Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read

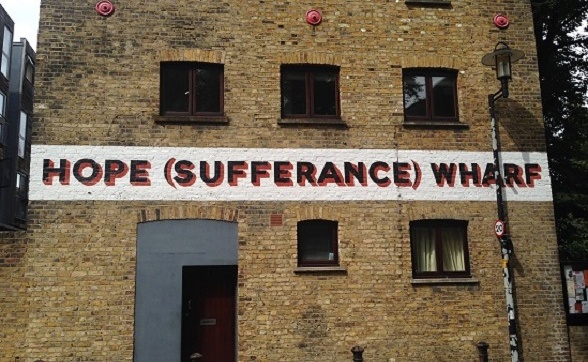

Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop at Hope Wharf, 2001. Photo: Alan Read

I worked in a small pedagogic project during the 1980s called Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, in south east London, alongside a remarkable theatre-maker named David Slater, who has since then been committed to the work of Entelechy Arts in the Lewisham area nearby, in what must count as one of the most inspiring durational performances one might imagine, should duration ever mean what it really says: that is keeping on keeping on. In Rotherhithe I was working amongst a vivacious local dock-side neighbourhood, and a no less vital peer group of theatre and choreographic students from Dartington College of Arts in Devon, who funded the project from its inception in the mid 1970s to its closure in 1991 [1]. We were certainly not alone, Loraine Leeson and others were doing exceptional work in the very same contested area at the time.

London Docklands Development Corporation and Incoming Capital, 1983-2015. Photo: Alan Read

This period spans, almost exactly during the 1980's, the flooding of the Docklands area of South East London where the Workshop was located, with free-market capital driven by the unelected quango, the London Docklands Development Corporation formed in 1981. The LDDC was free from the constraints of democratically empowered local-planning and incentivised by offering massive tax breaks to those multi corporations that were willing to decamp to what was, at the beginning of all this at least, a much-loved yet rather isolated neighbourhood in the bow of the Thames between Tower Bridge and the Royal Docks.

Plant Science, Forster & Heighes, 2013. Photo: Alan Read

Plant Science, Forster & Heighes, 2013. Photo: Alan Read

Amongst those groups, that numbered more than 200 students in all, was Andrea Phillips, (who happened to be one of the convenors of the panel this writing was for), Kevin Finnan, the now Director of Motionhouse who choreographed the opening of the Para-Olympic Games in London, the theatre makers Forster & Heighes whose work features in this quarter’s 20th Century Magazine, Sadie Hennessy the artist and founder of Hutstock, the Booker Prize short-listed novelist Deborah Levy, the curator and previous director of the Green Room, Bush Hartshorn, the performance and award winning filmmakers Desperate Optimists, Michael Hulls the lighting designer, amongst many others. Communitarians all you could say with no presumption as to what kind of community might be at stake.

The Grave of Prince Lee Boo, St Mary’s Church, Rotherhithe, 1995. Photo: Alan Read.

The Grave of Prince Lee Boo, St Mary’s Church, Rotherhithe, 1995. Photo: Alan Read.

And the point was not them of course (though their own pedagogic development was almost by way of a side-bar our responsibility) but those with whom they worked, in their hundreds, making performances, theatre, dance on the street, in schools, in older people’s homes, in council accommodation, in centres for those with disabilities, in the city farm, in the Peak Freans factory site, in the launderette, the hairdressers, the Café Gallery and the park itself. A community of those with nothing, really, but location and some sort of ‘spare time’ in common. And sometimes, over that 16 years, we got to work in our theatre, in a dilapidated warehouse on the river, now split into four ‘luxury’ apartments, the most recent having sold for several million pounds just last year. Well, it does have a splendid river view.

Warehouse Crane, Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, 1983. Photo: Alan Read

Warehouse Crane, Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, 1983. Photo: Alan Read

I am not sure that this kind of commitment is unthinkable today by pedagogic institutions, I am sure there are positive examples represented throughout the UK and beyond, but I think institutions with their beady eye to the bottom line of profit and loss, and both their other eyes trained remorselessly on the consequences of student feedback, might now baulk at the opportunity to unleash their finely tuned cohort onto the vagaries of such untested locations, such erratic publics, such potential for loss as well as gain, such potential for ‘getting lost’ as finding ones way, such potential for disappearances of the unmarked, as distinct to the viable and the visible, such opportunity for laziness in resistance to a work ethic as capitalisable productivity.

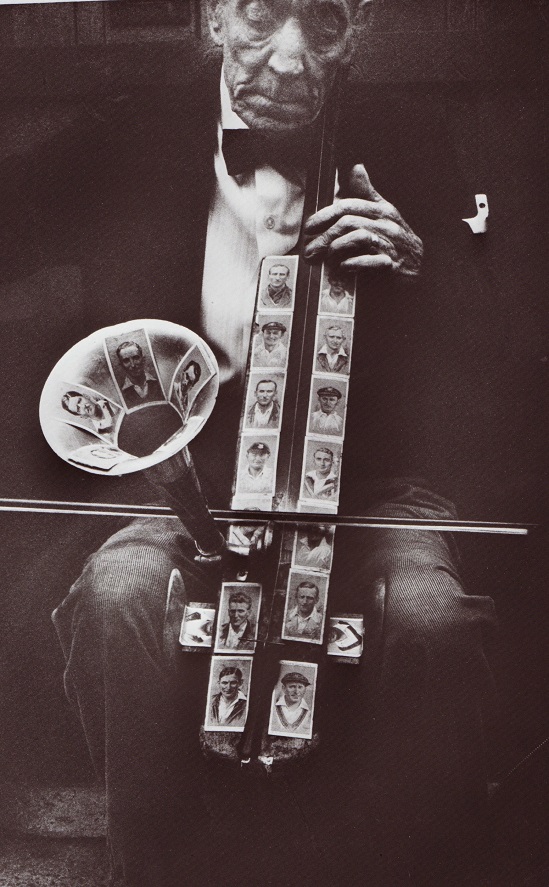

Theatre & Everyday Life (Routledge: London, 1995). Cover Image: Marketa Luskacova.

Theatre & Everyday Life (Routledge: London, 1995). Cover Image: Marketa Luskacova.

There were of course far more of those who we never worked with than we reached, and reflecting now on the gatekeeping of the theatre and its resources by a predominantly white, disenfranchised working class community, I shudder to think how our work made so few inroads towards exploring the largely marginalised and embattled ethnic diversities of the area. I flinch on reading my own prose on this matter in the book Theatre & Everyday Life that I wrote in the years immediately after the closure of Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, where I came up with a counter intuitive concept, Lay Theatre, to describe all those in the commons at odds with professionalism, that I am happy to say was so counter intuitive it was barely ever mentioned again by anyone else, anywhere.

I wrote the book as a ‘less than rapid rebuttal’ to Peter Brook’s romantic work, The Empty Space of 1968, that had started with that resolutely expansionist, if not imperialist line: ‘I can take any space and call it a bare stage’. And I followed up with my own ludicrously portentous line: ‘That is not in question any more than rulers throughout centuries have said, I can take this space and call it my country’. A sentiment that I rather regretted when, some years later, Peter Brook quoted it back to me after a Platform event on the stage of the National Theatre where his space-finder general, Jean Guy Lecat, and I had been musing on the significance of space for theatrical acts. I wasn’t put off writing though as I felt there was some writing to do on these very matters. The question of community that is, which appeared in large measure at the time to have been immune to theory.

There were books available, amongst them Steve Gooch’s useful but slender All Together Now: Community Theatre – An Alternative View (1984), but the vitality of theoretical speculation passed this writing by on the other side as though questions of community were ones best conducted in languages that were as accessible as the principled commitment to access in the arts raging at the time under the broad front of a soft socialism. I thought this a mistake with the whiff of patronage about it as though the avant garde in its minimalist intelligence had the sole right to critical scrutiny while those publicly accessible forms would be necessity consigned to the bin marked utilitarian, ‘welfarian’ you could say. Honourable exceptions here would include Sonja Kuftinek’s later incisive work, Staging America (2005) on such problems in community inflected writing, with particular attention being paid to the work of US company Cornerstone Theatre.

But as the big-gun battalions of socialised theory took off through the 1980s and 1990s (leaping to the social aesthetics of the 2000s) it was as though this community ‘movement’ had never existed so weak its claim to anyone’s theoretical, by which I mean reasoned, critical attention. Despite the fact that Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Judith Butler, through to Nicholas Bourriaud, Claire Bishop and Shannon Jackson were centrally concerned with questions of democracy, precarity, participation and assembly, the kinds of practice gathered and discussed at the Liverpool Biennial event were peculiarly absent as though either precluded from discussion by their plain, banal and often minimal outcomes, or somehow considered off-limits for their pre-intersectional commitments (despite the obvious fact that many of these movements were always and already the inspiring forerunners of everything intersectionality later claimed in attempts to reacquaint identity groupings that theory had worked actively to separate in the first place).

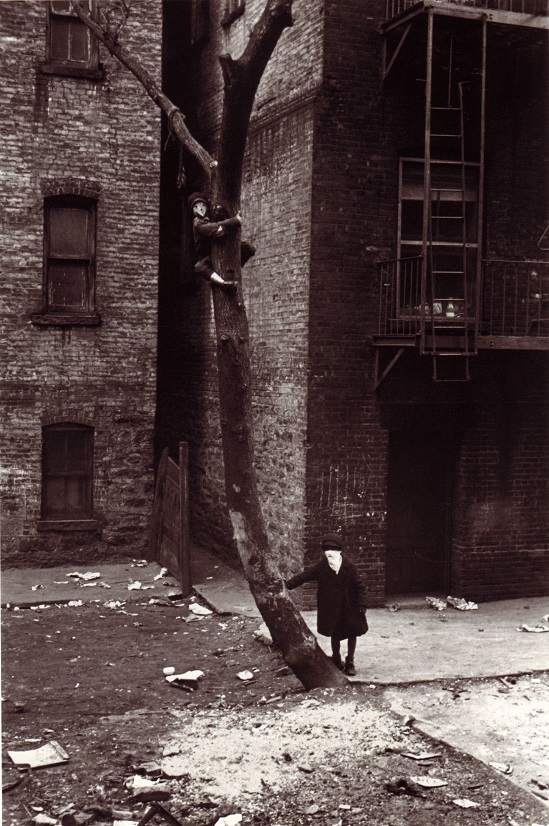

Theatre, Intimacy & Engagement, (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2008). Cover Image: Helen Levitt.

Theatre, Intimacy & Engagement, (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2008). Cover Image: Helen Levitt.

A few years later, Theatre Intimacy and Engagement (2008) was my response to Jerzy Grotowski’s Towards A Poor Theatre, wondering why we aestheticise the minimalist purveyors of poor in art, often practicing their minimalism with the support of a healthy trust fund, when there are quite enough ‘poor’ to be getting on with more materially outside this charmed circle. And, then, more recently, with many of those early experiences still in mind, Theatre in the Expanded Field (2014) is a response to Richard Southern’s magisterial book of 1962, Seven Ages of the Theatre, in which I make some arguments about what ‘radical inclusion’ might look like if we stopped legislating against the inclusion of infants, animals and inorganic things in a largely ego-ridden humanistic theatre. A theatre that, the company at the Liverpool Biennial conference excepted, has largely failed to notice both Goya’s protagonists in his magnificent painting Men Fighting with Sticks, hanging in the Prado Museum in Madrid, are drowning, equally quickly, as they simultaneously sink into the sands being swallowed up by the environment that they presume to be the stage of their conflictual angst.

So, there were in these recent years some people, some practices, and there were some concepts, in the form of books. But what have I learnt?

Before

Well, before intersectionality was given a name, when it was just the very complicated and time-consuming thing that people like David Slater did with each of their days, everyday, before relational aesthetics really got cooked, before participation became the key to engage the precariat, before publics and counter publics were discovered, before criticality, the quotidian, pedestrianism, and immersivity became the watchwords, then something, with some if not all features of these variously described things, was going down, seven days a week, alongside Frances Rifkin at Recreation Ground in the 1970's and then Banner in the 80’s, alongside groups like our neighbours London Bubble and further afield Augusto Boal, Monstrous Regiment and Joint Stock, Freeform and Cultural Partnerships Limited. It was, I think, always considered a ‘broad front’, like the glowering weather, like a meteorology of practices that eddied and flowed alongside others without having, necessarily, to take account of others. Though it was always nice when we did, take account that is. And Francis Rifkin and others were especially good at such accounting. And pre-digital as it all was, it was released from the anxiety of the archive, the fetishisation of the Facebook Time-Line that binds.

From this congruence of practices I have learnt that before can be such a stupid word, and it is obvious as I intone that litany: ‘before relationality’, etc. etc. With all respect to my (ex) historian friends: who really cares what went before? I mean really, when there are pressing social commitments at stake. And those terms are just the death rattle of stupid security, our investment in conceptualisations of things that we know deserve better than words that fail the complexity of passions that we have shared and the passions of others now gone. Albert Hunt was one fondly remembered here in Liverpool on a weekend when his spirit floats over the proceedings like a benign force of nature.

After

Before might be a stupid word, but without a fuller sense of the past, the word after can expose stupidity equally well. The theatre history that I have been sketching in here has, as the excellent Liverpool Biennial seeks to problematise, been at best occluded and sometimes elided by more recent histories of apparently related and relational things, that might benefit precisely from tapping this longer history of the coeval, what it means ‘to be’ during others.

During

There is certainly a gaping, yawning, Community Theatre shaped hole right at the heart of Nicolas Bourriaud, Clare Bishop and Shannon Jackson’s excellent work, where it might do some serious irritating of their well-held convictions. To have come about and done one’s work during these things that are recovered, recorded and celebrated in events such as the Liverpool Biennial, relationality and its various bastard brethren, siblings and offspring, might if concepts had any agency, offer us pause for thought. Although I am not at all sure what direction such thought might take given that no one ever anyway deployed the term ‘community’ without the scariest of emboldened scare quotes attached to it.

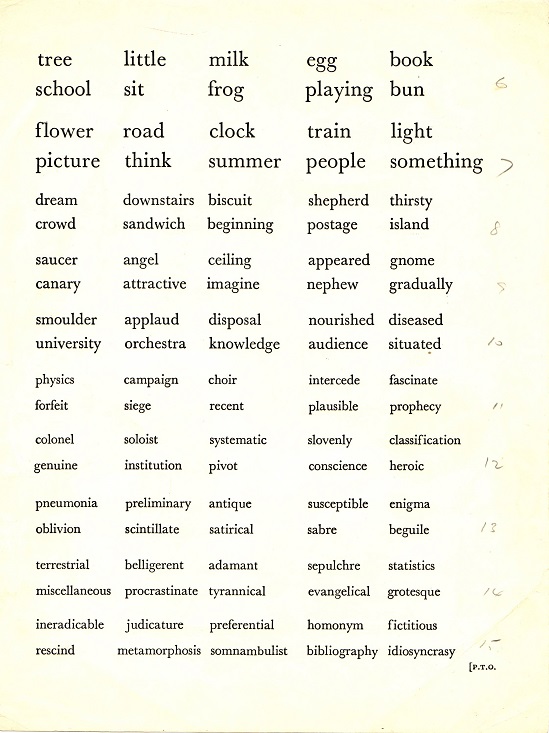

Schonell Reading Test, Alan Read’s School Copy, 1965. Courtesy: Alan Read

Schonell Reading Test, Alan Read’s School Copy, 1965. Courtesy: Alan Read

But concepts don’t, have agency that is, as I said they are more often than not stupid, and we get what we deserve from them. But unlike the philosopher John Ó Maoilearca who proposes All Thoughts are Equal (2015) in his lovely new book, I do not think all concepts are equally stupid. Unlike terms like ‘In Yer Face Theatre’ that you know (and the fine author knows) is redundant before it has even left your tongue, or Political Theatre, or Community Theatre that fall hopelessly short of our hopes, some concepts strike us, now and again, as prescient, persuasive and even sustainable for more than the few examples offered, before we realise that all exemplary cases are exceptional by their very nature. My examples are not yours but this does not mean we cannot share and expand our vocabularies of that keeping keeping on, and the absolute necessity to stop whenever continuous delivery begins to do the damage that it does.

Los Angeles River from the Air, 2014. Photo: Lee Barden

Los Angeles River from the Air, 2014. Photo: Lee Barden

And, we need to remain vigilant to the lessons of that ‘keeping on’ wherever we notice it, for those for whom stopping is unthinkable. While I am talking over, enjoying talking yes, but falling prey to that disease of the occasion (such as the platform of a Liverpool Biennial), delivery, I am talking over those such as David Slater who is keeping, keeping-on. And he is not alone, as that ‘keeping, keeping on’ is everywhere we look. I was writing these notes in late 2015 for delivery in December 2015, and The Guardian I was scanning to avoid doing what I was supposed to be doing, carried this picture of the 51 mile-long Los Angeles River. The feature is headlined in such a way as to catch the culturalists’ eye, referencing Frank Gehry and a job to be done, that only Starchitects with their super-powers can apparently do.

But embedded in the feature itself is the modest figure of Lewis MacAdams, a seventy-year-old poet and activist who founded the Friends of Los Angeles River in 1985. So, he has been going at it, as long as I have not. He, that is Lewis MacAdams, has been going at it some time longer than Theaster Gates, whose work seems increasingly problematic at one level of peripatetic cosmopolitan mobility, yet I very much admire it on its more settled and sustained occasions. And Lewis is not best happy. He reminds me of David Slater in some ways when he was at his very best quizzing in continuously critical care those who came and went with the fashion. He is not best happy at the sudden announcement that after forty years of his own activism Frank Gehry has just been put into ‘total control of the development of the river with $1.4billion of federal and city funding’. Sounds like us in 1983 when the LDDC started to insist they knew what was best for us in Rotherhithe. And it is not just the years of activism that hurts, as he puts it, this has been: “… a 40 year Performance Artwork aimed at raising awareness of the plight of the river’. A Performance Artwork no less, and certainly no more as Lewis is not about to conceptualise this art work for us given what he now has to do with Frank coming into town and all.

Well, of course Lewis is not alone, for way back when in 1992, I remember Andrea Phillips working with the London-based artists and activists Platform on the Lost Rivers of London project and the ‘Effra Redevelopment Agency’, a lovely spin on the LDDC. A congruent, coeval and critically adjacent spin that reminds us of the circularity of our practices, the shared influences of our small wins and devastating losses, our coeval creations and critical disagreements, our ‘our’, always having been at stake and always will in an ongoing association of social justice and commitment to communality.

[1] ‘Lay Theatre’, Theatre & Everyday Life (Routledge: London, 1995).

Download this article as PDF

Alan Read

Alan Read is Director of Performance Foundation and Professor of Theatre at King’s College, London. He was co-ordinator of The Council of Europe Workshop on Theatre and Communities for Dartington College of Arts between 1981-83. He went on to work alongside David Slater, Director of Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop in the Docklands area of South East London through the 1980s. In the 1990s he was Director of Talks at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. He was appointed Professor of Theatre at Roehampton University in 1997 and King’s College London in 2006. Read is the author of Theatre & Everyday Life: An Ethics of Performance (1993), Theatre, Intimacy & Engagement: The Last Human Venue (2008), Theatre in the Expanded Field: Seven Approaches to Performance (2013) and Theatre & Law (2015). He worked with Andrea Phillips as the editor of The Fact of Blackness: Frantz Fanon and Visual Representation (1996). Read’s most recent work has included writing for radio, Plato’s Cave (BBC Radio 4, 2013,) and Dreadful Trade (BBC Radio 4, 2015). His most recent research concerns the fate of the dramatically insignificant for a book entitled The Theatre & its Poor: Performance, Power and Politics, due in 2017, and All the Home’s a Stage: From Oikos to Auditorium, to be published in 2018.

- Introduction: Community Arts? Learning from the Legacy of Artists' Social Iniatives

Andrea Phillips - Pass the Parcel: Art, Agency, Culture and Community

Nina Edge - What is at Stake in Community Practice? What Have We Learned?

Jason E. Bowman - Navigating Community Arts and Social Practice: a Conversation about Tensions and Strategies

Laura Raicovich and Prerana Reddy - Lay Theatre and the Eruption of the Audience

Alan Read - Drawing Lines across History: Reactivation and Annotation

Ed Webb-Ingall - Five Takes on Collaborative Practice and Working with Artists, Non-artists and Institutions: Introduction

Anna Colin - Take One: "Affection, Protection, Direction”

Wendy Harpe - Take Two: "Between Community Arts and Socially Engaged Practice"

Ania Bas - Take Three: "From Community Practice to Gallery Education"

Emily Pringle - Take Four: "Beyond the Mural"

Marijke Steedman - Take Five: "Participate in What is Already Going On"

Ana Laura López de la Torre - Colophon