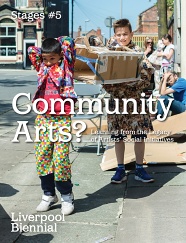

Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle

My interest in Community Arts practice started out when I was at art school in Wimbledon in the late 1980s, early 1990s. It was very traditional, I was in the painting department, making work in my studio, and at the end of it all the aspiration was to find a studio and have shows. However, one of the tutors at Wimbledon was the artist Richard Layzell, who worked in community settings. I got really interested in what he was doing; it made sense to me that you could do a practice with people, rather than in the isolation of a studio. I come from a family of teachers and at the time I was thinking about how to be involved in education without becoming a teacher, which I didn’t want to be. There was a scheme run by the Arts Council, which was about training artists to work in an educational context through a funded short course, so I did that. Then I started working as an artist doing residencies in schools. At the same time I joined a Community Arts organisation called the Southwark Arts Forum in the early 1990s and worked with them on an off for five years; it was all voluntary.

Southwark Arts Forum was a really interesting model of a locally-rooted organisation. It was about enabling a community to articulate its own culture and giving voice to people to be able to express themselves and have cultural agency, so very much inspired by the Freirean model. The notion of fine art wasn’t explicit in the discourse, it was much more about a model of cultural democracy as articulated by Owen Kelly. Southwark Arts Forum had been started by artists and was run by artists. It had a grant from Southwark Council and the Arts Council, a paid coordinator who was responsible for fundraising and for keeping the show on the road, and all the rest of us popped in and out, and had individual projects that we might be organising under the auspices of the Forum. I sat on the steering committee, it was all pretty ad hoc, we used to meet monthly and organised various events including an annual carnival in Burgess Park. We also did music and mural painting, and provided support for other artists.There was a sense that the Forum could be a place where people would come, share ideas and find a kind of support network. I wouldn’t say it was as overtly political and activist as some other practices of the time, the Forum was seeing itself more as servicing the community at the tail end of the first wave of the Community Arts movement. It’s very telling it had funding from the Arts Council and the local authority. For some critics of Community Arts practices, Owen Kelly among them, that was the sell-out point; as soon as Community Arts organisations started getting funding from the Arts Council, the whole radical agenda was diluted. And I do remember an awful lot of our committee meetings were about how much funding we needed to raise just to keep the show on the road, rather than what other projects are we going to do.

The tension between Community Arts and fine arts was tangible. There were artists who had their own community-based practice and were involved with the Forum who had a kind of resentment about why the Arts Council didn’t recognise their work as a legitimate form of art practice. It was seen as something different. But this period of Community Arts predated that instrumentalising agenda that came with New Labour: it wasn’t fine art in the service of making people ‘better’. It was about how to support a community to get in touch with creativity and allow that creativity to take form in ways that are authentic to the community. It was also about building long-term relationships with other partners in the borough, against the parachuting model.

I lessened my involvement when I got a job at the Chisenhale Gallery in 1995 and moved away from Community Arts to gallery education, although at the time there was a very close crossover between the two. I would say that gallery education at that stage was informed by a similar ethos to that of Community Arts. In the early days, gallery education was very much about supporting people to come into the gallery space and engage with the art, while enabling them to create their own creative response to it. And to a certain extent, I still think that’s the model that gallery education operates on in this country. I have a particular interest in documenting the history of gallery education because it is a very hidden practice and it’s the same for Community Arts practice, with people working away, sometimes through choice, not wanting a profile but just wanting to do interesting work. But they do rely on funding to do their work, and although it is practitioner-led, it has to have some kind of institutional policy support. I find interesting how artists have learnt how to work with the policy trends, particularly in the 1990s period with the huge instrumentalisation of art practice and gallery education as an arm of the social services without compromising their work. Many artists I know excelled at shifting their language to fit what the funders wanted, but their practice didn’t fundamentally change.

Download this article as PDF

Emily Pringle

Head of Learning Practice and Research, Tate

Emily trained as a painter and worked for many years as an artist, educator and researcher in a range of cultural and community settings in the UK and internationally. She has a particular interest in the role of the artist in education contexts. Her publications include 'The Gallery as a site for Creative Learning' in The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning (2011). She is currently Head of Learning Practice and Research at Tate where she is responsible for strategic programme development and overseeing research and evaluation. She is the editor of the publication ‘Transforming Tate Learning’ (2013) which documents the development of research-led practice across Tate Learning and is the convenor of the Tate Research Centre: Learning (www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/learning-research).

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon