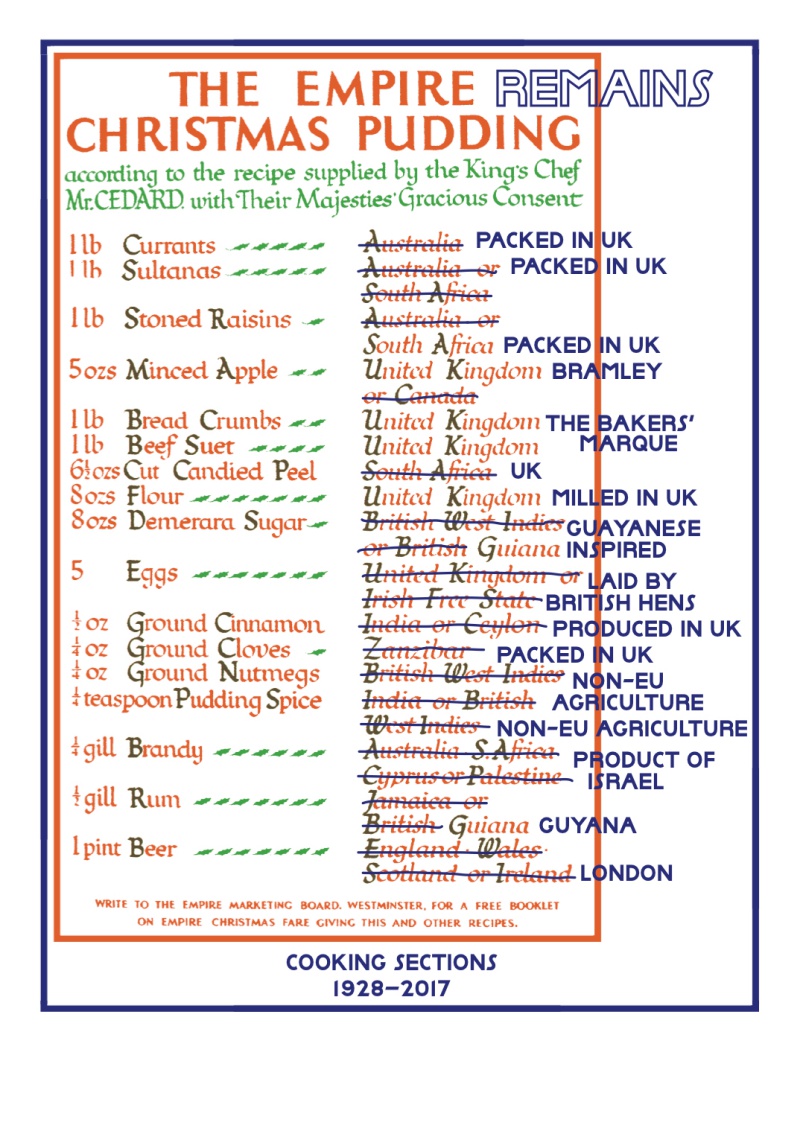

Empire Remains Christmas Pudding

Cooking Sections

Empire Remains Christmas Pudding, Cooking Sections (2013-...). Image by Cooking Sections.

Empire Remains Christmas Pudding, Cooking Sections (2013-...). Image by Cooking Sections.

The Empire Remains Shop project began with the recipe for an Empire Christmas Pudding, a well-known ‘gastronomic paradox’: the most English of dishes made from the most un-English of ingredients.[1] Invented in 1928 by King George V’s chef André Cédard, the dish is composed of seventeen ingredients from seventeen different places of origin: currants from Australia, raisins from South Africa, cinnamon from India, cloves from Zanzibar, apples from Canada... More than a recipe, the list of ingredients operates like a map. The Empire Remains Christmas Pudding is the first project developed for The Empire Remains Shop. It traces the changes in the postcolonial food market by exploring the economic strategies and forces at play today. Every Christmas since 2013, we have tried to source the same ingredients with the same origins from supermarkets in London. (Follow the recipe included below to make your own.)

The Empire Remains Christmas Pudding makes evident that if foodstuffs were once promoted according to their source, today they are are rather ‘packed in the UK’, ‘milled in the UK’, ‘produced in the EU’ or use ‘sugar from a range of countries’. New economies of origin do not promote a sense of place, but the erasure of it. In some cases, particularly for dried fruits, it is more economical to simply change the supplier according to national conflicts, weather events, etc., without telling customers. The regulatory shift in the 1990s gave supermarkets control over sourcing, distribution, packaging and marketing, allowing them to supersede traditional geographies and sovereign powers.[2] Within the context of post-Brexit anxiety over supply shortages of Southern European vegetables, big chains have reinvented the ‘local/national’ by disguising internationally variable bulk produce through branding for fictional, British-sounding farms.[3] The trust consumers put in brands encourages a lack of transparency, but the dissolution of origins produces a contemporary logic that has shifted from ‘Made In …’ to ‘Made Nowhere’.

Commercial relationships between European nations and former colonies indicate the radically different approaches to trading that exist today. French neocolonial schemes in West Africa have mobilised peasant cooperatives, while supermarket standards for exchange between East African countries and Britain have encouraged expatriate scams.[4] In the case of Guyana (formerly British Guiana), profitable sugar-cane fields along the banks of the Demerara River are associated with uniquely sweet golden crystals. Today, however, brown sugar is branded by Tate & Lyle as ‘Guyanese-inspired’ instead of ‘from Demerara’. Guyanese sugar is included when fluctuations in global pricing are convenient; at other times, ‘Demerara-inspired’ will suffice. In such cases, place is only important when it evokes a ‘glorious’ landscape from the past – as happens in the marketing of Caribbean rum with images of lushness, hedonism and piracy.

[1] Kaori O’Connor, ‘The King's Christmas Pudding: Globalization, Recipes, and the Commodities of Empire’, Journal of Global History, vol. 4, no. 1 (March 2009), pp. 127–55.

[2] Susanne Freidberg, ‘Supermarkets and Imperial Knowledge’, Journal Title?, June 2007l, pp. 321–42.

[3] The ‘fake farm’ branding strategy uses rural, historic or natural references to reassure shoppers of the original quality of internationally sourced bulk produce: Nightingale Farms (for Spanish and Moroccan tomatoes), Suntrail Farms (for imported oranges, lemons, and avocados) or Woodside Farms (for German, Dutch or Danish pork). Indeed, Woodside Farm does exist somewhere in Britain, but its real owner is suing Tesco for appropriating the name of his farm without sourcing produce from him.

[4] Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 65; Susanne Freidberg, French Beans and Food Scares: Culture and Commerce in an Anxious Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Download this article as PDF

Cooking Sections

Cooking Sections (Daniel Fernández Pascual, Spain & Alon Schwabe, Israel) live and work in London. A duo of spatial practitioners, Cooking Sections was founded in 2013. It was born to explore the systems that organise the world through food. Using installation, performance, mapping, and video, their research-based practice explores the overlapping boundaries between visual arts, architecture, and geopolitics. Cooking Sections was part of the exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion, Venice Architecture Biennale, Italy (2014). Their work has also been exhibited at the 13th Sharjah Biennial, United Arab Emirates (2017); Storefront for Art & Architecture New York, USA; dOCUMENTA 13, Germany (2012); Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy (2014); CA2M, Madrid, Spain (2015); The New Institute, Rotterdam, Netherlands (2016); UTS, Sydney, Australia (2016); and the Oslo Architecture Triennale, Norway (2016). They have been residents in The Politics of Food at Delfina Foundation, London, UK, and currently lead a studio unit at RCA, London, UK. In 2016 they opened The Empire Remains Shop.

- Notes on Design & Empire

Joasia Krysa - Learning from Liverpool: An Introduction

Emily King and Prem Krishnamurthy - Empire Remains Christmas Pudding

Cooking Sections - Contents of Ostrich’s Stomach

Paul Elliman - Brown is the New Green

Mae-ling Lokko - Designing Brazil Today

Frederico Duarte - UTOPIA and the Metainterface

Christian Ulrik Andersen - Colophon