Published by

Liverpool Biennial

ISSN: 2399-9675

Editor:

Joasia Krysa

Editorial Assistant:

Hannah Tolmie

James Maxfield

Copyeditor:

Melissa Larner

Web Design:

Mark El-Khatib

Excerpt from ‘Climate Grief and the Visible Horizon’

Meehan Crist

The talk today is titled ‘Climate Grief and the Visible Horizon’, and I thought we might start with a story from Ovid. This is the story of Phaethon and Phoebus. The second book in Ovid’s Metamorphoses opens with this story, which is the longest in the book. Phaethon is the son of Phoebus, who is the Sun god, and is also the son of a mortal woman. He’s living on earth with his mortal mother and feeling as if he’s not being recognised by the god as his rightful son. Phaethon goes up into the sky to visit Phoebus and asks him to bestow some kind of sign that he is indeed his father. Phaethon wants to prove to everyone back down on earth that he is the person he says he is. So, Phoebus says, ‘Ask me whatever favour you want, and I’ll bestow it.’ The boy says, ‘I want to drive the chariot.’

The chariot crosses the sky every day, drawn by magnificent horses, taking the sun through the day. In order to do this, it has to pass through the zodiac along the way. Phoebus says, ‘Please ask me for anything else. Don’t ask me for something that can only end in your demise. You’re too young, not strong enough. Even the other gods cannot control this chariot.’ But the boy is headstrong and bent on driving the chariot, and finally his father relents and gives him the reins and off he goes into the sky. The horses take one look at the terrifying things up there in the celestial firmament and they bolt. The kid can’t control them; he goes way out into the darkest outer reaches of space, and comes back down, far too close to Earth, and the flaming ball of the sun begins scorching the Earth. There are these really beautiful passages – this is from the translation by David Raeburn:

The earth now burst into flames on all of the hills and the

mountains,

split into huge wide cracks, and dried as it lost its moisture.

The corn turned white and the trees were charred into

leafless skeletons;

Parched grain offered the perfect fuel for self-ruination.

These losses were trifling. Destruction fell upon great

walled cities;

mighty nations with all their peoples the conflagration

turned into ashes…

Phaëthon now looked down on a world in flames …

Wrapped in the pitchy darkness, he didn’t know where he was going.

So, there’s this moment when he hung in the sky with these horses running wild, and he looked down and saw everything on fire. Then there’s a very moving part of the story where the Earth, scorched and parched-lipped, calls out to Jupiter, saying, ‘You have to do something. I’m dying.’ The earth beseeches the ‘king of the gods’:

Look round at the two poles:

Smoke is pouring from each. If they suffer from

fire,

the halls of the gods will collapse. See, Atlas himself is in

trouble:

his shoulders can barely sustain the weight of the white-hot

vault.

I beg you to rescue what is left from the flames. Take thought for the good

of the universe!

Jupiter hears this plea and fires a thunderbolt at the boy and the chariot. Phaethon is instantly killed, and his corpse comes raining down from the heavens, with his hair on fire like a comet, and the horses go plunging into the ocean.

Johann Liss, The Fall of Phaeton, early seventeenth century. Collection of the National Gallery. Sourced from The Yorck Project

Phaethon’s father is stricken with despair and doesn’t want to ride the chariot anymore, but the other gods get together and say, ‘You have to. You’re the only one that can do this. We need the day. You must take the chariot across the sky’, and he agrees to drive it again.

I’m drawn to this story, because there’s a very obvious way to read this as a metaphor for climate change. These days, it seems a little bit too on-the-nose. I don’t know if you saw on the news this week: the Arctic Circle is on fire, as happens in the story. Japan had its hottest temperature in recorded history: 106 degrees Fahrenheit. Anyone who has been following climate change news, or just the news, knows that things are dire. To go back to the story of Phoebus and Phaethon, there’s a way to read this, where humanity is the boy: human hubris and a desire to take control of a thing that was never meant to be ours and running the world into destruction. Ted Hughes wrote a poem based on this story as a climate-change metaphor. But I think we can read it a little differently. I’m interested in shifting the identification from the boy to the people on Earth, because, much like climate change now, the ‘on-the-noseness’ of this story involves marginalised people who aren’t the ones responsible for the destruction they’re seeing and living through, and they remain basically voiceless in this poem. What if we, as readers, shift our identification to the people on Earth and start imagining the people in those cities and fields that are burning to the ground, where the rivers are drying up – what does it feel like to witness that kind of destruction? What kind of horror and what kind of grief do they feel? I’m particularly interested in this question of grief, in part because we’re all feeling it in different ways.

Is anyone in here familiar with the Jet Stream? Is anyone worried about the dawn of a new Ice Age in Europe? Because that could happen. It could happen sooner and faster than previously thought.

Collectively and individually we’re experiencing what no generation of humans has ever faced, which is grieving the on-going loss of the planet as we’ve known it. This can mean loss of homes to fire and flood, but it can also mean things like loss of your favourite childhood beach, a place with which you identify, that feels like home and part of who you are that’s now gone and you can never go back to. It also means loss of jobs, income and food security. When fisheries collapse because there are no fish in the sea, you’re losing whole towns, cities, industries, cultures that are based on these fish existing. We don’t really have good language for talking about this kind of grief and we don’t really know what it looks like yet – the contours are still blurry. We don’t know how to think about and therefore process this grief in a way that might enable us to move forward.

Alexey Savrasov, Landscape with a Rainbow, 1881. Collection of the Latvian National Museum of Art

I thought I’d look at a few of the grief paradigms we do have to see how they can help us to understand this particular moment. Freud’s On Murder, Mourning and Melancholia includes a classic essay in which he defines the difference between mourning and melancholia. Mourning is a totally normal human reaction to loss, ‘the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one's country, liberty, an ideal, and so on’. So, it’s the loss of something meaningful, and mourning that loss is a normal process.

Sigmund Freud, On Murder, Mourning and Melancholia, Penguin Classics, 2005

Melancholia is different. It includes a prolonged period of mourning, and all the same features, but with a pathological skewing of self-regard – you basically start to hate yourself a little bit. Freud writes, ‘Profound mourning, the reaction to the loss of someone who is loved, contains the same painful frame of mind, the same loss of interest in the outside world – in so far as it does not recall him – the same loss of capacity to adopt any new object of love (which would mean replacing him).’ This is really interesting, this idea that you’re hanging on to the thing or person that was lost because if you let them go to love something else, it’s like a rejection of that previously loved thing. Then there’s what Freud calls ‘a disturbance of self-regard’. So, other than the disturbance of self-regard, mourning and melancholia are very similar processes, but melancholia just won’t end. You stay transfixed and frozen in melancholia, unable to move forward.

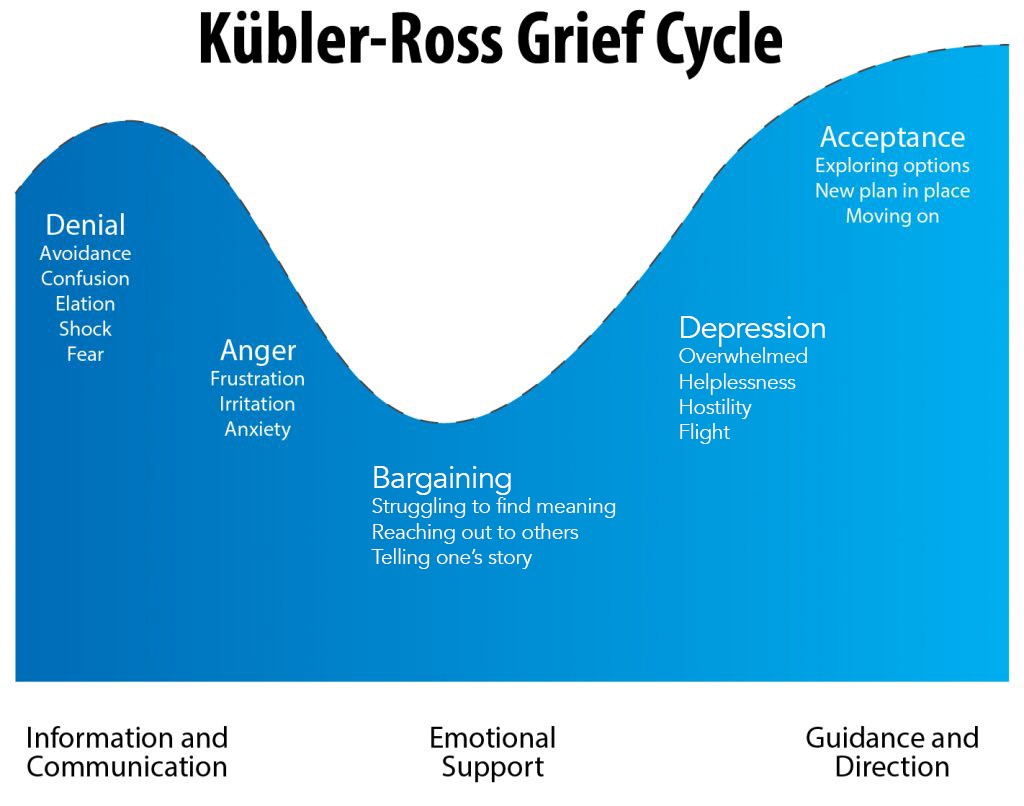

Elizabeth Kubler Ross and David Kessler, Five Stages of Grief, 2005. Image sourced from psychom.net

Moving a little later in time, we have the classic Elisabeth Kübler-Ross ‘five stages of grief’: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I rather like this image because the ‘acceptance’ hill is higher than the first hill, so there’s some implication here that you’ve actually moved up and forward and ended up somewhere better than you were before. This paradigm roughly aligns with Freud’s idea of mourning, but breaks it into stages.

There’s another paradigm that came up in the 1990s: ‘complicated grief’. This describes prolonged grief associated with a death, more like melancholia. If Kübler-Ross’s model is similar to mourning, this is more like melancholia. The symptoms of complicated grief are the same as those of normal grief, but the defining element is the duration of the feelings. You get stuck in this form of very acute grief where the future seems bleak and empty. That idea, and the feature of pathological mourning, seems useful for us when thinking about climate change. Complicated grief is one where the griever ‘experiences their negative symptoms as a way of remaining connected to the lost loved one’. Again, there’s an echo of Freud: that grief is a form of love; if you stop grieving, you’ve stopped loving and that in itself is painful.

According to Dr Katherine Shear at Columbia University, complicated grief occurs in only a small percentage of people. For people who suffer complicated grief, their other relationships tend to be very difficult. The diagnosis is most often reserved for those who have a family or personal history of mental-health disorders. Grief can be complicated for many reasons, but fundamentally the griever has an inability to process the grief, to emotionally handle it in the more ‘normal’ sense of mourning.

Both the Kübler-Ross paradigm and this complicated grief paradigm stress finality. Someone has died. Something is gone and there’s been a very concrete loss. It’s the job of the mourner to grieve appropriately and move on. This doesn’t really map on to climate change, because we don’t know what the loss is – or will be. If you look at sea-level rise (if we go back to our map over here) we don’t know if the flooded areas here represent a worst-case scenario, and it’s not clear that this map shows the end point. Flooding might end somewhere sooner than this, or in 200 years it may have moved much further inland than this. So we don’t have that finality with which to grapple and which can actually help us decide how to move forward.

‘Ambiguous loss’, I think, is a more useful grief paradigm for us. This was a psychological paradigm established in the 1970s by Pauline Boss, who was studying and working with people whose family members had gone missing in action. In classic grief paradigms, the object of attachment has gone and has to be mourned, but with ambiguous loss, the object of love is physically absent, but without a sense of finality – as such, it remains psychologically present. It seems as if it, or they, might be able to come back. A friend of mine recently told me a story about a friend of her mother’s who had a son who went missing in action, and twenty years later someone in uniform was walking up to the house and she went racing out of the front door thinking it might be him. There’s no end to the possibility that the object of love might return, which is one type of ambiguous loss.

Pauline Boss, Ambiguous Loss: Learning to live with Unresolved Grief, 2000, Harvard University Press

The other type of ambiguous loss is where the object of your love is still physically present but psychologically absent. For example, someone with Alzheimer’s. The person is still there; you can still sit by them and hold their hand. You can still feel love for them and be in the same room with them, but at the same time, they’re not there. And they’re not there in a complicated, shifting, sliding way where you’re never sure how much they are or are not there at any given moment. How do you grieve the loss of someone who’s sitting right in front of you?

Even ambiguous loss doesn’t map perfectly to the loss felt as a result of climate change, because the end point is still known. With the Alzheimer’s patient, you know that they’re going to die – at the end of that process, there’s going to be a finality. With ambiguous loss, and this is a quote from Boss, ‘There is no closure. The challenge is to learn to live with the ambiguity.’

When it comes to climate change, we don’t have a paradigm for grief that requires us to embrace both ambiguity and finality. We don’t have a paradigm for grief that is both personal and global. That is, both your home and the Arctic are on fire. Climate change presents us with a lot of kinds of grieving to try to put into one coherent psychological space, both as individuals and as a collective humanity, such that we might be able to move forward. And so, we’re stuck in this gap, which feels like chaos but also makes some sense, psychologically. The question becomes, how do we decide what to let go of, what to mourn, so that we can move forwards?

Download this article as PDF

Meehan Crist

Meehan Crist is writer-in-residence in Biological Sciences at Columbia University, and was previously editor-at-large of Nautilus and reviews editor of The Believer. Her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The New Republic, The London Review of Books, Tin House, Nautilus, Scientific American and Science. She is the host of Convergence, a New York-based live show (and soon-to-be podcast) about the future, which invites speakers from different fields to explore how emerging science and technology will affect culture, society and politics. She is also co-editor of the forthcoming nonfiction anthology What Future (Unnamed Press, 2018).

- Introduction: Beautiful world, where are you?

Joasia Krysa - Beauty: A Logistical Imaginary [1]

Jussi Parikka - Excerpt from ‘Climate Grief and the Visible Horizon’

Meehan Crist - Outlawed Social Life

Candice Hopkins - Re-figuring Ourselves – A Conversation

Morehshin Allahyari & Christiane Paul - Forensic Aesthetics

Eyal Weizman - Technology, magic and the quest for meaning

Ryan Avent - Self-repairing Cities

Mark Miodownik - Alien Speak: Linguist Dr Jessica Coon on Villeneuve’s ARRIVAL

Jessica Coon - Outside the Hit Factory: The Playlist

Alexander Provan - Colophon