Interview with Slavs and Tatars

Deena Chalabi

Deena Chalabi: Slavs and Tatars’ work emphasises overlooked cultural and historical complexities, and with Future City we’ve been curious about how those might enrich our current and future thinking. So, what do you believe should be remembered or forgotten?

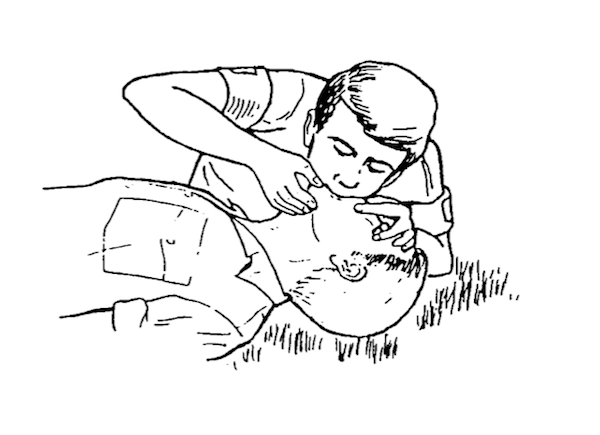

Slavs and Tatars: In lieu of what, let’s rather turn to how we should remember or forget. We believe in resuscitating history, and we use this word ‘resuscitation’ deliberately: putting one’s lips onto the subject matter, onto history, onto language, and breathing in and out of it. So there’s a sensual, seductive element to the revisitation, a corporal approach. There’s also something disrespectful about this act of resuscitation: putting one’s lips onto another's to revive him/her is different from placing one’s lips on someone else’s romantically, as in a kiss. It’s just as important to disrespect your sources as it is to respect them.

"Pucker up, History" Slide from TransliterativeTease, lecture-performance, 51 min, 2013.

DC: Speaking of sources, Slavs and Tatars began as a reading group for out-of-print works, or texts unavailable in English, and original publications have a very important function in your practice. Have you always seen your work in terms of a process of reactivating cultural memory and/or a quest for alternative historical narratives?

S&T: We’ve attempted to reactivate certain ideas, behaviours, affects and thought-processes associated with a given geographical region. 1 To some degree, we see this work as a correction: recalibrating the balance, whether it involves acknowledging the progressive potential of faith in social revolutions, the sacred use of language, the collective acts of reading and storytelling, for example.

Slavs and Tatars' publications, 2009-2013.

Slavs and Tatars' publications, 2009-2013.

DC: How important is storytelling for creating a sense of place?

S&T: The oral aspect of storytelling is crucial to an understanding of place. Despite our extensive publication output, we retain a healthy suspicion of print. In her research on Byzantine music, Bissera Pintcheva talks about the meaning of icons understood as performance: ‘a descent and dwelling of spirit in matter’. Through its oral iteration, each story becomes a practice in genealogy, akin to the hadiths.

DC: So what’s at stake in the process of retelling certain lost narratives, or bringing ideas back into circulation? What kinds of tensions do you see embedded in the practice of making things visible?

S&T: Creating visibility is itself a two-fold risk. First, it’s not enough to excavate a given narrative or idea; one also needs to activate it. Second, in a world with increasingly immediate access to information and demands for transparency, it’s also imperative for some things to remain imperceptible. As Norman Brown said, ‘Mysteries are intrinsically esoteric, and as such are an offense to democracy: is not publicity a democratic principle?’

DC: Different parts of the world have different legacies in terms of the relationship between the individual and the society, which create different expectations and conceptions of the public. Your works often play off these various legacies. How do you engage with how we might live collectively?

S&T: Our work often operates along the lines of a bazaar or souk: there’s a fanning out of media, a something-for-everyone approach that runs counter to the stern rarefaction we associate with modern and contemporary art. Our Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, for example, tells the story of twenty-first-century Iran through that of 1980s Poland and Solidarno??. The project began as a magazine contribution (to the Berlin-based biannual 032c), a public balloon, an archive, textile works, public billboards, lectures, publications, mirror mosaics and craft-specific sculptures. Stemming perhaps from our regional focus, this maximalism allows the audience different levels of entry into the project. And this not-only-but-also approach requires us to engage with the notion of generosity, to face our audience, as opposed to making work that could remain insular or only relevant to an art professional. It acknowledges different interests, needs and people.

Pray Way (installation view), slim and wool carpet, MDF, steel, neon. 390 x 280 x50 cm, 2012. The Ungovernables 2nd New York Museum Triennial, New York. Photo courtesy of Patrick McMullan.

Pray Way (installation view), slim and wool carpet, MDF, steel, neon. 390 x 280 x50 cm, 2012. The Ungovernables 2nd New York Museum Triennial, New York. Photo courtesy of Patrick McMullan.

If a visitor to one of our installations – whether Beyonsense at MoMA , PrayWay at MoMA Warsaw, or Not Moscow Not Mecca at the Vienna Secession – simply sits down and caresses his/her partner, that’s an equally legitimate engagement with the work as that of someone who might have read everything available on line and peruses our books in the exhibition space. This lack of ‘preciousness’ about our work comes from our interest in reconsidering notions of generosity and sacred hospitality: for example, linguistic hospitality, expropriating ourselves and appropriating the other as we attempt to put on the clothes of the foreign and ask the foreign to step into our language.

DC: In addition to your linguistic agility, your practice is also predicated on dismantling the rhetoric of (increasingly defunct) imagined geographies. Does unearthing forgotten examples of syncretism help to imagine a different kind of cosmopolitan future?

S&T: Syncretism is to the mind what open-source is to code: it allows for the integration of 'alien' or 'other' forms of thought, behaviour, practice into one's own. It also operates a collapse of time, not just of space, allowing for the incorporation of those beliefs that precede one's own. We should highlight the numinous or 'wholly other', to quote Rudolf Otto, context in which syncretism is often used: by reconciling difference and emphasising coexistence, syncretism is a compelling argument in favour of compromise too often disparaged as a source of weakness.

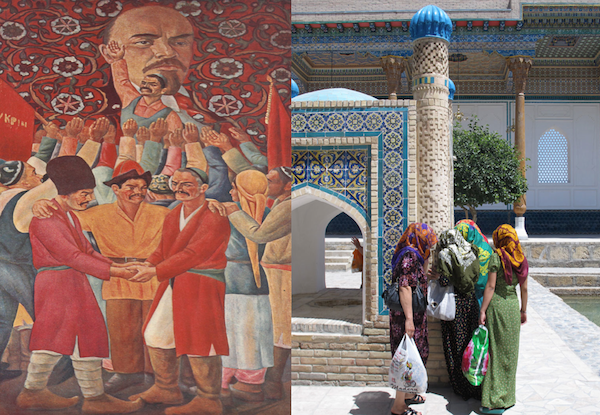

Left: The Triumph of Leninist-Stalinist National Politics, by N.

Narakhan, 10 Years of Soviet Uzbekistan),

1934, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, NY. Right: Women at the

shrine of Naqshbandi, outside Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

Left: The Triumph of Leninist-Stalinist National Politics, by N.

Narakhan, 10 Years of Soviet Uzbekistan),

1934, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, NY. Right: Women at the

shrine of Naqshbandi, outside Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

DC: Have your adventures in Eurasian archives yielded any surprising notions of utopia, whether fictional or theoretical? Is there something emancipatory about the process of reclamation?

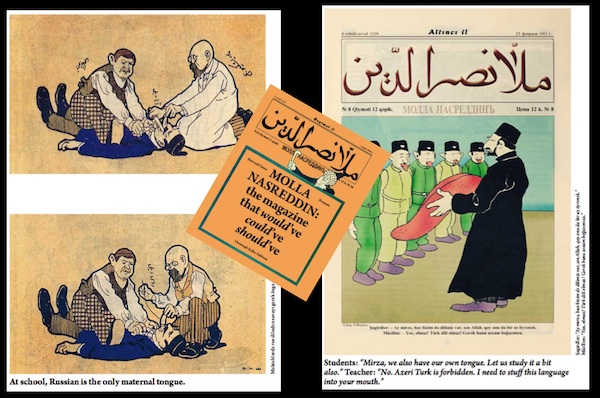

S&T: It has often been in engaging with archives or material whose position is antithetical to ours where we’ve experienced something resembling liberation. Molla Nasreddin,2 the early twentieth-century Azeri political satirical magazine that we translated in 2011, for example, argued for modernisation as westernisation and blamed Islam for what it considered the increasing gap between the Western world and the Muslim world, both ideas that stand in opposition to the very founding of our practice. In this sense, Molla Nasreddin was very much a product of its time, like Atatürk’s Dil Devrimi (language reforms). Rarely do artists, writers, or others devote two years to translating and publishing a document with which they strongly disagree.

Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would've, could've, should've (JRP-Ringier, 2011).

Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would've, could've, should've (JRP-Ringier, 2011).

DC: In Long Legged Linguistics, the works address a set of issues that one might describe in terms of politicised, embodied language. How does your recent set of works speak to the process of making or unmaking citizenship through language?

S&T: Our approach to identity is to adopt several at once – hence our name – not to mention our interest in the transmogrification of ideas across various cultures, landscapes, people. It’s a pity that allegiances in general are conceived as singular, exclusive affairs. Since the end-game of loyalty only gains in severity the higher up the scale one climbs, we must struggle to blur the boundaries of where one nation’s, one people’s, or one ideology’s history begins and another one’s ends. Woe to the hapless immigrant who finds him/herself caught between devotion to home and host country, mother tongue and second language, former and future passport.

Booklet for Long Legged Linguistics, solo exhibition at Art Space Pyhagorion, 2013

Booklet for Long Legged Linguistics, solo exhibition at Art Space Pyhagorion, 2013

The proliferation of allegiances – to languages, histories, beliefs – keeps us on our toes, constantly negotiating the pitfalls at the heart of monogamous polemics and brittle identity politics. If we’re steadfast believers in sticking to the singular in our love lives, then surely our affections for places, peoples, histories, languages and countries could and should escape the girdle of the singular and unique and spill joyously into the plural and polyphonic. As our Future City co-panelist Hamid Dabashi put it so eloquently, ‘Every home has its abroad.’

DC: Whether we look to the ancient past or ahead to the future, as Saskia Sassen pointed out, there’s often a sense that cities are a far more robust measure of place and its ideas over the long term than (often recently created) nations. How does your work engage with cities as repositories of interwoven and layered histories? For example, you’ve referenced the importance of Bukhara as an Islamic city, while you’ve also conflated cities with worldviews in Not Moscow Not Mecca …

S&T: Yes, the tenacity of cities as a measure of place, identities, or ideas is a testament to what Antoine Compagnon would call an antimodern tradition (in his Les Antimodernes , astudy of nineteenth-century French literature) and our relationship to time and progress. Like Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’ or Molla Nasreddin himself sitting backwards on his donkey, the antimodern looks to the past but trots into the future, somewhat conflicted about the passing of the pre-modern era. The wild swings between high highs and low lows, despair and elation, suspicion and enthusiasm are very much a feature and engine of urban environments. When viewed from the perch of the early twenty-first century, with the accelerated rise – politically, economically and culturally – of Singapore or Gulf entities such as Qatar, Dubai etc, the examples of Bukhara or other Central Asian khanates or emirates perhaps offer an alternative perspective on the dynamic between cities and nations. The former challenges its historical marginalisation, as the exception and not the rule, to the latter.

Underwater Prayers for Overwater Dreams (the mulberry tree), 2012.

Underwater Prayers for Overwater Dreams (the mulberry tree), 2012.

DC: And finally, when you spend so much time thinking about reanimating the past, telling unofficial, often melancholic stories, with what kind of perspective do you contemplate the future?

S&T: With a particularly Slavic roller-coaster ride of defeatism (appropriately enough, ‘roller-coaster’ in French is translated as montagne russe): we know we’re doomed to fail but we nonetheless try our darndest not to.

1. Slavs and Tatars describe themselves as ‘devoted to an area of the world called Eurasia: between the former Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China’.

2. A Sufi wise man-cum-fool, a well-known folk character throughout Central Asia and the Middle East.

Slavs and Tatars: Founded in 2006, Slavs and Tatars is a collective of artists whose multidisciplinary works function as by-products of connections that they establish between seemingly disparate subjects. They have exhibited widely, with solo shows at Museum of Modern Art, New York (2012), Tate Modern, London (2012), Moravia Gallery, Brno (2012), and forthcoming at GfZK, Leipzig (2014). The collective has published several books that incorporate archival research, texts, original pieces and innovative design. Their work features in collections including the Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE, the Museum of Modern Art New York and the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

Download this article as PDF

Deena Chalabi

Deena Chalabi is a writer and curator. She is currently working as Associate Curator of Public Practice at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. From 2009–12 she was the founding Head of Strategy at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar, where she co-curated the inaugural exhibition of Mathaf’s permanent collection. Chalabi created the Pop-up Mathaf programme for collaborative international partnerships, including the Institute of Contemporary Arts and the Serpentine Gallery in London, and the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. In 2013 she collaborated with the Liverpool Biennial Future City, the Pop-up Mathaf’s most recent programme. She has written for Bidoun, ArtAsiaPacific and The New Inquiry among other publications.

- Future City

Vanessa Boni, Deena Chalabi, Michelle Dezember - Three Scenes and Speculations from a Future City

Rami El Samahy and Adam Himes - Walking Towards Revolution

Omar Kholeif - Interview with Slavs and Tatars

Deena Chalabi - Futurist Library

Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad and Lola Halifa-Legrand - Dispatches on the Future City

Hamid Dabashi - Building a Public Realm: Imagining a Future for Old Doha

Michelle Dezember - What is our Globalised Urban Future?

Saskia Sassen and Irit Rogoff - How do Resources Impact our Ability to Think About the Future?

Noura Al Sayeh - Towards A Thermodynamic Urban Design

Philippe Rahm - What Do We Need to Deconstruct?

Nasser Rabbat - We Are Here to Stay

Jeanne van Heeswijk and Britt Jurgensen - Colophon