Learning from Liverpool: An Introduction

Emily King and Prem Krishnamurthy

Learning from Liverpool at K, [K-Komma], Berlin, 16 March 2018. Photos: Dirk Dähmlow, kurtkurz.com

“Every event is a rehearsal for the next event.”

Arrival, the science-fiction blockbuster based on a novella by Ted Chiang, focuses on an encounter with a mysterious alien species that comes to Earth. Working together, a human linguist and physicist attempt to decipher the alien’s unfamiliar, grapheme-based written language, which follows categories and logic wholly different from the humans’ own. What the team discovers is that, for the aliens, time is not sequential but rather simultaneous—the future, past, and present are all collapsible into a single moment, which can assume any order. This recognition catapults the humans into a new understanding of their personal and political histories and trajectories. With this film and its temporal structure as a leitmotif, let’s looks backwards in order to look forwards (and perhaps then back again).

In November 2017, we launched (with co-curator Joasia Krysia) an exploratory, three-day symposium, “Design & Empire [working title]”, in collaboration with the Liverpool Biennial and Liverpool John Moores University. The event came together swiftly and decisively, but with little time for reflection—leaving us afterwards with ample documentation yet lingering questions. As the “[working title]” in our event moniker suggests, we knew that this symposium would be an initial starting point for further investigations, rather than a presentation of decisive conclusions. So we regrouped in March 2018 in Berlin-Schöneberg at K,: a “workshop for exhibition making” curated by P. Krishnamurthy in cooperation with KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The mission of K, (pronounced “K-Komma”) is to offer space and time for discussion, reflection, production, and presentation—as such, it made sense to dedicate one of its first public programs to a brief workshop for debriefing from the Liverpool symposium.

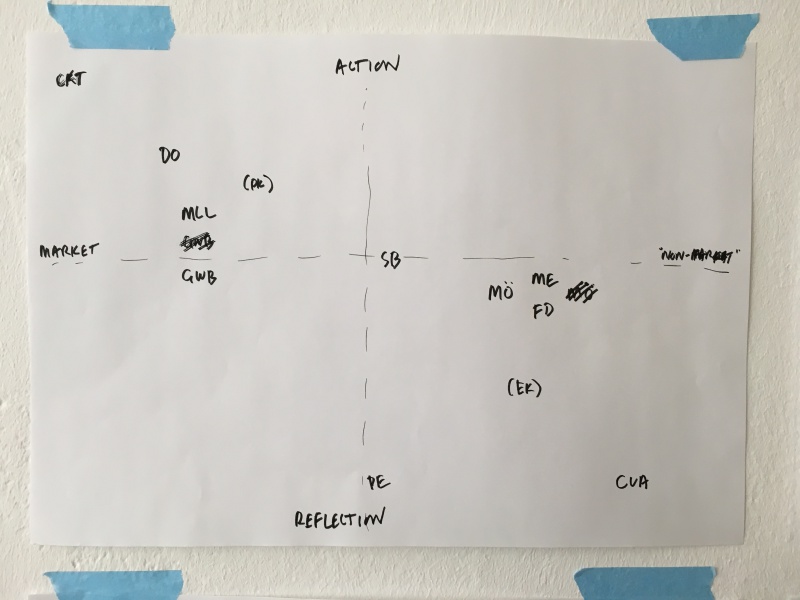

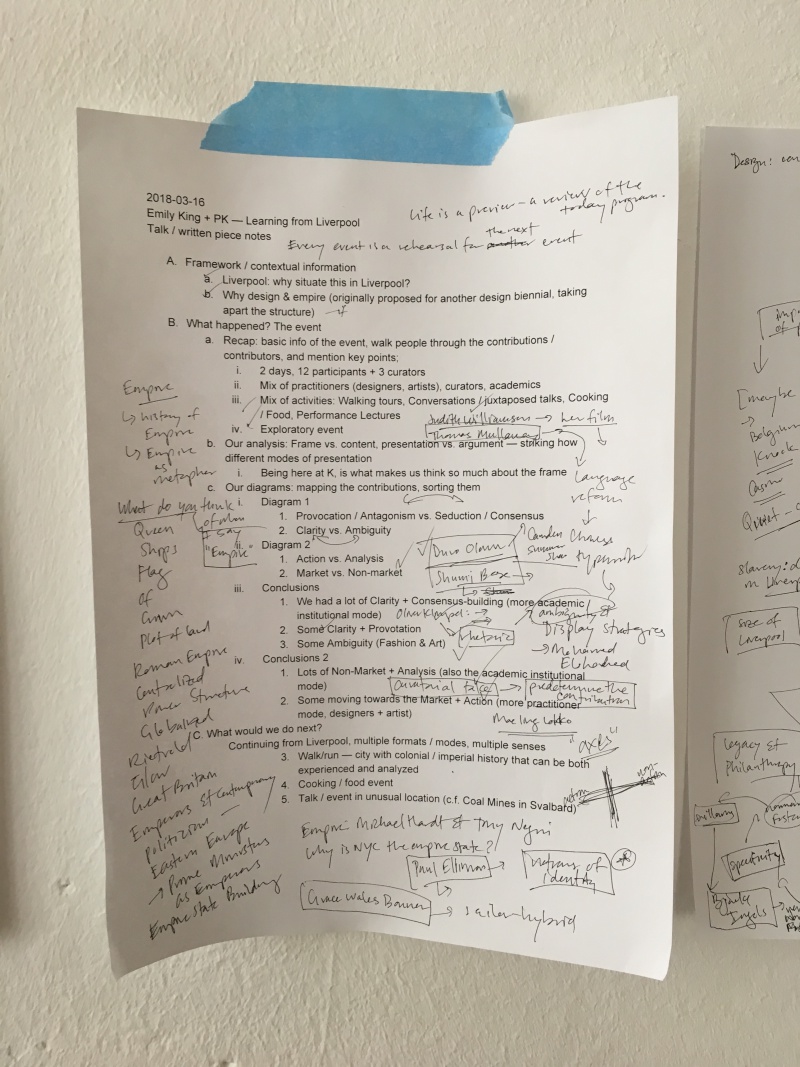

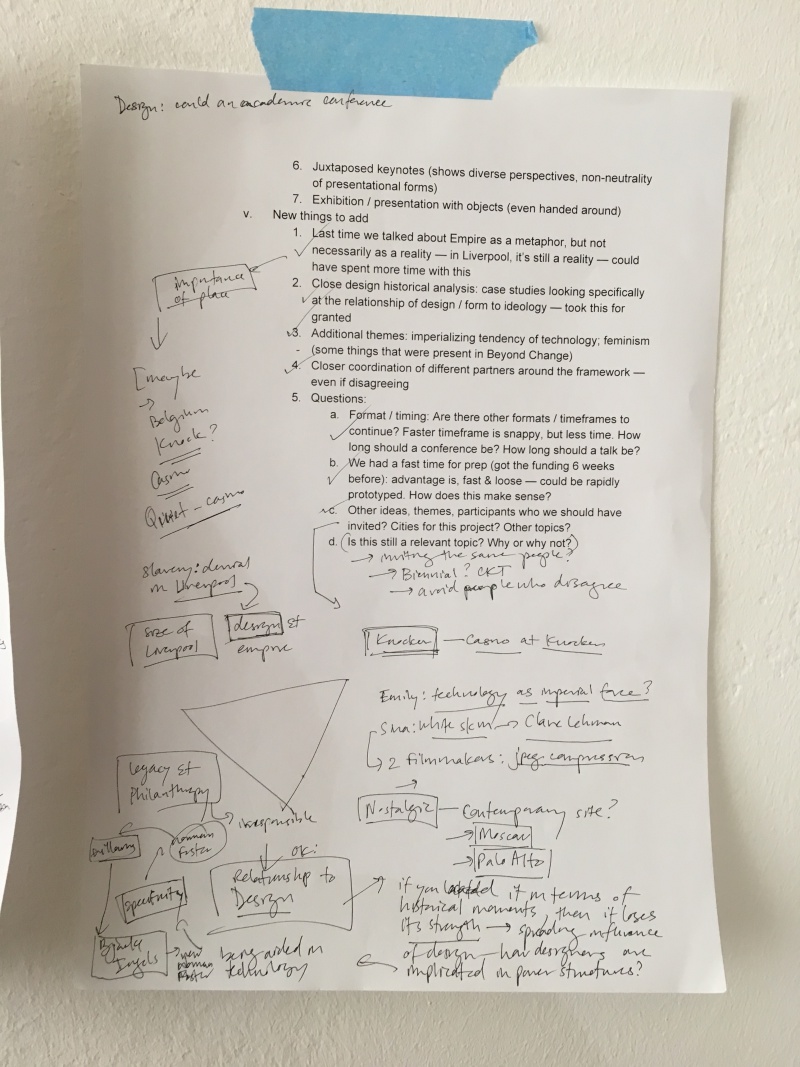

Our workshop format developed organically. The first half day responded to the physical exhibition space of K, itself—with its soft walls and open architecture—where we pinned up objects by each participant from Liverpool. These contributions, ranging from graphic ephemera to printed output to magazine spreads and an immersive video, made visible the conversations that emerged during our symposium; their arrangement annotated and extended the historical works already on view of East German designer and exhibition maker Klaus Wittkugel. The next morning, with these aides de memoire on hand, we focused on analyzing and diagramming the participants and structure of the original “Design & Empire [working title]” event to understand for ourselves the connections between the different contributors and which aspects of the topic each had addressed. The final half day lent us time to outline our thoughts for an evening public program, in which we used the objects in the space as proxies for recounting the symposium’s curatorial process and individual presentations, while soliciting audience feedback on the event’s structure—an in-gallery talk about a past event that then loops forwards to organize this introduction.

The symposium itself, Design & Empire [working title], used these twin terms to consider a broader question: how different forms of historical and contemporary power are shaped and distributed through the material goods and processes that are the products of design. Recent biennials and major exhibitions of design have focused on the field’s increasing influence and its humanitarian effects – shows to bolster the discipline’s self-image and public acceptance. Moving away from these, we hoped to highlight a more sinister aspect of the field: how it contributes to existing and emergent power structures, participating in the systems that help to control our world. At the same time, the symposium, situated within Liverpool, a city with its own submerged colonial history – as well as a key location for the Brexit vote, with 58.1% of the city’s citizens voting to remain – sought to bring this potentially educational perspective to a broader group of students and practitioners who might consider anew the field’s potential. Reflecting its exploratory rather than definitive approach, the symposium took multiple formats – including a keynote lecture, a participants’ dinner, presentations, conversations, lecture-performances, film screenings, guided tours, and even a culinary event. The participants themselves came from varied specializations, and included practitioners, theoreticians, and critics. Interestingly, almost none of the participants had ever met each other before, rare in a cultural gathering of this type. Such diversity also supported our structuring principle that the symposium should be multivocal rather than authoritative or monolithic.

If we could go back to the event again, with our knowledge from today, how might we organize the symposium differently? On a formal level, although our multiple modes of discourse and discovery created a mix of experiences, the inclusion of an actual exhibition – or even a presentation of objects, for observation and perhaps handling – could have helped to ground the weekend’s activities. There were also nodes of content missing from the speaker lineup. For example, “empire” was often discussed as a metaphor, but in a place like Liverpool, it’s still a lived reality – embedded in the city’s infrastructure and built environment. And, as we discovered on our walking tour through waterfront architectural sites, some residents of Liverpool still see the physicallegacy of historical colonialism as a source of pride, despitethe destruction wreaked elsewhere. Our symposium lacked close readings of historical design, case studies that might specifically examine the relationship of design decisions to ideology. Given our own studies and focus, we may have narrowly assumed that this understanding of the political implications of form would be obvious to the symposium’s multiple audiences. Although no symposium can be comprehensive, other themes left unmentioned included the imperializing tendencies of contemporary technology and the power structures of patriarchy.[1]

In our public program in Berlin, we opened this self-reflection up to the audience to ask for their feedback. What were their immediate associations when we mentioned the word “empire”? How could the location of a symposium relate to its contents, and what might be other places for a future conference such as this? Are there locations that look to contemporary questions of empire rather than historic ones? What topics were missing from our initial agenda? In what other ways are today’s designers implicated within emerging power structures? And is the topic of “empire” even still relevant? Why or why not?

In the spirit of the symposium itself, as well as our follow up workshop and event, we’ll leave these questions unanswered – or rather, for you, the reader, to consider as you leaf through the documentation and contributions that came out of the event. We hold out hope that, as in Arrival, there may still be time for the future to inform the past.

Notes and diagrams from Learning from Liverpool workshop. Photograph courtesy K,, Berlin.

[1] The Swiss Design Network’s 2018 research summit, Beyond Change: Questioning the role of design in times of global transformations, addressed topics related to our own in a diversity of formats and approaches. We were lucky to have a chance to attend this before our own workshop in Berlin and reflect upon it in conjunction with our own 2017 symposium.

Download this article as PDF

Emily King and Prem Krishnamurthy

Emily King is a London-based curator, writer, and design historian. She has organised several major exhibitions, including a career retrospective of Alan Fletcher for the London Design Museum, the interdisciplinary exhibition Wouldn’t it be nice: wishful thinking in art and design for the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, special exhibitions for EXD Design Biennale in Lisbon, as well as a touring exhibition of Richard Hollis at Centre Pompidou, Paris, and Artists Space, New York. She has edited monographs on designers including M/M (Paris), Robert Brownjohn, and Peter Saville. In addition to contributing to a range of magazines, such as Apartamento and Fantastic Man, she has edited The Gentlewoman and frieze.

Prem Krishnamurthy is an exhibition maker based in Berlin and New York whose work incorporates curating, design, writing, and teaching. He established and directed the experimental exhibition space P! in New York’s Chinatown and has curated exhibitions at institutions including Stanley Picker Gallery at Kingston University London, Para Site in Hong Kong, Austrian Cultural Forum New York, and The Jewish Museum in New York. He is a partner and director of Wkshps, a multidisciplinary design workshop that develops identities for the arts, culture, and beyond. As co-founder of design studio Project Projects, Prem was the recipient of the Cooper Hewitt’s 2015 National Design Award for Communication Design, the USA’s highest recognition in the field. He is a member of the Creative Team for the Carnegie International, 57th Edition, 2018, as well as co-Artistic Director of the inaugural Fikra Graphic Design Biennial in Sharjah (UAE) and co-curator of the 13th A.I.R. Biennial Exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery, New York.

- Notes on Design & Empire

Joasia Krysa - Learning from Liverpool: An Introduction

Emily King and Prem Krishnamurthy - Empire Remains Christmas Pudding

Cooking Sections - Contents of Ostrich’s Stomach

Paul Elliman - Brown is the New Green

Mae-ling Lokko - Designing Brazil Today

Frederico Duarte - UTOPIA and the Metainterface

Christian Ulrik Andersen - Colophon