it is this interconnection point that the artists forces on the situation. Which is an important distinction from the way that things are operating now, but in that initial phase this was essential to create a platform for action. The development of the manifesto was important on many levels, it may have had more significance to some of the people who were involved in crafting it than others but I think that is always going to be the case. I just wonder if – is that a document that has been revisited at all?

PR: Yes, it has been re-done actually. We don’t call it the manifesto anymore, it’s just our values. But just to go back a bit: everybody saw the manifesto, and even though it was translated into multiple languages it wasn’t clear necessarily to people who weren’t within that process but who were part of the IMI Corona community where it came from and why and how did it to connect to them as participants of IMI Corona and so one of the first things that we did as we were developing the council – the community council of users after Tania’s departure - was to revisit the manifesto for immigrant movement but also other manifestos like the Black Panther manifesto etc. because a manifesto itself is part of a tradition and for them to understand the tradition of why people create them, why are they called manifestos – to have that bigger context.

LR: And to explore what their political value might be, what is the relationship between the manifesto and the dynamics of power.

PR: Right. So the Council rephrased and rewrote the original manifesto as a statement of values, including what they felt was missing in terms of the specific space that we are creating at IMI Corona, as opposed to just a general manifesto for the migrant. What does it mean at IMI Corona today, and how we do our day-to-day work, and how does that translate, and what are the values that we have as community members, educators and so on. I think a lot of it had to do with notions of who can teach and issues of power around that – the kind of learning environment space that people wanted to be in.

LR: In fact, the site of IMI Corona is a site of learning through the many workshops held at the space.

PR: Yes, and this brought out the fact that the most locally relevant of all the activities that was happening at IMI Corona was its function as a location for individual education and empowerment etc., because a lot of the people who were utilising the space didn’t have formal education, or extended formal education, and weren’t in positions of leadership or power. A lot of them were housewives or full-time mothers who might only have been working occasionally. I’m not saying they had never undertaken paid labour, but they often feelt very limited in terms of the realms that they could access beyond domestic space. The powerful idea emerged that at IMI Corona, they could not only access a different kind of learning, but that they also had things that they could share. They could develop themselves as teachers.

LR: …and so provided the space for their own agency.

PR: Exactly. So how do you transform this manifesto for immigrants in the 21st century to what this space is about? I am an immigrant in Queens and a leader in this space – how do these two things reconcile?

LR: So maybe just to go back a little bit and talk about how the space was actually, literally, functioning from the outset – and then maybe how it transformed over time.

PR: The Queens Museum had been organising in the community, and had relationships with various community based organisations. And, we had access to a physical space on Roosevelt Avenue. We were also commissioning artists interested in community dynamics to make projects, and had teaching artists that were with us through the New New Yorkers programme (a project that teaches art skills to recent immigrants in their native tongues) who already had an interest in working with immigrants. We had an empty space that we wanted to populate and create community around, so we imported programmes like the New New Yorker style workshops as well as workshops from other organisations that didn’t have a big enough space. So we invited New Immigrant Community Empowerment, who have a tiny office, to do their workers’ rights workshops there, and brought in the Dreamers of New York State Youth Leadership Council to do their Queens-based work with undocumented youth there, too.

And that was also a model that we used at the Queens Museum. We asked ourselves and others, 'We have space, who wants to use it, how do we activate it?'

So this was one way that we could easily populate a local audience in this space outside the Museum. We then invited Tania to engage with the space, and conceived of her first year being there and living there as research to really understand the local context, which was really important because she wasn’t from the community. She had conceived of Immigrant Movement International when she was in Paris, and there were the riots in the suburbs – that is a very different milieu than Corona. This was also a way for her to get to know and understand the local needs, and how the local community may or may not be involved in the larger project. So there was that, there was also an initiative with Creative Time during that first year. The idea was to speak to a broader arts community – Tania had developed Arte Útil as a new genre of art, and we were asking questions of how we define the work, and so there were several Arte Útil gatherings. They weren’t specifically meant to address local concerns, but more meta-level questions around how can art be useful not in just a conceptual way or representational way, but rather to make it about something and so the criteria of it being time-specific and that it actually does solve some problem as opposed to…

LR: …addressing something very directly.

PR: Exactly, and so there was the sense of figuring out how this is different from previous practice, and what Tania was hoping to accomplish through Arte Útil. This isn’t to say that that is the only type of socially engaged artwork to be made or worth being made, but to distinguish it as a new type of artwork that has a particular set of demands on itself.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). La Escuelita de Pensamiento Comunitario Tránsito Amaguaña at IMI Corona. Photos courtesy of the Queens Museum.

LR: Right. And I think that this is where Tania’s artistic practice diverges from somebody like Mierle’s. In Mierle’s work, the art happens in that moment of interaction. That moment may be sustained for a long period of time, and there certainly is potential for change and shift there, but it is not nearly as direct. Her manifesto is much broader and hits so many different issues like feminism, environmental justice and labour rights, whereas the IMI Corona manifesto was specific on a particular issue, hammering away at some very particular political and economic and social needs around the ideas of migration and nationality and what that means today.

Then, there is a key transition where Tania becomes less involved in the project which is built into the plan from the outset. And so the Council or Consejo comes together in a really robust way, and the work that has been happening over the last two or three years now, not only building the popular education structure for their own self-learning or self-education, but also considering how that has impacted both the structure of immigrant movement and Corona and it’s goals going forward.

PR: This transition was multifaceted. As a museum we needed to figure out what we could commit to in terms of keeping the process going. We can’t take the place of an artist like Tania. However, there are other artists who have flourished within the platform of IMI Corona, and we had to understand what their role would be in the project going forward. What do they want to achieve? How do we support them? There is a community utilising this space on a regular basis who find everyday value there, and so when we get to who those people are and the real value that they see, and what they feel they need in terms of support to take on the project, and make decisions about the project, this is where we as community organisers and Queens Museum try to come in and fill in some of the institutional void.

We as a staff had to think about what are our assets were. If we were committing to it as a staff, then we were committing to it as members of the community and not just as Museum staff. How were we creating art, as well as a world, as well as a local community that we wanted to be a part of shaping. It was a soul searching for us at the Queens Museum because we knew at some level there was a next level commitment. To be honest, the team assembled at the Museum came out of a popular education methodology: a community organising methodology that gave us a particular perspective. Within the Council at IMI Corona, we had structural issues that we had to solve. Some people who had never been involved in either a non-profit or any type of other organisation as a leader, so how did we want to make decisions? What were their roles? What decisions did they want to actually make, and what decisions did they want to leave to us. Those were things that took a long time to explore and resolve.

LR: Having only been at the Queens Museum for a year, and having only seen IMI Corona up close during this time period, one of the super striking things to me is how this project might embody a question like: ‘What is the institutional role of a museum in relationship to a social project like this?’ because at the end of the day it is a social project. There were questions about the transparency of our finances in relationship to the project. Many of the questions that the Council members have had for me since I stared really speak to questions about how structures work, and the implicit power dynamics that surround them. I feel the tensions and power relations intensely, but I also think it is important for us to lend that institutional view to the complexities and idiosyncrasies of non-profit structural life, which is depressing on one level and fascinating on another. But also so that the Council can determine what relationship they want to have with the Museum, and in this respect, I feel very much like Tania: that as long as the Consejo wants to continue this project, the Queens Museum should support it in whatever way we co-determine, and I think that this is a constant renegotiation that has to happen because as the Consejo evolves and shifts. As new members join and past members leave, the face of this relationship is going to change.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). IMI Women’s Health group Mujeres en Movimientoexercise classes in Corona Plaza, led by Veronica Ramirez, 2014 Photo courtesy of the Queens Museum.

PR: The relationship between Tania and the new people is very different than three years ago when a lot of people had a much more direct relationship to Tania. Many people who use this space now have a very hazy, loose understanding of who Tania is and what her relationship to the project. And there is a difference between Tania doing an art project in the name of IMI Corona (such as when IMI Corona joined Occupy Wall St, which Tania was very much involved in - an intervention in Occupy as well as a public intervention) and the Museum bringing another artist in to the project, with whatever they want to do. They don’t have the same relationship to Immigrant Movement as Tania does, and so there is this question of who can do what in IMI Corona’s name. One of the few decisions that we made consciously was that Immigrant Movement International was something that could be continued by Tania under the IMI banner, even when her role in Queens came to an end. In turn, the decision was that the project here in Corona could also be somewhat independent.

LR: Essentially, Tania Bruguera initiated IMI Corona, which then evolved and spun off from the Immigrant Movement International project. Her instigation created a platform that the museum supported and continues to support, even though it may change its form from time to time, as the community sees fit. And of course, here enters the cloudy, sometimes uncomfortable space of co-authorship.

PR: Yes, there has been some confusion about how to connect with IMI Corona. There are many proposals from artists and organisations asking if they can bring a specific initiative to IMI Corona. We have to acknowledge that when a project happens at IMI Corona, it is not just a Museum process, because it involves community members’ time. There has to be something more in it than, ‘ this is a cool art project’, and of course it takes time to develop relationships. So we have said no to a lot of these things even when they are artists that we think are really doing good work, because they have to be willing to invest in this process and to leave behind a residue or skill.

LR: But it goes even further than this because I think now there is an agenda that is coming directly from the Consejo that wants to be addressed as the primary function of IMI, and so as it evolves it may still be the case that people come out of the woodwork saying ‘hey, I have this idea’ and the Consejo is responds ‘yes that dovetails beautifully, lets figure it out’ or ‘well, no, we have other priorities.’

PR: The key is that no staff member at the Queens Museum can impose such a project.

LR: Right. You can make an introduction and see if they think it works within the priorities the Consejo has set out. I just want to point out that I don’t think that this project would have been possible had the Queens Museum not had a long history of organising in the community around the Museum. When you talk about Tania’s year of research, it speaks to that because the only way that there would have been a surround of people to engage with to begin with was due to the community organising process that had been underway for years.

PR: One of the uncomfortable processes has been the necessity to address the way in which a lot of the workshops that happened there (which started organically or have a real relationship with the space) may not necessarily all align with the values and goals as stated by the Council that developed over time. So we had to actually have someone go and visit every workshop and explain the values and how they came about, and how there might be some conflicts between some of the values here and the values that individuals, teachers or groups using the space have. How do we reconcile that? There might be interest in incorporating these values but not a knowledge of how to do that: like, 'I'm a Peruvian dance group using the space... How am I supposed to address LGBT issues in my class, in a way that is not forced? I don’t feel comfortable with the fact that I don't have the training or vocabulary to do it.' So right now we need to provide support to all our educators. In the case of a couple of people, a couple of groups, we had to ask them to find another space because it is not aligning with where the space is. That is really uncomfortable.

Immigrant Movement International, (2010-Ongoing). Useful Art Association event, in association with the Queens Museum and Creative Time, 2011. Photograph courtesy of Studio Tania Bruguera

This process can be very awkward because there are people long-affiliated and have relationships with people on the Council. Sometimes they are even family members, so it can get very hairy: but we had to make the decision that if we are going to go through this process we had to have an ethos that we can apply across the board. There are only so many hours of the day that we can use this space, so how are we going to spend our time?

LR: What are the priorities? It is a question of setting priorities.

PR: Right: what are the ways in which one must be responsible and accountable, as part of a community. IMI Corona isn’t just a rental space for rehearsals.

LR: And there is a fundamental agenda: there always has been. So how are you seeing the relationship between the early days, when the international, global questions were front and centre, and the evolution of the space to incorporate the values and criteria being used by the Consejo currently. Globalisation is not news, but the international or cross-border relationships that people have in Queens are of a different quality. I have been searching for the right term for this because it is not global or international it is something else that encompasses very personal connections to other locations, via family and friends and history. In this context, the international relationship isn’t based on capital and the exchange of capital, and so that is sort of a unique flavour that I think predicts also the way that people interact with the big picture question. It is very personal, which makes it not just a political issue.

PR: There is a connection to the places that migrants come from that is very direct manifested in direct support to families or communities elsewhere, for instance. They are building projects abroad, they are starting organisations here. Then I think the interesting thing about connecting to a place like IMI Corona for them is that there is something else beyond this little circuit that is coming in as information or resource or just expanding their thinking, like proposing, ‘oh okay well I might be from this little town in Ecuador and this person might be from a little town in Puebla but we have some similarities, we have some differences, we have ways in which we are trying to preserve our culture here that need to be challenged’. And so there are similarities about the things that they are confronting, but also great differences. I think there is an interesting way in which we are trying to figure out how to support the way that they are thinking about or approach these circuits.

So, for example, if you have built up an Ecuadorian folk dance tradition that is very much about transmission of this information and learning it from a particular source, how do we challenge some of the more patriarchal elements of that tradition without not throwing the baby out with the bathwater, acknowledging the fact that there is a lot of knowledge and wisdom there? One of the ways that we are addressing this is by doing a dance residency with the Peruvian, Mexican, and Ecuadorian groups who are all working with the same dancer. This dancer is second generation Peruvian, who studied traditional Peruvian dance, is also half Puerto Rican - with that Caribbean history - and is a contemporary dancer working in New York. Together they are thinking through questions of identity, generation, and style.

LR: And they are doing this through their own culturally specific lens, looking at where the intersections might be as migrants…

PR: ...and together in the sense of what are they facing as immigrants, and the limitations and politics and competition amongst the various folk groups, and how each stand out, and how their values differ or run parallel.

Immigrant Movement International (2010-ongoing). The monument quilt project to fight rape culture: IMI members in collaboration with FORCE artists and the Queens Museum, 2014. Photo courtesy of the Queens Museum.

The other dynamic is an acknowledgement that there is a lot of political context in the United States or internationally that they don’t really feel like they have access to or understand. In fact, as the Black Lives Matter movement emerged here in the United States, a lot of folks at IMI Corona were asking about the meaning of this movement. What they were getting via Spanish lanugage media (some of which is quite conservative) was incomplete, and whilst racism (and its history) within their own countries exists, it is very different to African-American racism. So really understanding where this trauma was located, how relationships with the police is also fraught, but different. The Consejo decided that they wanted to spend a year really understanding its context and what it might mean to be in solidarity with it. So: how do we as a Museum become the conduit for them to do that, through working with artists that are either Afra-Latino or African-American. Understanding is happening through art-making, collaboration and meeting other organisations: getting a sense of what Black Lives Matter means and in what way IMI Corona might be part of that.

So both of those things are interesting to me, and feel very much like they are international but in a very different way than Tania would propose to be thinking about the immigrant crisis as an international crisis. It had very much to do with IMI Corona as individuals.

LR: It is very personal. This is what I was trying to get at: there is something about this hyper-localism that is extremely personal but also profoundly related to these really big questions and issues, that is - for example - a very different approach to sending a message to the United Nations. These are very different strategies, but I think what is interesting about the way that IMI Corona is evolving is that I could foresee a moment where there is a desire to have an impact in this 'international' space. In fact, we have been talking more and more about language justice and engagement, and how to use the Museum as a platform for civic engagement that can reach a larger community of people.

There are all kinds of different registers that people need to be working on if the change goals are to be realised. This one is very fundamental. IMI Corona is made up of self-selected members of a community who have identified themselves by saying ‘hey I want to be involved in this quite radical project’. This group, while members change along the way, move through several years of work, coming out a couple of years later with not only the popular education model of thinking but also asking what Black Lives Matter means, and how it might be responded to, seems to be a very important political-cultural moment.

PR: Another priority the Consejo has focused on relates to the diversity of Queens. While there are very many different immigrant groups in Queens, IMI Corona is very focused on is Spanish speaking immigrants in our neighbourhood. So another thing this year has been to ask: how do we create relationships with other immigrant groups who speak different languages? How can we learn from them? So we have embarked on a collaboration with another local organisation called Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), who organise South Asian immigrants who are already multi-lingual and multinational themselves. We have also been working with Caracol, which is an interpretation and translation co-operative. Underpinning these collaborations is the attempt to stage series of encounters between members of these various organisation, because often times what happens is that their multilingual leaders talk to each other to work on strategy, but the members never actually connect. So it was really interesting to bring a group of folks from IMI Corona over to DRUM - which is 14 years old now - to have the members chairing a meeting about where their organisation is at, and how they came to it, and to see some of the similarities but also to see that IMI Corona could potentially take this form: if it wants to, which is also a question.

LR: So it sounds like IMI Corona is beginning to work outside the network of its own specific set of skills. And to go back to the point you were making much earlier about social practice and the way that social practice programmes within MFA departments are shifting a bit, I think that is a really interesting piece of the equation. If you are getting social practice students coming from these various fields and they are the ones that are going to become embedded in communities in various ways, their inherent understanding of skills sharing that is needed, and the bridge building you can create by linking different communities that are working towards similar goals but maybe have different contexts.

Global Action on International Migrants Day. D18 march organised by Tania Brugera for first International Migrants Day. December 18, 2011 in Lower Manhattan, where the Migrant Manifesto was read.

PR: For me, it has been interesting that the artists that we have started investing in are now thinking through what more can we do with them. That relationship is a relationship above and beyond an art commission, it is time spent relationship building, and so on. We don’t necessarily know what the next step is but we are always thinking, both the artist and the Consejo, thinking about how can we build on what we have done before.

LR: And I think that speaks to the embeddedness of the project. It is not just about swooping in and swooping out. These are long-term engagements, they are very particular circumstances, there is a lot of trust-building that needs to happen. I think that the depth of that needs to evolve over time, and once you have that kind of relationship you want to keep on building it. As important as it is to also diversify it, there has to be a balance there, and when it is a community effort that is as strong as this one is, it is going to be very clear about who is going to fit and who is not going to fit. There is always that anxiety about introducing something new into the equation and how that is going to play out: because at the end of the day this is a very delicate ecology, even just with the Consejo, never mind the much larger community of folks that use the space and come to the workshops. There is a lot of precarity as well because the Consejo and the community members involved participate in their really precious spare time. They make a space for this in their lives. That brings further pressure on the Queens Museum to respect the process, and nuture it in the tradition of community engagement that we have had here, and to the extent that it is desired. This is always the balance.

PR: The other thing is there is a real connection between the language justice piece and the Consejo’s understandings of themselves as people who can teach and people who are artists. Which is interesting there has always been a kernel of that, that everyone has a kernel of the Gramscian ideal of the intellectual and that everyone is an intellectual and that everyone could be an artist not necessarily all in the same way. But it is interesting to see how many of those people perceive their own work as artistic work. So then there is this other piece that is not social practice students and is not community artists, it is the community as artists themselves who perceive having arts experiences and participating, having art woven through their activism and their everyday lives as a right. The same way that language interpretation is a right. It is actually kind of radical in a way. These aren’t things that people have been taught to say they deserved and expected and could demand.

So to me, I feel like if I could point to a success or something about what this process has done for the community in which the project is situated, it is that is has seated this value system that exceeds the space of IMI Corona or the Queens Museum. It creates a space for community members to say, ‘I am going to go to school Parent Teacher Association and ask why is this piece of text is not translated’. This creates an environment around themselves. Or some organisation might invite them to go to a rally or a demonstration and they will have a list of questions around interpretation and what are the terms, what are the objectives – having that sense of agency around the idea that their participation is going to be framed and respected in a particular way. That is really encouraging to me, and it is something that teaches us about the difference between our initial attempts at providing translation and interpretation to what really happen when you invest more in developing dialogues or spaces for dialogues that are more seamless – spaces where people can really participate.

LR: These are questions of radical participation. I see this in the questions the Consejo asked me – particularly the complex questions about the Queens Museum’s relationship to IMI Cornoa, because it is important not only to be transparent about it but it is also essential for our relationship that this be part of the dialogue.

PR: Yes, and every step is challenging. Thinking about principles of inclusion and making them real is a long, long process that an institution engages in because it’s the right thing to do and is never going to be perfect.

LR: The key is that there must be intention put towards actually making it work, and making it work better. It’s not going to be perfect but it has to be improving all the time: because if are not maintaining those values of inclusion in a bigger sense then you are not walking the walk, especially for a place like Queens Museum.

PR: The interesting thing is what are we learning from each other and how are our activities build upon each other. We are building towards something.

Download this article as PDF

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy

Laura Raicovich is President and Executive Director of the Queens Museum, New York, where she directs all aspects of the Museum’s activities and is charged with envisioning its future. She is a champion of socially engaged art practices that address the most pressing social, political and ecological issues of our times, and has defined her career with artist-driven projects and programmes. Prior to the Queens Museum, Raicovich launched Creative Time’s Global Initiatives, expanding the institution’s international reach. She came to Creative Time following a decade at Dia Art Foundation, where she served as Deputy Director. Previously she worked at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Public Art Fund. She lectures internationally and has contributed regularly to The Brooklyn Rail, and is the author of A Diary of Mysterious Difficulties, a book based on Viagra and Cialis spam, recently published by Publication Studio.

Prerana Reddy is currently the Director of Public Events at the Queens Museum of Art, where in addition to organizing their screenings, performances, discussions, and community-based collaborative programs and exhibits both on- and offsite, she developed an intensive arts and; social justice program for immigrant youth as well as a community development initiative for Corona, Queens residents, many of whom are new immigrants with mixed status families and limited English language proficiency. She has also curated “Fatal Love”, an exhibition of South Asian American Contemporary Art as well commissioned two editions of Corona Plaza: Center of Everywhere,” Queens Museum’s socially-interactive public art projects.

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon