Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips

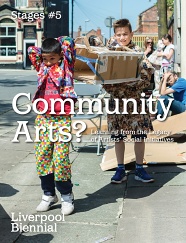

Community Arts? conference, Black-E, Liverpool Biennial, 2015. Photo by Charlotte Horn.

The conference Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Initiatives took place in November 2015. It sought to position ongoing and historical projects made by artists with and alongside communities in the context of contemporary social engagement discourse. In developing the conference, Sally Tallant, myself and our co-workers at Liverpool Biennial and the Black-E, Liverpool, wished to address an endemic problem within the arts which is enabled by three things in particular: firstly, the post-relational aesthetics reinvention of subject-object connections within the arts under the terms of new forms of utopian communicability rendered both investable, collectable and fashionable; secondly, the desperate enforcement of participatory practices by funding bodies under pressure to justify in governmentalised terms their spend on the otherwise elite arts in the UK context; and, thirdly, the erasure of the term ‘community’ within artistic, art theoretical and more general discourse and practice over the past 20 years. We recognise that there are many practitioners – some of whom were able to join us for the event – who recognise and continue to practice within this composite problem. We also mark the strong affiliation with feminist struggles, anti-racist campaigns and demands for intersectional recognition and acceptance that the Community Arts movement in the UK supported, drew inspiration from and continues to struggle within today.

The institutionalisation of participation and engagement is now endemic within the structure of and financial organisation of arts institutions. Across the world, museums, galleries and biennials invite artists or handle artistic initiatives for the purpose of shaping their publics into temporary, qualifiable and quantifiable community. The banalisation of community is pervasive within the cultural industries in the UK as elsewhere – a banalisation rendered complete through the hegemony of that which Wendy Brown recognises as the governmentalisation of ‘good practice’ within the structure of the arts[1]. A banalisation, qualification and quantification demanded by state funding agencies and, increasingly, private patrons.

At the heart of this banalisation – which must be understood as a political investment – is the misrecognition of the subject of its intent – the participant. Here social engagement in the arts not only fulfils private and public criteria of inclusion (remember the shift from exclusion to inclusion in mainstream British rhetoric?) but also maintains – does not disrupt at all – the modes through which the person – the participant-subject – is utilised within a scheme that is entirely wrought through European histories of benevolent liberal governmentalisation. As Isabell Lorey says, '”Western man” has to learn to have a body that is not dependent on particular conditions of existence, which means he must learn that “his” precariousness assumes different extents that he can influence. […] Through attending to what is one’s own, the ties to others are dissolved, relational difference is segmented. Individualisation is the precondition for the Western liberal governing of everyone’s body and self'[2]. Perhaps most frightening is the export of this model at a global scale as increasingly states take up the discourse and practice of participation in the spread of cultural industrial models for the purposes of city branding and neo-financial practices of community investment.

This market relation needs to be examined carefully, for it is the practice that renders Community Arts a brand and branch of liberalism, despite the criticisms of its participant-makers. Our understanding of the Community Arts movement is the exact and angry opposite of this.

What is another rendering of community? Those people that live and work alongside us, physically and virtually. Those people who we affiliate with in different ways, as well as those people we find difficult, have different experiences and lives to us.

Community – rendered explicit and political by writers such as Judith Butler and Silvia Federici – includes our own bodies, whether we be artists, curators, museum directors or other workers, in the development of forms of cultural facilitation. Community includes the fight for local schools, local housing, as well as global justice. This understanding of community – one that has been apprehended across decades by many uncelebrated practitioners – is a direct critique of cultural entrepreneurial community, fashioned in eventual forms of celebration in hierarchies of anticipation and reception.

But community – and here is the configuration that was troubling for our conference – is both a permanent and a transient concept. We know that communities are historically produced (indeed many Community Arts projects were and are founded on the rights of such communities, especially when they are threatened). We also know and experience communities that form around sites and issues, matters of concern, then dissipate. We know that communities are often the strength of temporary agency formation. Yet the contradiction – often conflictual – between temporary and more stable concepts of community comes to be questioned (made questionable) when the facilitation of temporary community is done by artists and arts institutions, through artistic intervention that is misunderstood in inception by parties both within and without, misaligned, ignored, antagonised or otherwise rendered misleading in forms of artistic, curatorial and institutional intervention.

We can say that Community Arts – and specifically the Community Arts movement of the 1970s and 1980s in the UK – sits at the site of this uncomfortable facilitation. Importantly – and missing from many contemporary practices of relational and so-called engaged artistic and curatorial initiatives – is the deep and careful understanding of the power and autonomy embedded in facilitation itself. I have politically foundational, exhilarating and uncomfortable memories of working in Community Arts in the late 1980s and early 1990s, at The Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, with The Theatre of Public Works, with writers and theatre-makers Ewan Forster and Chris Heighes. However researched and connected, I was always to some extent working as a privileged visitor to the site of others (a poor Devon ex-fishing community, a traveller's site under the Hammersmith flyover, in the Peak Freans Biscuit Factory, Bermondsey, for example). Working across huge cultural divides. Working in solidarity. Learning to be wrong a lot of the time.

The Community Arts practices that we discussed at the conference were not and are not glamorous and they are not invested in the accrual of cultural capital, though must now learn the game to survive. We were privileged and delighted to be joined by practitioners who work with the difficulties – the necessary conflicts - of community work. People whose practices are long term investments in sites of political and social struggle, whose focus is less on the production of aesthetic outcomes (although their processes are always driven by the skills and tools of artistic and curatorial making) than on the care for the ecologies of celebration, commemoration, demand and desire of those people with whom they form often long term alliances – those people including ourselves.

Videos: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Initiatives

[1] Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015), p.13.

[2] Isabell Lorey, State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious (London: Verso, 2015), pp. 25-6.

Download this article as PDF

Andrea Phillips

Andrea Phillips is PARSE Professor of Art and Head of Research at the Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg. Andrea lectures and writes about the economic and social construction of publics within contemporary art, the manipulation of forms of participation and the potential of forms of political, architectural and social reorganisation within artistic and curatorial culture. Recent publications include: ‘In Service: art, value, merit and the making of publics’ in Public Servants (MIT/New Museum, 2015); 'Making the Public' in (ed.) Robin Mackay, When Site Lost the Plot (Urbanomic, 2015); 'Contemporary Art and Transactional Behaviour' (with A Wheatley and A McGuiness) in (eds.) Gilane Tawadros and Russell Martin, The New Economy of Art (DACS, 2014); 'Remaking the Arts Centre' in (ed.) Binna Choi, Cluster: Other Cultural Offers (CASCO, 2014); and 'Art as Property' in (ed.) A. Dimitrakaki, Economy: Art and the Subject after Postmodernism (Liverpool University Press, 2015).

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon