Contents of Ostrich’s Stomach

Paul Elliman

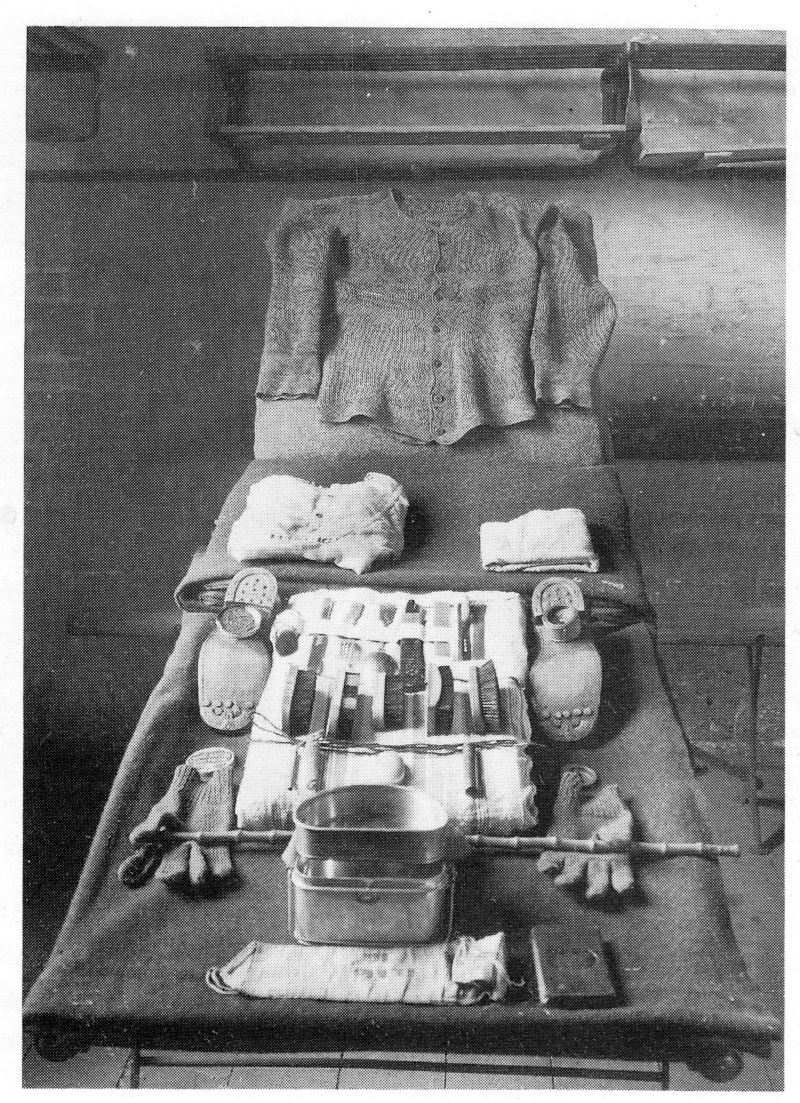

F. W. Bond, Contents of an Ostrich's Stomach, 1930.

No imperialist,

not one of us, in taking what we

pleased – in colonizing as the

saying is – has been a synonym for mercy.

Marianne Moore[1]

Golden Days

I first saw Frederick William Bond’s photograph in the book Golden Days, Historic Photographs of the London Zoo,[2] a selection of images from the Zoological Society of London’s archive of 15,000 glass negatives. The black and white photographs of the collection date back to 1864, with images of many rare animals, some of which have become extinct in the time since they were photographed. A feature of the archive is the growing register of ghost fauna: creatures discarded at the same rate as the ageing media formats that record them. Our own human species can be characterised by the preference to preserve a record of itself over anything more environmentally beneficial to the world around it. Among animals in the archive that have been photographed and lost – and that means never to be recalled – are the thylacine, a sleek wolf-like Tasmanian marsupial with the stripes of a tiger, and the mysterious quagga. Resembling a zebra-headed horse, the last recorded quagga died in Amsterdam Zoo in 1883.

Published in 1976, Golden Days mainly includes photographs from the years between the two world wars. The ‘golden days’ of the title and the sepia-toned images reflect the imperial fantasy of a sun that never sets – despite casting some of its coldest shadows over a visit to the zoo. The ostrich photograph is a particularly bleak one, but few in the book are any less sad or disconcerting. An elephant being walked past Kings Cross station on its way from East London docks, a camel pulling a lawnmower, a polar bear begging for food. The book portrays the sedated life of caged animals trapped in a human wilderness of boredom, or in the case of the absent ostrich, only its death. As the caption tells us, Bond photographed A collection of objects in the stomach of an ostrich at post mortem in 1927 – coins, staples, screws, nuts, rope, and even shirts. Before feeding of animals by the public was stopped, deaths quite often occurred. Laid out on a board like the forensic remains of a pathologist or a taxidermist, or even a hardware-store fire sale, the collection of relics is a memento mori for a specimen of our planet’s largest bird, killed in captivity after being fed on a diet of human debris. The carefully assembled shrine includes metal tokens and folded fabric, a lace handkerchief, a glove, a pencil, and near the centre of the collection, the fatal four-inch nail that killed the ostrich.

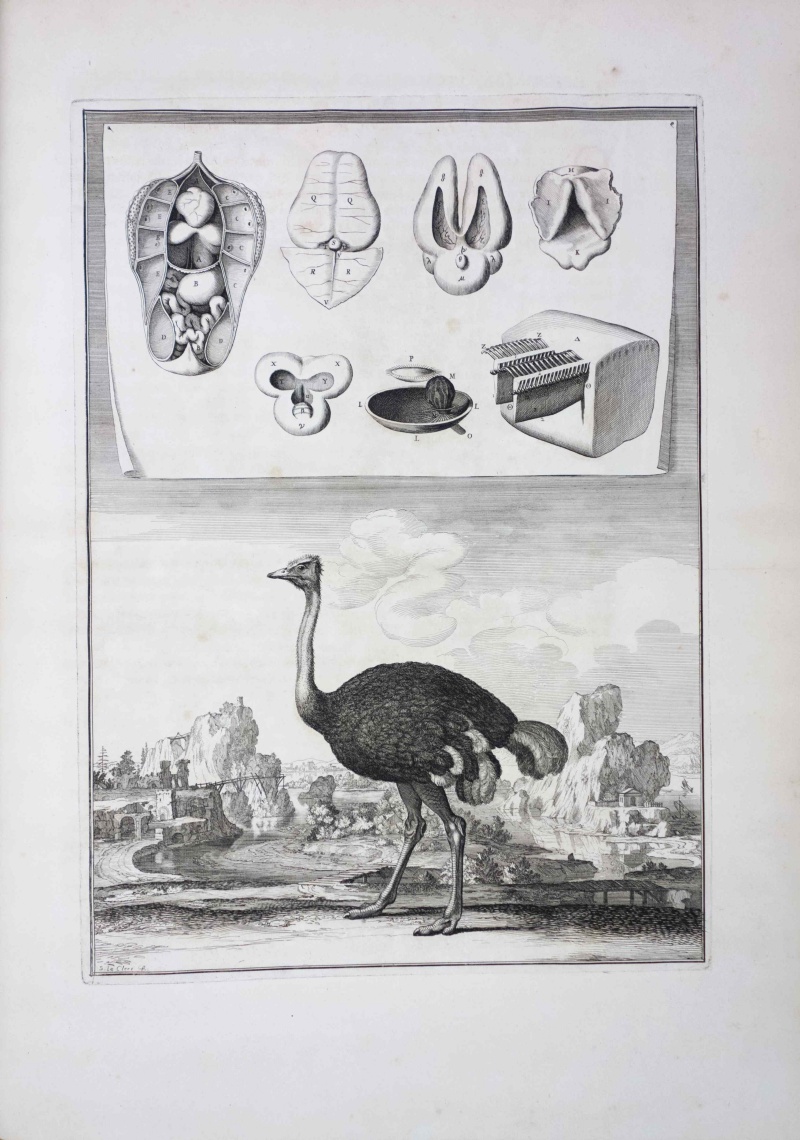

Ostrich dissection from Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire naturelle des animaux (Paris: De l’Imprimerie royale, 1671). Edited by Claude Perrault and first published in 1671, with accounts of the natural history, including the dissection, of 13 different species of exotic animals, An elephant folio published on fine paper, it included full-page engravings of each of the animals, most of them drawn by Sébastien Leclerc, one of a stable of artists and engravers supported by the crown. The animals had come to the Paris Academy from the royal menageries at Vincennes and Versailles, following a programme that had begun in the spring of 1667.

A document published in 1864 provides a meticulous account of the dissection of an ostrich undertaken and authored by Alexander Macalister, Demonstrator of Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. In the introduction Macalister writes:

though the subject of this memoir has been examined very frequently, there does not exist, to my knowledge, a complete account of its structural peculiarities. M. Perrault has left on record the dissection of eight of these birds; but many interesting facts regarding the visceral anatomy are not mentioned. During the past year the splendid pair of ostriches belonging to the Zoological Society of Dublin died – the female in June, 1863; the male in January, 1864: both have been dissected with great care, and many novel points of anatomical and physiological importance have been ascertained.[3]

The notes fill a 24-page document covering every detail of each creature’s body. A passage describing the contents of their stomachs includes the following:

All the substances contained in the stomach were of a dark green colour; as also was its epithelial coat; its contents were vegetable matters and stones in large quantities – the latter were rounded and worn. In the outer coat of the stomach of the female, and in contact with the gastric artery, a pin was found, enclosed in a cyst.[4]

‘OSTRICH Can digest stones’[5]

Bond’s photograph is a picture of desolation. But not all ostriches are on the extinct list yet. A mythical and dreamlike creature to ancient cultures, the ostrich is uniquely geared for survival, a spectacular composite of physical and behavioural adaptations. Ostriches have the largest eye of any land vertebrate: 50 mm in diameter, or two-thirds of the volume of its head, giving it exceptional vision and shaded from the sun by a thatch of exceptionally long black eyelashes. Birds usually have four toes, the ostrich has only two, but they are seven inches long and with a giant black hoof-like nail on each inner toe. Macalister’s dissection notes contain an extended description of the bones and sole of the foot, ‘where the surface of the skin presents a series of closely-set bristle-like processes’.[6] The body of the bird is visible only as a mass of feathers – ounce for ounce more valuable than gold in the late nineteenth century – with a wingspan of two metres. Ostrich anatomy, however, lacks the ‘keel’ that attaches to the sternum or breastbone of flying birds. Making up for this structural oversight are two kneecaps on each leg, also exceptional for bird or beast. The upper kneecap or patella allows the ostrich to straighten its leg more quickly and forcefully. With its razor-sharp obsidian-black toenail and double-jointed leg, the ostrich is perfectly placed to disembowel a human with a single sudden forward thrust. More importantly, the hoof-like feet and double patellae are the key to its incredible pace, covering five metres in a single stride and sustaining over long distances speeds of up to 70 km/h (43 m/h). Predators have little chance of catching a flightless bird that has invented its own form of flight.

A scene in the eleventh-century Bayeaux Tapestry shows an ostrich beneath a star rising in the June night sky. The ostrich was thought to lays its eggs only after checking for the arrival of the Pleiades constellation. Such speculation is not easily disproved: in the natural habitat of the ostrich, timing is critical, since the chicks must hatch just as the rains arrive.

The ostrich is the only living member of the ratite order of Struthioniformes. Others, including Madagascar’s aepyornis or elephant bird, and New Zealand’s moa (once placed in the ratite group), are gone. Known to have inhabited areas around the Mediterranean Sea in the west, China in the east and Mongolia in the north 20–60 million years ago, ostriches migrated south across Africa as recently as a million years ago. Still native to the African savannahs and the Sahel, the bird has a preference for open semi-desert landscape. This has allowed farmed ostriches in Australia and southern Africa to thrive in large feral populations, while free ostrich numbers are in serious decline. Of five subspecies, the Arabian ostrich became extinct around 1966, and the North African ostrich is on the critically endangered list.

The ostrich has long been an object of our misperception. Believed to feed on stones and metal objects, and to bury its head in the ground, the ostrich is synonymous with a refusal to face reality or accept facts. In a famous line of Henry VI (1591), Shakespeare exploits the tragicomedy of the creature’s ungainly appearance and eating habits when the rebel leader Jack Cade threatens his foe Alexander Iden: ‘I’ll make thee eat iron like the ostridge, and swallow my sword like a great pin.’[7] Visitors to London Zoo may have laughed like Elizabethan theatregoers at the impractical-looking creature’s willingness to eat everything thrown at it, including that great pin. It was part of a popular folklore, whose origins are attributed to the Greek scholar Pliny. He wrote, in Naturalis historia, that the ostrich has a habit of hiding in bushes and an ability to eat and digest anything.[8] For this reason the ostrich takes its place in Flaubert’s satirical Dictionary of Received Ideas. It cannot digest stones or metal objects, and neither does itbury its head in the sand to avoid danger. It does, however, lay its eggs in the ground, using its beak to rotate them during incubation. The black-feathered male takes his parental shift under cover of the night. In daylight, the scrub brown-feathered female can seem to drop invisibly into the ground as a defensive measure, perfectly resembling in the heat haze just another mound of earth. Ostriches also poke around in the sand looking for small hard objects. The ostrich has no teeth and one of its adaptive instincts is to outsource the mechanism for its digestive system to a collection of stones, bones and lumps of metal and glass. Never excreted, they wear slowly away and are replaced. Without this collection of hard objects, the ostrich would die. Ostriches are resourceful, not foolish – a truth conveyed in Shakespeare’s play, with its focus on alimentary issues of resilience, survival and diet. In 1450, during a time of economic and moral collapse after a costly unresolved war with France, Jack Cade led a powerful Kent rebellion against the English Government prompted by a severe national food shortage. Shakespeare connects the impoverished malfunctioning body to social disorder when, at Cade’s death, his final words are ‘Famine and no other hath slain me.’[9]

The American poet Marianne Moore celebrates the ostrich in her poem ‘He “Digesteth Harde Yron”’ (1941). Her title is borrowed from English writer John Lyly’s Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1579), where he writes: ‘the estrich digesteth harde yron to preserve his health’, referring to the discovery by French anatomist Joseph-Guichard Du Verney of a collection of seventy coins in the craw of an ostrich he was dissecting. Moore’s poem was partly inspired by a magazine article on the ostrich, which states: ‘Its fondness for the metals … has obtained for it the epithet of the “iron-eating ostrich”.’[10]

Critic Harold Bloom salutes Moore as a ‘visionary of natural creatures’.[11] So many of them inhabit her poems: frogs, elephants, race horses, snails, the ‘frigate pelican’, the pangolin, the chameleon, the jellyfish and the giraffe. Moore once translated a collection of Fontaine’s Fables, though her own poems were already an updating of the form, fable-like in their own way but featuring creatures that are not in or under the possession of human language. Bloom also wrote that Moore’s best poems are from somewhere ‘at the opposite edge of consciousness’.[12] ‘He “Digesteth Harde Yron”’ is one of these, with its fragmented image of an ostrich as a flickering continuum alive across the passage of time. Freely quoting from Lyly as well as the magazine feature that may have suggested the poem, Moore balances lucid thought against a world of never fully knowable things, or certainly no better known because they can be named. Impressions of reality are instead gleaned from their attributes, and in ‘He “Digesteth Harde Yron”’ Moore largely resists directly naming the subject of her poem. It is ‘the camel-sparrow’, ‘the large sparrow Xenophon saw walking by a stream’ and ‘the bird, quadruped-like bird, and alert gargantuan / little-winged, magnificently speedy running-bird’. There is a difference, says Wallace Stevens in a short essay on Moore, between the creature that she wants to think freely about and the ostrich contained by her encyclopedia.[13] ‘Never known to hide his / head in sand’, Moore writes, in defiance of the language of atrophied facts.

The poem is an admiring account of a creature surviving the stages of evolution and the pages of history, having been a prized object of imperial realms from Egypt, Greece and Rome to more recent empires of Europe and America. Maat, Egyptian goddess of law, is characterised by her 'feather of truth’ – an ostrich feather; in Egyptian writing the hieroglyph for justice, it marks the bird as a symbol of integrity. In a recent study of Raphael’s painting of an ostrich, made as part of a fresco for the Vatican (1519–24), historian Una Roman De’Elia, imagines Raphael’s attraction to a curiously formed creature that ‘evoked so many disparate associations – a modern hieroglyph’[14] with its contradictory range of meanings, alternately signifying, among other things, heresy and stupidity or strength and perseverance. In Western culture of the Middle Ages, Raphael’s ostrich would have been particularly ambiguous, partly because its image was so uncommon. Sharing certain affinities with Moore and her ostrich, De’Elia likens the unconventional bird, as depicted by the Renaissance painter, to a ‘rare word, not easily interpreted’.[15]

Other echoes of the past resonate in Moore’s poem, including the biblical Book of Job, with the ostrich prominent among its procession of beasts, lions, ravens, unicorns, horses, eagles and peacocks, and celebrated there for its speed: ‘When she lifts herself on high, she scorns the horse and its rider’.[16] '[T]he best of the unflying / pegasi … he feigns flight’, says Moore, though Baraq Baba, a twelfth-century Sufi dervish, is said to have encouraged an ostrich he was riding to leave the ground and fly a short distance.

After marking its instinct for survival, Moore wonders how such a creature fell from ancient reverence to being branded as somehow both foolish and an icon of imperial decadence:

Six hundred ostrich-brains served

at one banquet, the ostrich-plume-tipped tent

and desert spear, jewel-

gorgeous ugly egg-shell

goblets, eight pairs of ostriches

in harness.

The banquet was hosted by the Syrian-born Elagabalus, Roman emperor between 218 and 222, and gaining in those few years a reputation for extreme decadence. A painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), depicts another of the same emperor’s excessive banquets, when guests were smothered beneath a mass of violets and rose petals released from a false ceiling, some apparently suffocating in the blizzard of flowers. Elagabalus ruled for four years and was only eighteen when assassinated, his body thrown into the Tiber. In notes for the poem, Moore cites George Jennison’s book Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome.[17] Clearly the ostrich is, for Moore, the opposite of flamboyant gluttony, and through the qualities that have kept it alive, offers a lesson for human behaviour, prompting thoughts, warnings even, about the excesses and prejudices of our own cultural appetites.

The Royal Hunt

Albrecht Dürer, Deer Head Pierced by an Arrow, 1504, brush drawing and watercolour on paper.

The first subject matter for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood. Prior to that, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the first metaphor was animal. Rousseau, in his ‘Essay on the Origins of Languages’, maintained that language itself began with metaphor: ‘As emotions were the first motives which induced man to speak, his first utterances were tropes (metaphors). Figurative language was the first to be born, proper meanings were the last to be found.’[18]

The ostrich appears in another Marianne Moore poem, ‘The Jerboa’, amid scenes in an imperial Roman animal park, possibly an early menagerie, a garden with a temple for the Egyptian goddess Isis, and a giant bronze fir cone that functioned as a water fountain. The Romans, as well as those ‘native of Thebes’, writes Moore, knew:

how to use slaves, and kept crocodiles and put

baboons on the necks of giraffes to pick

fruit, and used serpent magic.

They had their men tie

hippopotami

and bring out dappled dog-

cats to course antelopes, dikdik, and ibex:

or used small eagles. They looked on as theirs,

impalas and onigers,

the wild ostrich herd

with hard feet and bird

necks rearing back in the

dust like a serpent preparing to strike.[19]

The earliest record of such parks, a form of private ‘paradise’, comes from China around 1150 BC under the Emperor Wen Wang, and evidence can also be found in the empires of Assyria and Babylonia and later in the Egyptian dynasties. The Persians created paradeisos – large walled parks stocked with living creatures for the pleasure of the monarch. The keeping of menageries in which animals were caged together according to classification or family groups – all the felines, for example – appeared later, more as a collection of living trophies kept on the grounds of the palace. The fifteenth-century Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) is thought to have had the grandest menagerie of this time, a zoological and botanical collection capturing the spirit of the Aztec empire.

From Mesopotamian, Persian and Hellenistic empires to our own times, animals have provided a symbolic capitalfor imperial power, displayed to impress an emperor’s subjects as much as his enemies, and used as objects of exchange in a common language connecting Latin, Christian and Islamic worlds. The opening scene of the twelfth-century French poem La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland) involves the offer of a royal gift of a collection of animals. The scene is based on actual exchanges from the time. Historian Willene Clark pictures England’s King Henry I, after victory at Caen in 1105, parading ‘a young lion, a lynx, camels, and an ostrich before a populace that followed the animals with exuberant pleasure and wonder. The message is of a ruler so powerful he could acquire and control even these fearsome, wild, and expensive creatures.’[20] The royal interest in exotic animals at this time was motivated by a twelfth-century revival of Classicism, an age when animals imported for ceremonial processions and menageries were imperial Rome’s most effective symbols of power.

Similarly the institution that Thomas Allsen calls the ‘royal hunt’ was central to every aspect of life in premodern Eurasia:

To understand the royal hunt we must take into account the myriad ways in which animals, wild and domesticated, are entwined in human cultural history: animals, after all, are foes and friends, symbols and signs; they serve as talismans, as markers of status, as commodities and presentations, as sources of entertainment; clothing, food, and medicine, and even as sources of wisdom and models of human behaviour.[21]

Over a period of nearly four millennia, different courts and cultures across Iran, North India, Turkestan and much of Eurasia, while rarely in direct contact with each other, came to share many of the same hunting practices and rituals. Stately parks and the exchange of animals were important to military preparations, trading routes and communication networks, as well as claims for political legitimacy. Birds and beasts featured as stylised courtly motifs, which, along with the possession and exchange of actual animals, became unifying elements in the medieval language and culture of empire. Elephants from India and Southeast Asia were often ‘recycled’ in royal exchanges across Latin Europe, as we know from Pietro Longhi’s quartet of paintings of an elephant in Venice in 1774.

Allsen’s study follows the imperial significance of hunting and of protected parks and menageries well into the twentieth century. In 1940, Time magazine ran a cover story about ‘Reich Master of the Hunt’ Herman Goering. Hitler’s deputy lived in Schorfheide Forest, developed by him as a private 100,000-acre game preserve. Importing falcons from Iceland and commissioning a genetically engineered resurrection of the extinct auroch, a prehistoric cow depicted in cave paintings and once hunted by the Romans, Goering dressed in medieval hunting costume to practice archery and expected his guests to play with Caesar his pet lion cub. In every detail, including the sacrificial destruction of his own hunting park at the end of the war, the Reichsmarshall was observing traditional practices commonly shared by earlier imperial Eurasian powers. Identifying with imperial Rome, The British Empire also exploited the symbolic value of animals and the historical significance of the royal hunt – maintained at home in the traditional blood-letting of the fox hunt.

London Zoo was the first royal menagerie to be described as a zoological garden. A national repository dedicated to public animal display, it offered the first reptile house and the first insect house. When, one evening in 1867, a popular music hall artist known as the Great Vance sang, ‘Weekdays may do for cads, but not for me or you / The OK thing on Sundays is the walking in the zoo’, the popular abbreviation was coined.[22]

Along with the British Museum and the Royal Geographical Society, London Zoo was part of a network of domestic institutions serving to extend the symbolic value of the British Empire. Echoing the assembly of animals in Noah’s ark, the Zoo registered the acquisition of distant territory through its display of exotic creatures. In Reading Zoos, Randy Malamund considers the zoo as a domestic analogue to the colonialist literature of Rudyard Kipling, Howard Forster and others.[23] Connecting it to what Robert H MacDonald has called the ‘metaphorical construction of empire’,[24] Malamund describes the carefully staged ‘native’ scenario in which animals are figures in a text authored by those who capture, breed, administer and exhibit them. In this model of empire, visitors hold dominion over lesser species in a sociopolitical hierarchy of morally indefensible values.

Confirming London Zoo’s manifestly imperialist roots, Sir Stamford Raffles, with a reputation made as an administrator of England’s imperial outposts in Asia, ended his career by establishing the Zoological Society of London in 1826. His personal collection of animals, mainly from Sumatra where he was governor, formed part of the zoo’s opening endowment. As both trader and administrator, Raffles embodied the link between imperialism and the collection, imprisonment and display of animals. He also extended the royal hunt to global proportions by establishing, as part of the Empire, the modern commercial legacy of the menagerie in the form of the zoo.

Regal associations with ostrich feathers may have begun a few centuries earlier with Queen Elizabeth I, but in the late nineteenth century British colonial interests in South Africa led to a hugely lucrative Cape ostrich feather industry. Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee of 1897 in a gown of black satin ruffled by a thousand ostrich feathers. A photograph from 1902 that seems to appear in every book about the British Empire shows the Viceroy Lord Curzon, his wife Lady Curzon, and the corpse of a Royal Bengal tiger, another creature granted imperial status through no choice of its own. The basis of imperialism is portrayed here in the visualised power structure of a tradition that attempts to keep its ideals separate from how they are achieved, or from what Joseph Conrad described as a horror ultimately impossible to conceal:

The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea – something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to.[25]

The Viceroy and his tiger reminds me of two less triumphal animal-kill depictions, each written by a well-known subject of the British realm: ‘Shooting an Elephant’ byGeorge Orwell, and ‘Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine’ by DH Lawrence, both dated to within a couple of years of Bond’s ostrich photograph of 1927. Orwell’s story, published in 1936, tells of an incident involving a young British police officer working in Burma between 1922 and 1927 (as Orwell was at this time). Lawrence wrote his account on the ranch where it happened in New Mexico in 1925. For both, the shooting of an indigenous animal triggers a rush of thoughts about nature, culture and human progress, symbolised by guns and cages, whether for herding and containing animals or people. In keeping with Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the plight of both elephant and porcupine reflects the irrational barbarity of the supposedly civilising imperial mission.

For Orwell, everything the imperialist cause hopes to conceal rears up in the young policeman’s struggle to deal with the elephant, and in the end, simply to get it to die. The narrator’s indignation at British imperialism emerges from personal discomfort at his own role in defending it:

In a job like that you see the dirty work of Empire at close quarters. The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the lock ups … I had to think out the problems in the utter silence that is imposed on every Englishman in the East. I did not even know that the British Empire is dying.

The incident seems small in the scheme of things, but offers an unavoidable view of what Orwell calls ‘the real nature of imperialism – the real motives for which despotic governments act’.[26] The tyranny of empire destroys even the coloniser’s freedom as the young policeman finds himself on display, performing for the crowd as a puppet while carrying out the wishes of his subordinates in a public theatre of hatred.

For Lawrence, the porcupine represents the incommensurable scope of the frontier. Face to face with the animal, he contemplates the cosmic vastness of land and sky: ‘The ranch is lonely, there is no sound in the night, save the innumerable noises of the night ... Cosmic noises in the far deeps of the sky, and of the earth.’ Seen in the light of the moon, the porcupine has a ‘lumbering, beetle’s squalid motion, unpleasant’. He watches it ‘squat like a great tick’, the hairs and bristles forming a moonlit aureole that seems ‘curiously fearsome, as if the animal were emitting itself demon-like on the air … He made a certain squalor in the moonlight of the Rocky Mountains. As all savagery has a touch of squalor’. Yet ‘the dislike of killing him was greater than the dislike of him … never in my life had I shot at any living thing. I never wanted to. I always felt guns were repugnant: sinister, mean.’ However, he heads back to the house for the ‘little twenty-two rifle’.[27]

All British military police in Burma carried a gun, but as Orwell knew, it was ‘an old .44 Winchester and much too small to kill an elephant’. Sending an orderly to borrow an elephant rifle raises the already excited expectations of the crowd that has gathered to watch the spectacle:

As soon as I saw the elephant I knew with perfect certainty that I ought not to shoot him. It is a serious matter to shoot a working elephant, comparable to destroying a huge and costly piece of machinery … I watched him beating his bunch of grass against his knees, and with that pre-occupied grandmotherly air that elephants have.

Finally, both men fire rounds of shots into their doomed creatures, killing them as incompetently as you and I might, if we could carry it out, in a frenzy of mindless noise and smoke and bullets, a small-scale devastating carnage. ‘One could have imagined him thousands of years old’, says Orwell of the dying elephant, no longer an imperial machine but returned to the land, ‘a once living rock formation now expiring its last breath’.

Neither narrator offers any sense of concern for these animals. Lawrence drifts into cosmic reverie about a natural-universal order of all creatures and kills the porcupine because, well, that’s what you do to them. Orwell’s reason is even worse: ‘I had done it solely to avoid looking a fool’.[28] There is no sentiment here that compares with the dignity bestowed by Marianne Moore on the porcupine in her ‘Apparition of Splendor’: ‘as when the lightning shines on thistlefine spears among/prongs in lanes above lanes of a shorter prong’,[29] or the elephants in her eponymous poem:

wistaria-like, the opposing opposed

mouse-gray twined proboscises' trunk formed by two

trunks, fights itself to a spiraled inter-nosed

deadlock of dyke-enforced massiveness.[30]

Language and Empire

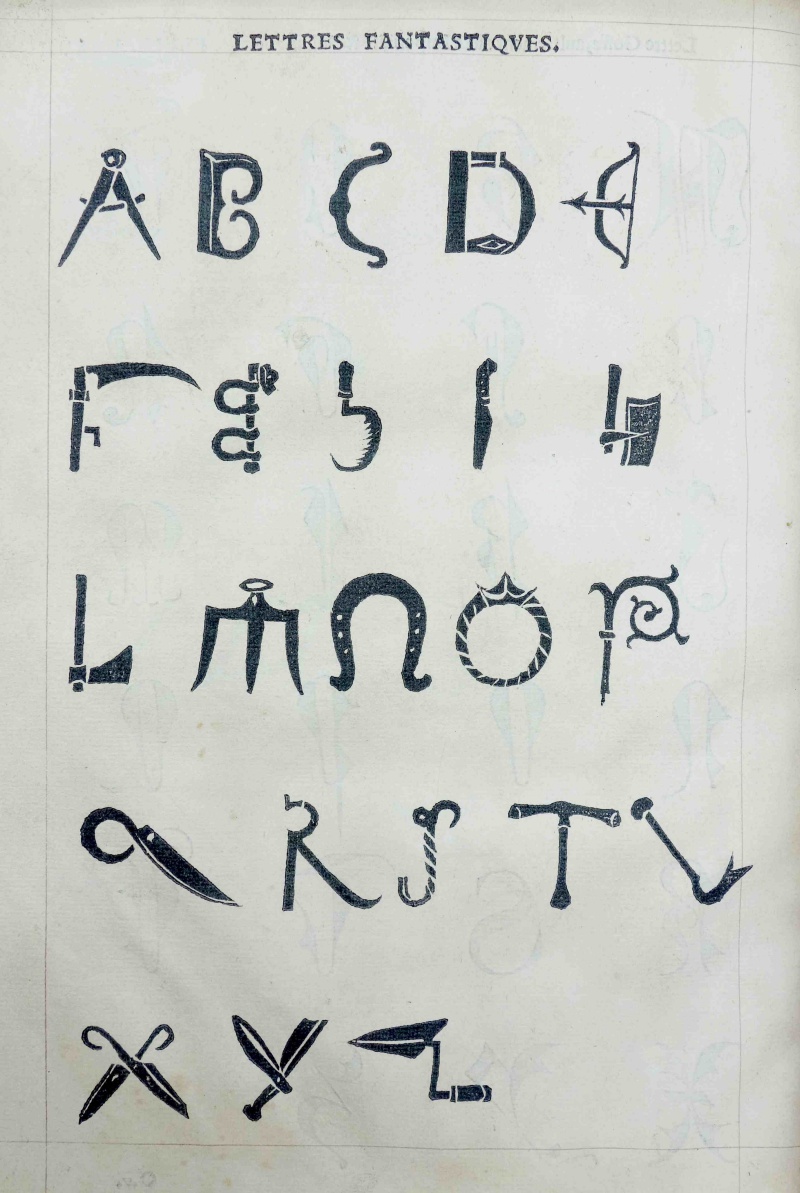

Abraham de Balmes, Letters Fantastique (1523), from Geoffroy Tory, Le Champs Fleury, 1529.

Abraham de Balmes’s Letters Fantastique is believed to have been made in Venice in 1523. De Balmes referred to it as ‘writing from beyond the river’,[31] perhaps to give the impression of Mesopotamian origins, or, since it was made in Venice, discarded parts dredged from a canal. Some of the objects comprising the letters are weapons for battle – a tomahawk, an archer’s bow with arrow primed – but most seem to be agricultural and gardening tools: a scythe, a hoe, a trowel, cutting blades. All of these implements are of wrought iron, and at the centre of the collection is the blacksmith’s trademark, usually paired with the image of an ostrich, a horseshoe. This pairing was also present in the crest of English soldier Captain John Smith, who established a permanent colony in Virginia in 1609. Thus imperialism and the ostrich meet again in a third Marianne Moore poem, ‘Virginia Britannia’ (1935). Here, the poet imagines the natural features, the flowers, trees, animals and particularly the birds, of Virginia, in the days before it became North America’s first permanent European settlement. Moore’s notes for the poem refer to ‘the ostrich and horseshoe: As crest in Captain John Smith’s coat of arms, the ostrich with a horse-shoe in its beak – i.e. invincible digestion – reiterates the motto, Vincere set vivere’.[32]

In Orientalism, Edward Said evaluates the rise of philology and the nineteenth-century interest in histories and cultural implications of language.[33] Many of the first-wave Orientalists were scholars of language, including Ernest Renan, a noted Phoenician archaeologist, Silvestre de Sacy, a historian of Semitic and Arabic languages, both from France. Among the English were Edward William Lane, a translator and Arabic lexicographer, and the explorer Richard Burton, a linguist who worked as a cartographer and spy for the East India Company. Said presents the following stomach-churning passage from Lane’s bookModern Egyptians as the epigraph for his chapter:

When the seyyid ‘Omar, the Nakeeb el-Ashraf married a daughter … there walked before the procession a young man who had made an incision in his abdomen, and drawn out a large portion of his intestines, which he carried before him on a silver tray. After the procession he restored them to their proper place and remained in bed many days before he recovered from the effects of this foolish and disgusting act.[34]

Lane admits in his book to not being present at the procession described. The scene was reported to him, along with others ‘so much more singular and disgusting’ that he refuses to tell of them.[35] They might have involved sex, all references to which Lane censored from his translation, the first in English, of The Arabian Nights. Burton made up for that with the first unexpurgated translation of One Thousand and One Nights (commonly called The Arabian Nights in English after Lane’s translation, based partly on Antoine Galland’s French edition) and by publishing the Kama Sutra in English, and a translation of al-Nafzawi’s Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight, a fifteenth-century Arabic sex manual and collection of erotic literature. At odds with the ethnocentrism of his peers and critical of British colonial policies, Burton relied on direct contact with other cultures. He also seemed to acquire languages easily, apparently able to communicate in twenty-nine European, Asian and African languages, with a proficiency in several Indian dialects as well as Persian and Arabic. Additionally, he kept a menagerie of tame monkeys with the intention of learning their language.

India and the Orient occupy a complicated place in European western experience. Bordering Europe it was the location of its earliest and most profitable colonies. As the site of the Biblical lands, it is the source of its civilization and languages. At the same time, for colonialism, the Orient marks a mutually exclusive distinction between two separate worlds. Said shows how the early Orientalists provided a setting for subsequent studies almost entirely congruent with the interests of imperial institutions and governments. In the years between the late eighteenth century and the end of World War I, Europe had colonized 85 percent of the world, with a dramatic effect on domestic aspects of national interest. Benedict Anderson covers the same years in his book Imagined Communities, a time when nationalist enterprises of discovery and conquest ‘caused a revolution in European ideas about language’.[36] The rise of nationalism across Europe between 1820 and 1920 is closely connected to the growth of literacy and national print languages. The ‘nation’ becomes something more clearly articulated and aspired to, but is also conceptually available for other interpretations. The convergence of capitalism and literacy on what Anderson refers to as ‘the fatal diversity of human language’[37] brought newly idealised forms of national collectivity. Such concepts, shaped on the printed page in vernacular national languages, were the impetus for all kinds of imaginary citizenship, shared popular sovereignty, national flags and anthems. Print-literacy helped to establish the invented traditions that could define a new national authority. At the same time, the emergence of a humanist philology incorporated classical history and the Bible as part of a notional ‘antiquity’ to be juxtaposed with an emerging conception of modernity. Nations began to think of their own culture as equal to the ancients, and to impose this onto others.

By the late eighteenth century, comparative language studies brought knowledge of Sanskrit and the awareness that Indic culture was far older than Greece or Judaea. Jean-François Champollion’s deciphering of the Rosetta Stone in 1822 encouraged a surge of interest in ancient languages and early writing systems. Studies of comparative grammar followed, often involving the speculative reconstructions of proto-languages. The nineteenth century was a golden age for lexicographers, grammarians and folklorists, in a Europe in which Latin had been defeated by vernacular print-capitalism. So-called languages of state were now manifest in the vernacular languages of its citizens and connected to a rapaciously expanding print market.

Canadian political economist Harold Innis, known for writing about language and empire, first produced a series of studies looking at Canada’s fur, fish, timber, metal and mineral industries. Acknowledging his country’s defining role as a resource for staple products, the timber was a turning point in his work. Empire propaganda was being published on pages of decimated Canadian forest. The demands for pulp and paper were directly connected to the mass-circulation of daily newspapers, and mass media made a great impact on public opinion in cities such as London and New York. In his book Empire and Communications (1950), Innis explores this as a feature common to all empires.[38] Conditions are made favourable to imperial interests by the efficiency of their means of communication. When the Romans conquered Egypt, supplies of papyrus became the basis of a large administration empire. The nineteenth-century growth of literacy and print technology is historically consistent with that. So is the influential force of the writer Rudyard Kipling, a propagandist for British imperialism in the form of popular fiction, songs, poetry and children’s stories.

Among surviving fragments from Greco-Roman Egypt, literature – including Homer and Aristophanes – is far outweighed by contracts, tax receipts and property-sale documents. By the nineteenth century, these kinds of writing are still the bulk of what remains, but journalism and fiction have become an additional instrument of imperialism, another way to colonise ideas and social space. For Said, ‘the power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging’ is an essential means of connecting the empire to its subjects at home.[39] Kipling supplied this narrative connection in book-loads and across all registers of language, from the tone of an Old Testament prophet to that of a bar- and barrack-room balladeer. He sold the adventure of Empire as a thrilling yarn, setting British expeditionary forces on a magical mission as part of a hereditary ‘tribe’ that he named ‘The Lost Legion’ – inheritors of the spirit of the Roman Empire and not only its alphabet. But his darkest and most compelling stories are a form of colonial gothic that seems to emerge from his own perversely irrepressible attraction to everything the imperialist fears most in the shadowy hostile corners of colonial life.

In his short story ‘Beyond the Pale’, a Hindu woman sends a message to her lover in the form of an object letter, a collection of things. The story, published as part of Kipling’s first book of short fiction, Plain Tales From the Hills (1897), describes the forbidden relationship between a British civil servant, Trejago, and a native girl, Bisesa. In the words of the narrator, it is the cautionary tale of a man who ‘stepped beyond the safe limits of decent everyday society, and paid for it heavily’.[40] The romantic premise is a pretext. Kipling is a master of the deceptive affairs of language. Generally avoiding first-person accounts, he tends to invent fictional characters as narrators of his stories, while the protagonists, often members of the Anglo-Indian community, are self-projections based on personal experience. In ‘Beyond the Pale’, the nightly excursions of Trejago are drawn from Kipling’s own life as a reporter living in the North Indian city of Lahore and later in Allahabad. The stories included in Plain Tales From the Hills were written for the Lahore-based newspaper The Civil and Military Gazette. In his autobiography Something of Myself, Kipling remembers wandering ‘till dawn in all manner of odd places – liquor shops, gambling and opium dens … the narrow gullies under the Mosque of Wasir Khan for the sheer sake of looking’.[41] It is not known if he chose to go concealed, as Trejago does, in a boorka, the ‘sheet veil’ used by Muslim women, to enable his unchecked passage into Hindu territory. But the narrator’s message in the opening line of the story, ‘A man should, whatever happens, keep to his own caste, race and breed. Let the White go to the White and the Black to the Black’ belongs to Kipling, expressing the purpose of the tale as a premonitory warning to all.[42]

The day after Trejago encounters Bisesa, a fifteen-year-old widow, he receives a ‘packet’ – ‘an innocent unintelligible lover’s epistle’ sent as a collection of objects. ‘No Englishman should be able to translate object-letters’, says the narrator, but Trejago, who knows ‘too much about these things’, is different. Spreading out the contents of the package, he begins to ‘puzzle them out’:

A broken glass-bangle stands for a Hindu widow all India over; because, when her husband dies, a woman’s bracelets are broken on her wrists. Trejago saw the meaning of the little bit of glass. The flower of the dhak means diversely ‘desire’, ‘come’, ‘write’ or ‘danger’, according to the other things with it. One cardamom means ‘jealousy’, but when any article is duplicated in an object-letter, it loses its symbolic meaning, standing merely for one of a number indicating time, or, if incense, curds, or saffron be sent also, place. The message ran then – ‘A widow – dhakflower and bhusa– at eleven o’clock’. The pinch of bhusa enlightened Trejago. He saw – this kind of letter leaves much to instinctive knowledge – that the bhusa referred to the big heap of cattle-food over which he had fallen in Amir Nath’s Gully, and that the message must come from the person behind the grating; she being a widow. So the message ran then – ‘A widow in the Gully in which is the heap of bhusa desires you to come at eleven o’clock.[43]

Trejago begins a secretive relationship with Bisesa, and when her uncle finds out he punishes his niece. After a three-week break from visiting, Trejago is greeted by the shocking sight of the young girl’s arms held out in the moonlight: ‘both hands had been cut off at the wrists, and the stumps were nearly healed’. Then, ‘some one in the room grunted like a wild beast and something sharp – knife, sword, or spear – thrust at Trejago in his boorka. The stroke missed his body, but cut into one of the muscles of the groin, and he limped slightly from the wound for the rest of his days.’[44]

Sara Suleri, in her book The Rhetoric of English India (1992), identifies an important key to the mass appeal of Kipling: his ideological representations of the British Raj carried the urgency and novelty of news reports and magazine articles.[45] Typically, he would add details to convey an additional sense of realism, such as the epitaph of ‘Beyond The Pale’, a Hindu proverb: Love heeds not caste nor sleep a broken bed, I went in search of love and lost myself. And whether or not the object letter was something Kipling ever encountered, the incident in his fictional story resembles one later mentioned in historian IJ Gelb’s A Study of Writing (1952). Gelb refers to a package sent from a young woman in Eastern Turkestan to her lover. It contained a message in the form of a lump of tea, a leaf of grass, a red fruit, a dried apricot, a piece of coal, a flower, some sugar, a pebble, a falcon’s feather and a nut. It was intended, says Gelb, to be read as follows: ‘I can no longer drink tea, I’m as pale as grass without you, I blush to think of you, my heart burns as coal, you are beautiful as a flower, and sweet as sugar, but is your heart of stone? I’d fly to you if I had wings, I am yours like a nut in your hand.’[46]

The term ‘object language’ also refers to language as a thing, an object in itself and something that can be broken into many other constitutive parts. All language exists in relation to physical objects, from a body’s first messages of love and pain, to an acceptance of the material world around us as something processed and parcelled up in a typography of weights, measures and formats. The study of language in the 1800s is characterised by a historical comparative method, an evolutionist search for origins with a clear preference for language that can’t talk back. By the twentieth century, the focus shifts to language as a living system, the human implications of its social uses and the relationship between language and thinking. The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure provides a stimulating connection between the old and the new. As a nineteenth century student of philology, he proposed a theory of ghost phonemes surviving in the recesses of the human mouth. Reaching back to its fossilised origins he discovers a live signal. Yet in his influential Course in General Linguistics (1916), de Saussure talks about language as an imperialist might describe the wordless wastes of the colonial world – ‘thought is like a swirling cloud’, he says, ‘where no shape is intrinsically determined. No ideas are established in advance, and nothing is distinct before the introduction of linguistic structure’.[47]

If this was a relationship that Saussure took for granted, others after him have investigated what it means to be thought by language, focusing on the system itself. Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, students of Franz Boas and therefore associated with the rise of the anthropologist-linguist, followed language through its functional basis – a socially contextualised use of language that begins with discourse. The object letter of Kipling’s story is language slowed down to reveal many of its registers and stages occurring together: linguistic and non-linguistic, textual and contextual, ideational and interpersonal. This is language in its indexical mode, mapping out bodies, places and time as components of the exchange: a package of things, a collection of objects transferred between persons, symbolic and with equivalence-based associations, making connections both physical and illicit. The loss or absence of a referent in what we might think of more conventionally as writing is also marked here – in the devastating cruelty of Bisesa’s punishment, and directed to the story’s intended, and predominantly white male, audience by Trejago’s emasculating wound.

Uniforms that haunt us while we sleep

Christina Broom, Kit of an Irish Guardsman laid out for inspection, c. 1914, Imperial War Museum.

For kit-inspection, British soldiers are required to make a precise formal presentation of their uniforms, equipment and bedding. These have often been photographed for reference, appearing in manuals or on the wall of a barrack block. I first saw this photograph by Christina Broom in Val Williams’ significant book Women Photographers.[48] Born in London, Broom was Britain’s first female press photographer and from 1904 until her death in 1939 the official photographer to the Royal Household Guards. Williams responds to the photograph’s uncanny sense of presence: ‘the ends of a cane laid beneath each thumb of a pair of gloves and the exact positioning of a pair of boots’.[49] A ghostliness, along with the careful assembly of fabric and tools, and the great pin-like cane, that reminds me of Bond’s ostrich photo.It also makes me think of the episode in HG Welles’ Invisible Man (1897) when Griffin falls asleep in the bedding section of a department store after draping his invisible self in gloves and socks, trousers, vest, jacket and hat.

For many years, Broom was assisted by her daughter Winifred. In a 1971 memoir about her mother’s work, Winifred Broom recalls their first meeting with Lord Roberts, a former British Army commander-in-chief and a colonel of the Irish Guards. Roberts commended Broom for her postcard prints, which soldiers bought to send home to their families: ‘I have prayed for recruits for the 3rd Scots and the Irish Guards [and] these two women have shown us the way – I shall tell the King!’[50] When his son John failed the medical examinations with poor eyesight, Kipling wrote to his friend, the same Lord Roberts, and John was accepted into the Irish Guards. He died on the second day of the Battle of Loos, September 1915.

The Irish Guards were founded in 1900 by order of Queen Victoria to commemorate the Irishmen who fought in the Boer War on the side of the Empire. After World War I, Kipling wrote a two-volume history of his son’s regiment and their service in the war. His most successful and popular novel Kim, published in 1901, is focused around the son of an Irish soldier from a fictional Irish Regiment known as The Mavericks, Her Majesty's Royal Loyal Musketeers.

Kipling was the historian of those now forgotten Irish who were loyal to the Empire, articulating in his writing a dream of empire, almost a masterful dream-work of condensation, with its colonies, different from each other in history, culture and language, threaded together into one vision, solely by virtue of their belonging to the Empire.[51]

At the centre of this dream is Kim ‘an imperial boy who is at once Irish and Indian’, a metaphor for imperial unity. ‘The dream was a chimera, masking the violence and abuses of the empire, but Kipling, in his day and after, was its most effective propagandist.’[52]

Kipling’s fascination for language provides a theme in his work that achieves exceptional focus in Kim. Influenced by Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, the novel centres on a pair of characters traveling across a large country in an atmosphere of youthful adventure. But written as an intricate web of literary double-agency it is also a cold-war spy thriller.It tells the story of British military intelligence gathering in Tibet and India in a colonial bid to resist Indian nationalists and the rival imperialism of Russia. The novel features a spectacular diversity of language, mainly because Kim is being trained to think of language as a bodily medium through which intelligence is gathered. Like Kipling, Kim is born in India in 1865. An Irish regimental son, he lives on the street and prefers the look and language of a low-caste Hindu boy. Using other dialects and costumes, he is able to switch identity across the spectrum of Indian social life. From Mohammedan oilman to Oudh landholder, he carefully perfects the nuanced ways of each caste, how they ‘talked, or walked, or coughed or spat, or sneezed’.[53] In Midnight’s Children (1981), Salman Rushdie seems to wink at Kim through the character of Saleem Padma. An ancient prostitute, she claims to be 512, and possesses ‘a mastery over her glands so total that she could alter her bodily odours to match those of anyone on earth’.[54]

By the end of his story, Kim has reached the weather-beaten age of seventeen, and is already beyond the art of disguises. Under the shape-shifting sign of language, he is also a master of identities. In various ways, so are his teachers and fellow spies. All of the prominent characters in Kim are British agents involved in the so-called Great Game, a political and diplomatic confrontation, a cold war that prevailed for most of the nineteenth century between Britain and Russia.

Kim memorises whole chapters of the Koran by heart, ‘till he could deliver them with the very role and cadence of a mullah’.[55] At the same time he is trained as a pundit in the art and science of mensuration – the geometry of lengths and volumes, acquired by ‘marching over a country with a compass, a level and a straight eye […] a boy would do well to know the precise length of his foot pace and to keep count of thousands of paces [using] nothing more valuable than a rosary of eighty one or a hundred and eight beads’.[56] Mimicking the body movements of others, including animals, he is described variously as moving ‘silently as a cat’ and as ‘softly as a bat’, when, ‘being lithe and inconspicuous, he carried out commissions by night on the crowded housetops.’[57] He encounters ‘a talking Mynah […] which has picked up the very tone of the family priest’[58] and later, in the mountains, Kim listens to ‘the trackers and shikarris of the Northern valleys’, Himalayan hill-folk who cry messages to each other as they move with their animals: ‘from the edge of the sheep-pasture, fifteen hundred feet above, floated a shrill kite-like trill. A child tending cattle had picked it up from a brother or sister on the far side of the slope that commanded Chini valley.’[59]

Historical figures whose reputations and work in India are built into the context and storyline of Kim, include Colonel Thomas Holdich (1843–1929), author of Political Frontiers and Boundary Making, and better known as Superintendent of Frontier Surveys in British India, as well as Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Montgomerie (1830–1878), the Royal Engineers officer who disguised his surveyors as monks after becoming aware that Indian natives were able to pass freely across the Tibetan border. In 1862, he trained the first of a series of Hindu pundits carrying concealed equipment in robes lined with secret pockets, adapting local practices, and using modified Buddhist rosary beads as decimal abacuses. Montgomerie‘s programme of covert surveillance was conducted under the joint auspices of the India Survey and the British Museum, and culminated in Britain’s occupation of Tibet in 1903. A third figure is Arthur Conolly (1807–1842), a British intelligence officer who coined the term ‘The Great Game’. Conolly was executed in 1842 by the Emir of Bukhara on charges of spying for the British Empire.

Thomas Richards, author of The Imperial Archive (1993) shows how an Orientalist obsession with language and comprehensive knowledge joined other science-based fields – biology, geography and geology – to help manage and organise Britain’s imperial deposits. An Empire that seems to have gained its momentum from what Richards describes as the ‘peculiarly Victorian confidence that knowledge could be controlled and controlling’[60] was now an immense and failing administrative challenge. Knowledge-producing institutions like the British Museum, The Royal Geographical Society, the India Survey and the universities were enlisted to establish a fantasy model for an empire maintained not by force but information. Surveying, mapping, gathering statistics and data, organising it across ledgers, charts and archives as if that could somehow hold the fragmented parts together. As an accumulative fiction, however, the British Empire was far more easily managed in the form of a novel such as Kim.

As self-appointed allegorist of Empire, Kipling’s writing serves his own purposes, whether taking the form of a fable, a mythical saga, or a novel-length children’s adventure story. His Indian stories are inflected with phrases from local languages and dialects. Gujarati language poetHarish Trivedi describes how Kipling’s reputation as a writer with exceptional insider knowledge about India was made more convincing by his casually deceptive and often incorrect use of vernacular terms and phrases. Kipling follows a similar approach with British dialects, though these are based in his own first language of English. The following example, an Irish soldier Mulvaney speaking in the short story ‘The Three Musketeers’, is a combination of both, turning, as Trivedi observes, Kipling’s limited stock of misunderstood Hindustani ‘into a comic virtue’:

I purshued a hekka, an’ I sez to the dhriver-divil, I sez, ‘Ye black limb, there's a Sahib comin’ for this hekka. He wants to go jildi to the Padsahi Jhil’ – ‘twas about tu moiles away – ‘to shoot snipe–chirria. You dhrive Jehannum ke marfik, mallum–like Hell? ‘Tis no manner av use bukkin’ to the Sahib, bekaze he doesn’t samjao your talk. Av he bolos anything, just you choop and chel. Dekker? Go arsty for the first arder–mile from cantonmints. Thin chel, Shaitan ke marfik, an’ the chooper you choops an’ the jildier you chels the better kooshy will that Sahib be; an’ here’s a rupee for ye?’[61]

To some, Kipling’s mimicry of languages seems vulgar and populist, to others it shows an inventiveness that anticipates the modernism of Joyce and Eliot. For Jan Montefiore, the approximation to ordinary speech, in both ‘the imagined language of Indians’ and the actual demotic of a coarsely accentuated Irish soldier – ‘allows his fiction to handle racial and class difference with a degree of ease and intimacy’.[62] Yet Kipling’s relationship to Ireland was as ideological as his feelings about India. Aggressively opposed to Irish Home Rule, by 1914 he was calling for civil war and channelling his language skills into writing songs for the volunteers.

In Kipling’s Just So Stories, written for his daughter Josephine, we learn ‘How The First Letter Was Written’, and ‘How The Alphabet Was Made’. Combining foundational myths with a colonial British sense of manifest destiny, the Roman alphabet emerges fully formed in rune-like letters derived from the shape of objects and living creatures (a carp’s mouth for an A, a fish tail for a Y, a snake for an S), scratched into bark with a shark’s tooth by Taffy and her father Tegumai.

‘Shu-ya-las-ya-maru,’ said Taffy, reading it out sound by sound. ‘That’s enough for today,’ said Tegumai … ‘We’ll finish it tomorrow, and then we’ll be remembered for years and years after the biggest trees you can see are all chopped up for firewood.’[63]

Later, after the completion of ‘the fine old easy, understandable Alphabet – A, B, C, D, E, and the rest of ‘em’, Taffy and her father spend ‘five whole years’ on a magic Alphabet-necklace of black-mussel pearls, beads of amber, clay, glass, silver and gold, rough lumps of copper, turquoise, stone, soft iron and flat pieces of ivory all strung together on a length of reindeer sinew. Between each bead or material specimen is a letter, either scratched into a clay token or improvised from an object: ‘E is a twist of silver wire … O is a piece of oyster shell with a hole in the middle … T is the end of a small bone.’[64]

How was the first letter written? It is now generally agreed that writing was invented in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, in the late fourth millennium BC, and spread from there to Egypt, Elam and the Indus Valley. The idea that Mesopotamian writing emerged from collections of objects is new. For thousands of years the origin of writing was the subject of myths crediting heroic gods and fabulous creatures with its invention. By the eighteenth century it was believed to have begun with picture writing. But the immediate precursor of cuneiform writing was a system of tokens: small clay objects of many shapes – cones, spheres, disks, cylinders – that served as counters and can be traced to the Neolithic period, starting around 8000 BC. They evolved to meet the needs of the economy, at first keeping track of the products of farming. Excavated in the 1920s from Nuzi in Northern Iraq, a hollow tablet together with a flat tablet bearing an account of the same transaction were discovered in the family archive of a sheep owner named Puhisenni. The cuneiform inscription on the hollow tablet read as follows: ‘Counters representing small cattle: 21 ewes that lamb; 6 female lambs, 8 full grown male sheep; 4 male lambs; 6 she-goats that kid; 1 he-goat; 3 female kids’,[65] and was signed with the seal of a shepherd named Ziqarru. When opening the hollow tablet, the excavators found it to hold forty-nine counters, which, as stipulated in the text, corresponded to the number of animals listed.[66]

The first letter may have been a clay counter. Listing, a frequent trope of Kipling’s stories, is also anobject language; aform of metonymic realism that conveys the world through the itemizing of things in it, as when the character Morrowbie Jukes makes his methodical inventory of the contents of a mummified English soldier’s pockets. “The list suggests meaning even if it withholds it” writes Nora Crook in her assessment of Kipling’s story.[67] Like the objects in Bond’s ostrich photograph, the collection of personal effects pulled from the soldier’s body are broken, worn out and indecipherable fragments:

I give the full list in the hope that it may lead to the identification of the unfortunate man: 1. Bowl of a briarwood pipe, serrated at the edge; much worn and blackened; bound with string at the crew. 2. Two patent-lever keys; wards of both broken. 3. Tortoise-shell-handled penknife, silver or nickel, name-plate, marked with monogram “B.K.” 4. Envelope, postmark undecipherable, bearing a Victorian stamp, addressed to “Miss Mon —” (rest illegible)—“ham”—“nt.” 5. Imitation crocodile-skin notebook with pencil. First forty-five pages blank; four and a half illegible; fifteen others filled with private memoranda relating chiefly to three persons—a Mrs. L Singleton, abbreviated several times to “Lot Single,” “Mrs. S. May,” and “Garmison,” referred to in places as “Jerry” or “Jack.” 6. Handle of small-sized hunting-knife. Blade snapped short. Buck’s horn, diamond cut, with swivel and ring on the butt; fragment of cotton cord attached.[68]

Language mediated as a collection of objects features early in Kipling’s autobiography. ‘When my father sent me a Robinson Crusoe with steel engravings I set up a business alone as a trader with savages (…). My apparatus was a coconut shell strung on a red cord, a tin trunk and piece of packing-case which kept off any other world.’ In other words it also conjured a private zone of reality: ‘Thus fenced about, everything inside the fence was quite real, but mixed with the smell of damp cupboards.’[69]

Another book that impacted on Kipling’s childhood reading is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), a tale of adventure that merges early colonial voyages with the anarchy of piracy. In a famous passage Billy Bones’ sea chest holds a tantalising message of exotic plunder when Jim Hawkins breaks it open and takes stock:

“…a quadrant, a tin canikin, several sticks of tobacco, two brace of very handsome pistols, a piece of bar silver, an old Spanish watch and some other trinkets of little value and mostly of foreign make, a pair of compasses mounted with brass, and five or six curious West Indian shells (…) and a canvas bag, that gave forth, at a touch, the jingle of gold."[70]

Above all, Empire is about financial profit and the establishing or claiming of value. In F. W. Bond’s ostrich photograph, the worthless looking objects are clearly one half of an unequal trading deal. Reminiscent of stories like that of the Tierra del Fuegian boy Jemmy Button, bought, and so named in 1830 by Captain Robert Fitzroy for a handful of mother-of-pearl buttons. F. W. Bond, a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, was born in 1887 and died in 1942. The RPS Journal’s obituary for Bond, celebrating his work as a photographer, reminds the reader that for many years “Mr Bond occupied the responsible post of Assistant Treasurer to the Zoological Society of London.” Bond was employed at the zoo as an accountant. It was in the service of accountancy that writing was invented. Appropriately then, Bond has arranged the ostrich tokens as cleanly as printing forms in a sixteenth century typesetter’s case. Lead castings of Roman capitals, ligatures, fleurons and punctuation have been replaced with symbols of a lower status: bent hooks, torn fabrics, a few copper coins and some old rope. Like the alphabet, they still mirror the collective form of society, but unlike typographical letters, the pieces don’t match up or form a collective whole. The only working part of the puzzle is the deadly function of the nail. Such signs of excess and collapse, essential to any understanding of how our world attempts to function, could not have been lost on F. W. Bond. What could express the accumulations of an imperial nation better than a few tired examples of its debris? In this case spelling out the grim memento of a once regal bird with a typography of rubble.[71]

The Jungle Book (1893) and Just So Stories (1912) are written as animal fables. In ‘Mowgli’s Brothers’ Kipling turns the wild animals into ‘Jungle People’, granting them speech, individuality, the conversation of men. The earliest fables are believed to be Mesopotamian, and the tradition is that animal life is replaced by an index of human characteristics, offering moral guidance indirectly to individuals, family and community. The stomach of Bond’s ostrich has also been replaced by parts of clothing, tools, coins and other human effects. Both Aesop and the Roman fable writer Phaedrus were former slaves, and Greco-Roman fables are often interpreted as the voice of oppressed human classes. Marianne Moore’s animal vision is similarly focused on unpopular or disregarded species, the hedge sparrow, for example, in ‘Virginia Britannica’, ‘that wakes up seven minutes sooner than the lark’ – or it did in 1934, when wake-up times were recorded across Britain during an all-night ramble of the British Empire Naturalists’ Association (BENA). Moore may have included this poem as a nudge to Shelley’s grand skylark. It also offers a glimpse of a nation’s post-imperial imagination, keeping a check on its migrant avian workforce. BENA had been founded in 1905 by Edward Kay Robinson, who, as editor of the Civil and Military Gazette in Lahore, supported Kipling’s earliest published writing. The son of an East India Company chaplain, Kay Robinson, was born in Naini Tal, a Kumaon hill station in the outer Himalayas. Kay Robinson championed the photography of animals over their collection for museums and zoos, at least partly connecting his interests to those of FW Bond, whose photographs he would have been aware of.

Moore wrote at least 40 poems featuring animal subjects from ‘A Jelly-fish’ in 1909 to ‘Tippoo’s Tiger’ in 1967 and referred to them as her ‘animiles’, ‘pertaining to animals … an echo of something like “Anglophiles.” The form of affinity’. If her poems are fable-like without the animals speaking as humans, there is one unforgettable exception in a poem called ‘The Monkeys’. It is the only occasion on which Moore invokes a visit to the zoo, where the animals appear faded, humdrum and abnormal. Fed in their cages, they are like prisoners in a concentration camp. Suddenly a cat, with resolute tail, ‘that Gilgamesh among the hairy carnivore’, addresses both visitor and reader. It is a startling moment, equivalent in pathos and acerbic anger to the creature’s monologue in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The cat declares the ultimate indignity of being imprisoned by a society

strict with tension, malignant

in its power over us and deeper

than the sea when it proffers flattery in exchange for hemp,

rye, flax, horses, platinum, timber and fur.[72]

The cataloguing of natural features of the world – minerals, plants and animals – is a recurring motif in Moore’s poetry. But here the poem ends as a list of materials – the plunder of empire – and the final word, fur, reducing the creature to a commodity listed among other by-products of industrial/commercial human culture as mere items on an inventory sheet.

[1] Marianne Moore, “He “Digesteth Harde Yron”, in What Are Years (New York: Macmillan, 1941).

[2] Golden Days, Historic Photographs of the London Zoo (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd 1976).

[3] Alexander Macalister, ‘On the Anatomy of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus)’,

Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836-1869), Vol. 9 (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1864–66), pp. 1–24.

[4] Macalister, ‘On the Anatomy’, p. 3.

[5] Gustave Flaubert, Dictionary of Accepted Ideas (New York New Directions, 1968).

[6] Macalister ‘On the Anatomy’, p. 2.

[7] William Shakespeare, King Henry VI, Second Part, Act IV, Scene X.

[8] Pliny, Naturalis historia (Ancient Rome AD77–79).

[9] Henry VI, Act IV, scene X.

[10] The Family Magazine, Vol. 1, 1835, p. 210.

[11] Harold Bloom, ‘Marianne Moore, 1887–1972’, in Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 20th Anniversary Collection, Poets and Poems (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2005), p. 286.

[12] Harold Bloom, Marianne Moore (New York: Chelsea House, 1987), p. 3.

[13] ‘About One of Marianne Moore’s Poems’, in Wallace Stevens, The Necessary Angel (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1951), p. 94.

[14] Una Roman De’Elia, Raphael’s Ostrich (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Job 39:13–19.

[17] George Jennison, Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome (Manchester University Press, 1937).

[18] John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’, in Selected Essays (New York: Vintage International, 2003), p. 261.

[19] Marianne Moore, ‘The Jerboa’, first published in 1932.

[20] Willene B. Clark, A Medieval Book of Beasts (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2013), p. 18.

[21] Thomas Allsen, The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), p. 10.

[22] David Hancocks, ‘So Long, Old Zoo, in BBC Wildlife, June 1991, p. 424.

[23] Randy Malamund, Reading Zoos (New York: NYU Press, 1998).

[24] Robert H MacDonald,The Language of Empire: Myths and Metaphors of Popular Imperialism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), p. 3.

[25] Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1902) (London: Penguin, 1973).

[26] George Orwell, Shooting an Elephant (1936) in The Penguin Essays of George Orwell (London: Penguin, 1994), pp. 18–25.

[27] DH Lawrence, ‘Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine’ (1925), in Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1988) pp. 349–63.

[28] Orwell, 1936.

[29] Marianne Moore, ‘Apparition of Splendor’ (first published in The Nation 175, October 1952).

[30] Marianne Moore, ‘Elephants’ (first published in The New Republic 109, 23 August 1943).

[31] See Massin, Letter and Image (Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1970), p. 67.

[32] Marianne Moore, ‘Virginia Britannia’, first published in Life and Letters Today, 13 December 1935.

[33] Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978).

[34] Edward William Lane, An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1860), p. 213.

[35] Ibid, p. 325.

[36] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 1983), p. 70.

[37] Ibid, p. 46.

[38] Harold Innis, Empire and Communications (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1950).

[39] Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (London: Vintage, 1994), p. xiii.

[40] Rudyard Kipling, ‘Beyond the Pale’, in Plain Tales From the Hills (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Company, 1888).

[41] Rudyard Kipling, Something of Myself (1937)(Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 33.

[42] Kipling, ‘Beyond the Pale’.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Sara Suleri, The Rhetoric of English India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 112.

[46] IJ Gelb, A Study of Writing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969).

[47] Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), p. 110.

[48] Val Williams, Women Photographers (London: Virago 1986).

[49] Ibid.

[50] Winifred Broom’s privately published 1971 memoir is quoted in Anna Sparham, Soldiers and Suffragettes: The Photography of Christina Broom (London: Philip Wilson, 2015), p. 87.

[51] Kaori Nagai, Empire of Analogies: Kipling, India and Ireland (Cork University Press, 2006).

[52] Ibid.

[53] Rudyard Kipling, Kim (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Libraries), p. 252.

[54] Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children (London: Vintage, 2011), p 319.

[55] Kipling, Kim, p. 269.

[56] Ibid., p. 258.

[57] Ibid., p. 4.

[58] Ibid., 344.

[59] Ibid., p. 409.

[60] Thomas Richards, The Imperial Archive (London: Verso, 1993), p. 7.

[61] http://www.online-literature.com/kipling/3792/ (accessed July 2018).

[62] Jan Montefiore, ‘Imagining a Language’, in Jan Montefiore, Rudyard Kipling (New Delhi, North Cote House Publishers, 2007), p. 32.

[63] Rudyard Kipling, ‘Just So Stories: How the First letter was Written, in The Complete Children’s Short Stories (Herfordshire: Wordsworth Editions, 2004), p. 336.

[64] Ibid, p. 338.

[65] Rudyard Kipling, ‘To be Filed for Reference’, in Plain Tales from the Hills (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Company, 1888), p. 247.

[66] See Denise Schmandt-Besserat, How Writing Came About; From Counting to Cuneiform (Austin: University of Texas, 1996), p. 9.

[67] Nora Crook, Kipling’s Myths of Love and Death (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), p. 103.

[68] Rudyard Kipling, ‘The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes’, Collected Stories (Middlesex: Penguin 1994).

[69] Rudyard Kipling, Something Of Myself (Middlesex: Penguin 1987).

[70] Robert Louis Stevenson, Treasure Island (London: Penguin, 1999).

[71] The Photographic Journal, RPS (London, May 1942), p. 210.

[72] Marianne Moore, ‘The Monkeys’, first published in 1917.

Download this article as PDF

Paul Elliman

Paul Elliman (UK) lives and works in London. His work follows language through many of its social and technological guises, in which typography, human voice, and bodily gestures emerge as part of a direct correspondence with other visible forms and sounds of the city. Elliman is a visiting tutor for the MFA Voice Studies programme at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. He has exhibited widely in venues such as the ICA, London, UK (2014); New Museum, New York, USA (2008); Tate Modern, London, UK (2001); and MoMA, New York, USA (2012); with recent solo exhibitions at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany (2017) and La Salle de Bains, Lyon, France (2017).

- Notes on Design & Empire

Joasia Krysa - Learning from Liverpool: An Introduction

Emily King and Prem Krishnamurthy - Empire Remains Christmas Pudding

Cooking Sections - Contents of Ostrich’s Stomach

Paul Elliman - Brown is the New Green

Mae-ling Lokko - Designing Brazil Today

Frederico Duarte - UTOPIA and the Metainterface

Christian Ulrik Andersen - Colophon