Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Action Space (created in London in 1968 and renamed Action Space Mobile in 1981) was my main introduction to the history of Community Arts practice in the UK. Many generations of practitioners congregated around the millieu of Action Space, including performance artists Ken Turner, Roland Miller, Anne Bean, Mine Kaylan, Rob La Frenais, who is now curator at The Arts Catalyst, and Mary Turner, one of the founders who has the group's archive and has written a book about it. For me and my fellow artists Anna Best and Ella Gibbs, who introduced me to ex-members of Action Space, these were important influences, or at least I can say that I could recognise in their work some of the same impulses and convictions that move me.

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

I've always felt like an outsider in that conversation about community grassroots art versus socially engaged practice, because I don't identify with either. In terms of who is entitled to work on a specific project, history or community, I always do things out of my own position and interests, and that's why for me not being commissioned is important. I don't want to do the work for anybody, I want to follow my interests and conviction and I have found that when I do that and I am clear about my intentions, these issues are not a problem. For me, and I follow the conceptualisation of both Sophie Hope and Judith Stewart on that, the commissioning factor is what defines socially engaged practice and how it gets articulated within the art world. And community art has also partaken in the commissioning circuit, perhaps commissioned by different bodies, but public funds have gone into it too.

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Democracy Collaborative project initiated by Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre, Uruguay, 2015. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

In 2006, I initiated the project Do you remember Olive Morris?, which revisited the figure, actions and affiliations of the British Black feminist activist Olive Morris (1952-79). Two years later, the arts organisation Gasworks got involved and in retrospect, it became an issue, because even when it wasn't a commissioner, it somehow ended up playing that role. I try to avoid the idea of the project or the commission because then you are almost contractually obliged to carry it through. Also, if you get rid of the idea of the project, you get rid of the time pressure, and time is a big concern of mine. With the Olive Morris project, for me the last part – the exhibition at Gasworks and the publication – was the least enjoyable and rich because it was about holding all things in balance; there was a lot of pressure and politically I was uncomfortable at times. I had to keep everyone on board and satisfied, managing expectations; it was exhausting. There was, for instance, a conflict between the time that the Remembering Olive Collective needed to discuss the events, and the print deadlines to announce the events and make them visible. In a way everything was more manageable until the art institution came on board, as I suddenly became the lead artist and that raised questions about authorship which weren't present before. This sense of property that artists and institutions sometimes have over ideas is unhealthy and uninteresting to me. For me the most remarkable thing about this project is to see how women, including myself, were transformed through the whole process, to see how it has changed our lives and the way we behave and act politically in the world, as women, as artists, as activists, as academics.

Presentation by Migrantas Collective at Remembering of Olive Collective event, Do you remember Olive Morris, Gassworks, 2009. Photo: Jessica Mustachi.

Presentation by Migrantas Collective at Remembering of Olive Collective event, Do you remember Olive Morris, Gassworks, 2009. Photo: Jessica Mustachi.

I view art as an incredible space to do things out of the grid, but my main interest in life is political, militant. I'm not interested in having a career as an artist or in becoming famous. Of course I appreciate recognition and hearing from someone I respect, that what I do means something to them. I also use my institutional credentials to get some of the things I want and need to carry out my work. I am not against that, but it's not what motivates me. When you move on the terrain of community or activism, your credentials are: who you are, what you've done, how long you've been doing it for, how well you know your politics, and how you're going to be able to sustain your position.

Remembering of Olive Collective members at AGM 2010. Do you remember Olive Morris, Gassworks, 2010. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Remembering of Olive Collective members at AGM 2010. Do you remember Olive Morris, Gassworks, 2010. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

I'm from the 1980s, I'm more of a punk. I'm not going to change the world in a messiah-like way and I don't need institutional validation, unlike the generation who were active in the 1960s and the 1970s. They now want credit for what they failed to achieve because at the time they chose certain things over others; for me there is a contradiction in being against the art system back then, and now wanting the same system to give them their dues. By the same means they are dismissing and silencing what the younger generations do, just because they have a more pragmatic or collaborative approach to institutions. Up until the 1950s (and even later in Uruguay) the Communist Party was very influential in the way people, a decade later, thought about tactics of organising. To me the talk of horizontality that was prominent at the time was all fake, the way people organised was brutal, it was incredibly pyramidal and patriarchal, and women had little agency. After punk, a different mindset started to seep through, the true culture of the working class, something closer to what Raymond Williams points to when he talks about a“common culture”[1]. I think even when in the 1960s and 1970s the working class was active in the social struggles, the forms were designed with a middle class mindset and under the intellectual leadership of middle class marxists. The 1980s youth culture brought a different kind of sensibility, in which you were nothing without the collective, we were not interested in leadership or in winning over power, just in creating spaces where we could just be the way we wanted to be. At least this is my perspective and experience growing up in Uruguay, in a working class family not involved in party politics. In my family it was always made clear to us that you only achieved things through the support that you got from others, and you duty was to do the same; you as an individual were not that important, someone else was always in more need than you. And that has had a huge impact on my practice, this is what solidarity and working class culture mean to me, to this day.

Remembering of Olive Collective members Shiela Ruiz and Altair Roelants. Feminist Library, (London), 2010. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Remembering of Olive Collective members Shiela Ruiz and Altair Roelants. Feminist Library, (London), 2010. Photo courtesy of Ana Laura Lopéz de la Torre.

Through the process of writing my PhD, I came across a couple of artists who would not be considered part of a canonical history of socially engaged or community art, but what they did was really close to what I try to do as an artist. One is Guillermo Vitale (1907-92), an amateur mosaic artist from Montevideo who was essentially a neighbour making public art and using his work as a vehicle to bear witness of the struggles and achievement of his community. The other one is Benito Quinquela Martín (1890-1977), an Argentinian artist, who also transformed his neighbourhood of La Boca. He was a leading figure of the figurative painting movement in Argentina, in fact he was a best-selling painter throughout his life. He used his proceeds to fund the part of his practice that involved developing traditions, institutions and the identity of his neighbourhood. This made me realise that the technical means or media is not what matters, it doesn't matter if you are a conceptual artist or a mosaic artist. It is about your focus, your commitment, where that sits. I also realised something quite simple but important about participation: in the art world we try to generate opportunities for people to participate in something we have created but I think what I'd rather do is participate in what is already going on. The contribution and the sense of my work come from that realisation. In order to achieve the things that I aspire to politically, I have to participate in the life of communities I am part of, with my artist's mind as an equal to others with different skills and mindsets, and not as a facilitator, a convener or a manager of others’ creativity.

[1] Williams, Raymond. Culture and Society 1780 - 1950. 1958. London: Penguin, 1985.

Download this article as PDF

Ana Laura López de la Torre

Artist and director of Centro Cultural Florencio Sánchez in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Ana Laura López de la Torre is an artist, writer and educator. Her practice is involved with ideas of the “common good”, both in terms of what is already common to people – what we are compelled to share, for example a public space – and of what else we might be able to share voluntarily through generosity, collaboration and exchange, by pooling resources and producing communal knowledges. She is the Director of the Centro Cultural Florencio Sánchez, a municipal cultural centre in Cerro, a historical neighbourhood in the periphery of Montevideo. She have realised projects for organisations including the Whitechapel Gallery, Gasworks, Tate Modern, Tate Britain, South London Gallery (UK); La Casa Encendida (Spain); Demokratische Kunstwochen (Switzerland); 9th Mercosol Biennial (Porto Alegre, Brazil).

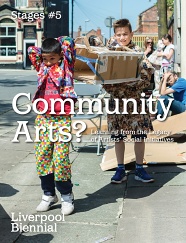

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon