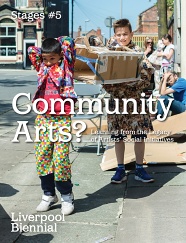

Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas

Ania Bas, PX Story (inside), Commissioned by Yorkshire Artsapce, 2014. Image by Article Works

Ania Bas, PX Story (inside), Commissioned by Yorkshire Artsapce, 2014. Image by Article Works

I perceive the starting point of Community Arts practice to be very different from that of modern-day socially engaged practice. It seems to me that what happened in the 1970s was generated without or outside of institutions. People coming together formed organisations rather than institutions, to make something happen or to tackle issues, often local ones. There were different models, but I have been more exposed to the Jubilee Arts model of being settled and embedded in one place, and occasionally venturing out to local areas or abroad where the same issues recurred and the practitioners felt that they could be part of that conversation.

A lot of work I make is distinctly connected to an institution or commissioner, which implies power dynamics, or power structure. To whom am I accountable? Who is the project manager? Who holds the purse strings? There can be interesting tensions, including with the people I am working with and who can be framed in different terms: participants or collaborators. This relates to the issue of ownership, which for me is an important notion in the context of this conversation. Who is the author? Who is ultimately responsible? Within the Community Arts movement, authorship was more diffused due to the tendency to work collectively. Today, institutions often put pressure on the artist to attach their name to a project. Who is the artist that is engaging the community? This is almost the first thing you learn about a project, even when the project is framed under a collective voice, but institutions tend to silence that voice. Of course there is sometimes a need for anonymity and certain collaborators choose not to have their name made visible because they worry about the consequences of publicly voicing opinions. When I worked on PX Story (commissioned by Yorkshire Artspace in Sheffield in 2012) I wanted to name everyone I had been collaborating with but then I was challenged by one of the participants who said in her contribution to the book that I had to take responsibility for it. ‘You made it happen, now you need to take credit for it in case any of the content creates upset’. I had imagined the authorship to be shared, but the book ended up having just my name on the cover as the convener of voices.

Returning to the tensions of being a commissioned artist, the contract is often the sticking point. You first have conversations about what’s possible for the project and its production, and then comes the time to sign the contract – usually quite late in the day when work is already under way – which relates to the process in extremely stiff terms. Recently, I had to sign a contract that stipulated that the work could not in any way be of a political nature. That happened half way through, so what to do? Do I refuse to sign it and still complete the project? Do I stop the project? Do I consult the people I work with and we decide collectively what this contract means for the integrity of the project?

Ania Bas, PX Story, Commissioned by Yorkshire Artspace, 2014. Image by Article Works.

Ania Bas, PX Story, Commissioned by Yorkshire Artspace, 2014. Image by Article Works.

You asked me to reflect on the position of the outsider or newcomer. I do see the value of being a middle person, someone who is interested in conveying, for example, the history of a locality they do not belong to. The newcomer may bring a fresh and sharp outlook on a given situation without emotional baggage or connection. Being external may give you the advantage of not being caught up in some inner tension, for instance why certain people on the block wouldn’t talk to one another. People stick to historic reasons, however recent they are, and someone like me can question that and perhaps help shift attitudes. At least there is the potential.

To return to the original point about the difference between Community Arts and socially engaged practice I think of the former as activist practice – activism being the prime element that drives people to do their work. I would not call myself an activist. I do look for appreciation in the arts rather than elsewhere and identify art as my field of operation. Some might say that the work I have been doing with the Tower Hamlets Artist Teacher Network is activist work. I’m more interested in the situation when a group of people, as it is the case with the arts teachers, come together and realise they have strength and that they don’t need to accept everything that is proposed and delivered to them by, for example, the gallery sector. Public galleries wish to work with schools but tend to impose their agendas on teachers and I’m interested in how the art teachers can negotiate these conditions and work on projects they are also interested in. I don’t think it’s activism but rather about building strength.

Recently a collective, that I am part of, has been commissioned to work on a new work and for the first time we have had conversations with institutions that didn’t see this project in the service of their current programme or utilised it to enhance their public engagement strategy. The fact they saw it as an artwork instead was a significant step for me.

Workers report January/February ’79, Jubilee Arts Archive, 1979. Photo: Ania Bas

Workers report January/February ’79, Jubilee Arts Archive, 1979. Photo: Ania Bas

‘Workers Reports’ are testimonies from Jubilee Arts employees prepared most probably for board meetings. Ania Bas was one of the artists working on the Jubilee Arts Archive project in 2014 and found three separate reports, amongst other documents, which revealed the challenges facing the community artist of the time.

Founded in 1974, Jubilee Arts was a community arts organisation based in the metropolitan borough of Sandwell in the West Midlands. The Jubilee Arts Archive 1974-94 contains a substantial collection of negatives and slides – over 20,000 – conserved by Sandwell Community History and Archives Service along with standard 8 film, VHS video and miscellaneous print materials. The photographs were taken primarily as documentation of their projects in Sandwell and the Black Country - and sometimes further afield. They were made by both professional and amateur photographers as well as communities.

Download this article as PDF

Ania Bas

Ania Bas is an artist and through her practice she creates situations that support dialogue, exchange, and explore frameworks of participation. She is interested in the ways that narratives shape understanding, mythology and knowledge of places and people. Her work is presented through texts, fiction, events, walks, performances, useful object and publications. She is a co-funder of The Walking Reading Group (2013-16) and was an Open School East associate (2013-14). Her artworks have been commission by the New Art Gallery, Walsall (2009), Whitechapel Gallery, London (2010), Yorkshire Artspace, Sheffield (2012), Radar, Loughborough (2105). Currently she works with PEER gallery in London developing a new local audiences programme. www.aniabas.com

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon