Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman

'Heroes Wall & Wild West Wall' Marlon Brown, West Dulwich Station, 2011. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

'Heroes Wall & Wild West Wall' Marlon Brown, West Dulwich Station, 2011. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

I probably have quite a bit in common with Emily Pringle in terms of my relationship with the field of community art practice because we both worked in the field of gallery education and of pedagogical practices being initiated through galleries. What’s interesting and complex about it is that the historical roots of these practices in galleries are very much connected to threads of community art practice that was largely self-organised and connected more specifically to artists’ practices within community groups. I suppose one slightly negative take on it is that when galleries started to set up education posts, some of these people who occupied these positions (largely practitioners themselves) became at some point co-opted into institutional practice and public funding streams.

I think of my work and my approach to curating in very political terms so it’s always felt very important for me to track back into the trajectory of artist-initiated and community-led art practices as a way of reflecting on the meaning of what I have been doing within galleries. Before working for Create, I worked at the Whitechapel Gallery where I commissioned a number of projects including Reclaim the Mural, which lasted almost three years. It was with a group of artists – Benedict Drew, Emma Hart, Dai Jenkins, Dean Kenning and Corinna Till – who together set up a project that asked whether it was relevant and appropriate to make a mural today. It gave them, me and the Whitechapel Gallery a springboard to explore the legacy of the London mural movement and to understand how the Whitechapel Gallery as an institution was connected to that history; what the motivation were for the artists who were trailblazing that movement in the 1970s and 1980s; how it was all funded and what role funding had in creating that movement.

'The Battle of Cable Street' Dave Binnington, Desmond Rochfort, Paul Butler and Ray Walker, St George's Town Hall, Cable Street, 1983. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

We organised some events that brought together some of the original mural artists to come and engage in a discussion about these experiences with artists practicing today, who potentially associate with the notion of the socially engaged art practice. What was interesting was how difficult it was for that earlier generation of artists to engage in this conversation – there were coming at their practices from such different places. The mural artists had varying commitments but at the heart was a desire to politically challenge the art school and the gallery systems – a lot of them had come out of painting at the Royal College of Art. Their second commitment was to mobilise communities to articulate their needs and to use art as a way to take control of their political circumstances. As for the younger generation of artists, who were deeply inspired and curious about the original movement, they were reacting politically with reference back into the art world and the political nature of the art world itself.

'The Vision of Angels' Stan Peskett, Goose Green, East Dulwich, 1993. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

The gulf between these two generations and types of practitioners quickly grew and the mural artists got really exasperated with the younger artists. The former would say: ‘What we did was all about action, we were trying to change the world, and you lot sit around talking about theory and ideas. Nothing you do is going to result in change. ‘But from the younger generation’s point of view, action without thought and action without theory is dangerous and risks generalising and essentialising communities. What the younger generation was engaged in was a very reflexive practice. If you read between the lines, you realised that some of the original mural painters had been actually fairly reactionary about some of the radical approaches to artmaking and objecthood in the 1970s and 1980s; they had for instance strongly reacted against video art and conceptual art. What’s really dynamic and interesting for me is the strands that connect the art world and arts practice that’s framed within the terms of community, as well as the deep divisions between the two.

'Poplar Rates Rebellion Mural' Mark Francis, Hale St, Poplar, 1985. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

There was a point at the Whitechapel when the two were particularly successfully connected, at least from my perspective. Back in the 1980s there was a man named Martin Rewcastle who was working as the education programmer. He was doing quite dynamic things in the gallery that would be very difficult to achieve now, and the reason for that was he wasn’t called a curator and he didn’t connect himself to the trajectory of exhibition making or art history. Instead he aligned himself much more closely with notions of community development and teaching. He invited local artist groups and muralists to take over all of the spaces and to set up artist-run printmaking studios, poster workshops, and all the things we associate with the Community Arts movement. From what I could glean from the archive, he did it in a very ad hoc and unchoreographed way. There wasn’t much thought put into the way it was presented within the space, instead all of the emphasis was about disturbing expectations about who was able to express their expertise within the gallery. It would be impossible for this to happen in the same way today; if it did it would come through a curatorial lineage and I suppose the closest the Whitechapel has come to that was with the exhibition The Spirit of Utopia in 2013. Some of the projects successfully activated the gallery and engaged viewers’ participation, and the space was treated with careful curatorial consideration, but unfortunately what it did lack was any echo of practices operating outside the art world, and beyond the walls of the institution.

'The Battle of Cable Street' Dave Binnington, Desmond Rochfort, Paul Butler and Ray Walker, St George's Town Hall, Cable Street. 1983. Photo courtesy of Marijke Steedman.

On a very different, yet crucial note, the conversation on race in the Community Arts movement shouldn’t be overlooked. There are many ways of approaching it and I will do it here through Grant Kester’s book Conversation Pieces, which makes an interesting but complex point about class as well as race relations. He talks about the existence of an index of authenticity in the evaluation and critique of a Community Arts project. For instance, the value and integrity of a project would increase the closer it got to what was deemed authentic, i.e. dealing with ‘real people’ and their ‘real lives’. And the greater the social differences between the artist working with the community and the community itself, the larger acclaim given to the project. If we take the example of a white artist coming to work with Bengali communities, the degree to which that artist manages to create meaningful relationships with these communities is the scale on which the success of the project is measured. This is obviously deeply problematic and cynical, and in the 1980s and 1990s there was a clear missionary zeal about working with multicultural communities without a voice in the art world.

Download this article as PDF

Marijke Steedman

Marijke Steedman is the Curator for Create. She has a particular interest in the systems that influence how art is produced and paid for such as formal education, town planning and the role of local authorities. Previously she developed the Community Programme at Whitechapel Gallery, and before that worked at Tate Britain. She has worked closely with many artists including Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Nedko Solakov, Jens Haaning, Emma Hart, and Matt Stokes and has worked with writers including Lars Bang Larsen and Grant Kester. She edited the Whitechapel Gallery publications Gallery as Community: Art, Education and Politics and Reclaim the Mural.

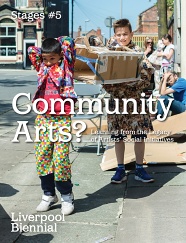

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon