Published by

Liverpool Biennial

ISSN: 2399-9675

Editor:

Joasia Krysa

Editorial Assistant:

Hannah Tolmie

James Maxfield

Copyeditor:

Melissa Larner

Web Design:

Mark El-Khatib

Re-figuring Ourselves – A Conversation

Morehshin Allahyari & Christiane Paul

Christiane Paul: Over the past years, your work has consistently engaged with ideas and processes of ‘re-figuring’ – the recreation and reinvention of material forms and bodies. In Material Speculation: ISIS (2015–16) you use 3D modelling and printing to reconstruct twelve statues from the Roman-period city of Hatra, and Assyrian artefacts from Nineveh that were destroyed by ISIS in 2015. Embedded in these recreations are flash drives storing the destroyed artefacts' contexts – images, maps, pdf files and videos gathered in the last months of their existence – making them function as archives that exist outside of institutionalised structures. In SHE WHO SEES THE UNKNOWN (2017–present), you employ 3D scanning and printing to recreate dark goddesses and monstrous female figures of Middle-Eastern origin, using the traditions and myths associated with them to explore colonialism and oppression in contemporary societies from a feminist perspective. What brought you to acts of re-figuring as an artistic practice and to this specific engagement with the materiality of artefacts and figures?

Morehshin Allahyari: A major aspect of my work as an artist and activist in the last decade has been archiving and documentation. Material Speculation: ISIS and SHE WHO SEES THE UNKNOWN are both about archiving, as well as the non-binary connection between history and technology. Re-figuration for me is about activation and preservation. It’s an act of going back and retrieving the forgotten or destroyed histories – from the ones destroyed by ISIS in 2015 to the female/queer figures from ancient Middle-Eastern mythical narratives and texts that are usually misrepresented. Through re-figuration, certain acts of decolonisation can happen. In all these practices, I’ve been interested in alternative, poetic and practical forms of archiving. I think my fascination with archiving or collecting knowledge comes from a love of making marks and leaving traces behind in the context of history and a ‘bigger picture’. For me, it’s important to remember what we live and how we live it and that this time and place we get to be in is a tiny chunk of what then becomes a ‘past’. This thought is what makes archiving a remarkable practice for me: hoping those who come after us will know and remember this past and our stories. For me, re-figuring is going back and re-imaging the past so that we can create and re-imagine alternative futures and worlds; so that we can collapse the political notion of linear space and time as an act of resistance. Re-figuring is a ficto-feminist and activist practice to reflect on the effects of historical and digital colonialism and other forms of oppression and catastrophe.

CP: Your projects use 3D modelling and printing technology, now commonly employed for fabrication in commercial sectors, as a tool for documentation, reconfiguration and resistance. In The 3D Additivist Cookbook (2016), created and edited in collaboration with Daniel Rourke, you compiled a compendium of 3D .obj and .stl files, designs, templates, texts from over 100 artists, activists and theorists as additive/activist ‘recipes’ for living in contradictory times. What attracts you to 3D printing as a tool and how would you describe its potential?

MA: I’ve always thought of the 3D printer as a metaphor and point of departure to delve into and overlap with other disciplines and worlds. In both The 3D Additivist Manifesto (2015) and The 3D Additivist Cookbook we used #Additivism as a network of forces: economic, social, political, material, infrastructural. The 3D printer is a machine that offers the promise of being able – one day – to make copies of itself – a radical metaphor for the capacity of life breathed into the world of inert matter. #Additivism sought to wrest control of 3D printer narratives away from the white tech males who dominate the field. So it’s a call to those on the ‘outside’ to seize control and multiply the possible spaces and worlds they inhabit, from fablabs to commercial spaces. For me, 3D printing is just another technology that has the potential to be used as a tool for resistance and activism.

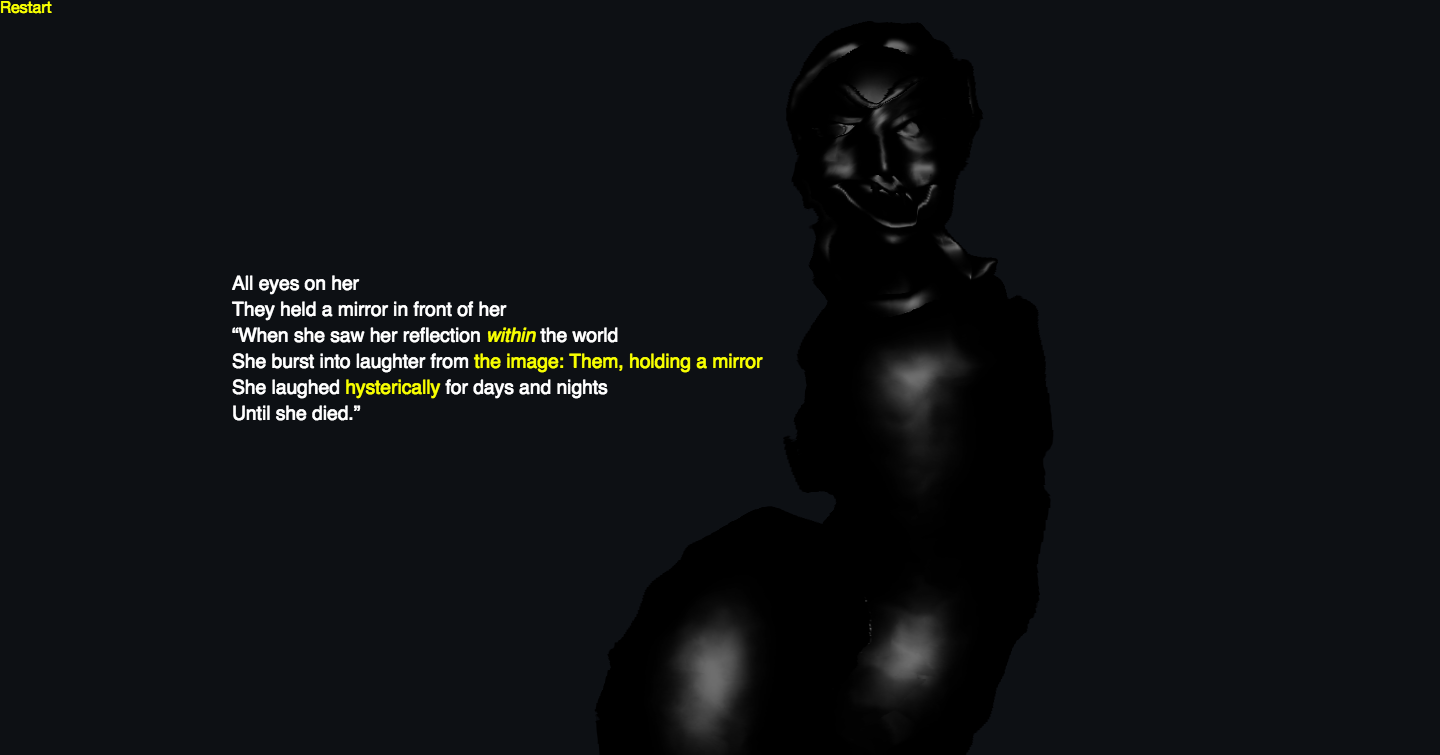

CP: Your hypertext narrative The Laughing Snake (2018) – co-commissioned by Liverpool Biennial, the Whitney Museum of American Art and FACT Liverpool and part of the SHE WHO SEES THE UNKNOWN series – uses a jinn, a supernatural creature or monstrous figure in Arabian mythology, to explore the status of women and the female body in the Middle East. In terms of medium, the work differs from the other pieces in the series in that it takes the form of an interactive online narrative rather than a sculpture and accompanying video narrative. What kind of possibilities did this particular form create for your ongoing exploration of jinn?

MA: I come from a creative-writing background, so in general, fictional writing has always been an important part of thinking and creating for me. In a visual time-based medium like video, the options for a certain kind of storytelling are limited. Once an option like interactivity is available, it expands the possibilities of writing in fascinating ways (another reason why I love the possibilities of technology in relationship/collaboration with more traditional media and forms). For example, I’ve always been really into open-ended writing. And, for me, one of the most exciting aspects of web art and hypertext narrative has been its potential as a format for playing around with this kind of storytelling and narrative-building. The Laughing Snake starts as a non-linear narrative, but as the viewer clicks forward, the narrative gets more and more non-linear and complex. Choice, accident and randomness all become components of experiencing the story through passages that range in tone from poetic to autobiographical. The only way to understand the full narrative, to travel back and forth between past, future and present, is to spend a good amount of time with the piece, which adds mystery and different kinds of relationships to the text, and ways of connecting to other content (sounds, visual, poetics).

CP: According to the original myth appearing in the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Arabic manuscript Kitab al-bulhan (Book of Wonders), the seemingly invincible Laughing Snake had taken over a city, murdering its people and animals, until an old man finally destroyed her by holding up a mirror to her, making her laugh so hard at her own reflection that she died. What drew you to this particular jinn and her story from a feminist perspective?

MA: I came across the story of The Laughing Snake and Mirror in The Book of Felicity and The Book of Wonders. The illustration shows a female snake in a beautiful landscape looking at a group of men who are holding a mirror in front of her. But unlike the myth of Medusa, who turns into stone when she sees herself in the mirror, the Laughing Snake dies from seeing her reflection in the mirror – laughing at it hysterically until she self-destructs. I wanted to turn this story around, to embrace the monstrosity, to change this image and the structure. So in my new story about the Laughing Snake, I chose to show that she isn’t laughing at her own reflection, but rather at her reflection within the world she lives in. Her laughing and her death are powerful gestures to take her reflection back. And I use that to tell real personal stories about the past and present of my life and an imagined future. They’re stories about sexual experiences in Iran, the ownership of a female body in a patriarchal culture and society, and laughter as the rejection of that history, and a way to re-imagine a different kind of world for the women of the Middle East. The power of this work is to remind women, the people of the Middle East, that our figures and our stories, fictional and actual, matter – not just for the present but for claiming an alternative future that isn’t exclusively white or western.

CP: I think your work is very successful in striking a delicate balance: on the one hand, it has its roots in your personal history as a woman being born and raised in Iran and is very specific; on the other, it manages to transcend the personal and resonates on a more general cultural level in its engagement with colonialism, oppression and femininity. How has your unique perspective as an Iranian woman living in the US informed your work process?

MA: I think this is a balance that took a while to build. When I first immigrated to the US from Iran in 2007, a lot of my work was about the experience of censorship in Iran and self-exile as a response to oppression that I experienced growing up. But then, after some years, I wanted to figure out how to connect my life as an immigrant in the US to my background of growing up in Iran, to the world around me as I lived/struggled through it. For me, the answer wasn’t to make work directly about my identity but rather to find elements and stories that were poetic, personal and collective, then find ways to connect them to issues that were of concern to me. So as much as my work comes from a personal place, it also tries to avoid the simple binary representations of who I am (a woman/woman of colour/woman of colour from Iran etc.) and how I am in the world. I decided early on that I wanted my work to go beyond identity politics and I think my love of history and storytelling and my hatred of stereotypical orientalist work really helped me achieve this space in a unique way.

CP: SHE WHO SEES THE UNKNOWN, in particular, falls into the genre of speculative fiction, which has recently gained a lot of traction. Incorporating supernatural, magical or futuristic elements, this form of narrative fiction opens up playgrounds for contemplating scenarios both grounded in and transcending our realities. Your work is a particularly poetic engagement with this form. What led you to explore this poetic-speculative storytelling?

MA: Science fiction is a genre that doesn’t really exist in Iran. We have a lot of mythical stories and tales in our literature, a lot of poetry and imaginary thinking about the past, but almost no imaginary thinking about the future. I don’t think I even realised this until 2012, when I started to work on Dark Matter (2014) and the #Additivism project and fell in love with futuristic-thinking, speculative fiction and content such as Afrofuturism, Ethnofuturism etc. So the almost nonexistence of this kind of language and imagination in Iran/the Middle-East made me really curious and tempted me to make work that could build a platform for this. We (as Middle-Easterners) have to be able to imagine/re-imagine ourselves in the future – a future that’s mostly built for the Western white demographics with no/very little room for us. And when I talk about the future, I don’t necessarily mean the far future. I mean tomorrow, a month from now, next year. That kind of understanding of time and space-building is extremely important to me and the kind of speculation/imagination I want to create with and for it.

CP: Related to time and space-building in your work is the endeavour to repair history and memory, which seems to have enormous cultural urgency. We’re living in a time when concepts of fact and truth have become contested territory and history is frequently rewritten for political purposes. What does the process of mending history and memory entail and why is it important to you?

MA: Growing up in Iran, I remember I was constantly reminded that there are many versions of the truth and history. One version is that told by the government and fed to us in schools, media and public spaces; another is that told by my non-religious parents; yet another is told by the Western media ... and the list goes on. From a very early age I learned that I have to search for reliable information, and when studying media and social sciences for my degree in Iran, I learned a lot about propaganda and agenda-setting as it relates to news and facts; how there’s no such thing as passive technology and ‘one truth’. So art (and to be more clear, art-activism) became a fascinating way for me to play with these power structures and to find a voice for resistance. Archiving became a position and practice that I took very seriously as part of this process. And so, for example, the re-creation of the destroyed artefacts by ISIS and the re-figuration of the female/queer monstrous figures of the Middle East in She Who Sees The Unknown became a methodology for challenging the limitations and possibilities of remembering and forgetting.

Morehshin Allahyari, SHE WHO SEES THE UNKNOWN: The Laughing Snake, 2018. Hypertext narrative. Commissioned by Whitney Museum of American Art, Liverpool Biennial and FACT. Images courtesy the artist

Download this article as PDF

Morehshin Allahyari & Christiane Paul

Morehshin Allahyari lives and works in New York, USA. Allahyari is an artist, activist, and educator. Her work deals with the political, social and cultural contradictions we face every day. She thinks about technology both as a philosophical tool to reflect on objects and as a poetic means to document our personal and collective life struggles in the 21st century. Her modelled, 3D-printed sculptural reconstructions of ancient artefacts destroyed by ISIS, titled Material Speculation: ISIS, have received widespread curatorial and press attention and have been exhibited worldwide.

Christiane Paul is a curator, professor and writer who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She is Chief Curator/Director of the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, Professor of Media Studiesat The New School and Adjunct Curator of Digital Art at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She is the recipient of the Thoma Foundation's 2016 Arts Writing Award in Digital Art, and her recent books are A Companion to Digital Art (Blackwell-Wiley, 2016); DigitalArt (Thames & Hudson, 3rd edition 2015); and Context Providers – Conditions of Meaning in Media Arts (Intellect, 2011). At the Whitney Museum she curated exhibitions including Programmed (2018), Cory Arcangel: Pro Tools(2011) and Profiling (2007), and is responsible for artport, the museum’s portal to Internet art. Other curatorial work includes Little Sister (is watching you, too) (Pratt Manhattan Gallery, NYC, 2015) and What Lies Beneath(Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul, 2015).

- Introduction: Beautiful world, where are you?

Joasia Krysa - Beauty: A Logistical Imaginary [1]

Jussi Parikka - Excerpt from ‘Climate Grief and the Visible Horizon’

Meehan Crist - Outlawed Social Life

Candice Hopkins - Re-figuring Ourselves – A Conversation

Morehshin Allahyari & Christiane Paul - Forensic Aesthetics

Eyal Weizman - Technology, magic and the quest for meaning

Ryan Avent - Self-repairing Cities

Mark Miodownik - Alien Speak: Linguist Dr Jessica Coon on Villeneuve’s ARRIVAL

Jessica Coon - Outside the Hit Factory: The Playlist

Alexander Provan - Colophon