Envisioning Public Cooperative Housing

Gabriela Rendon

Envisioning new housing paradigms amidst the current housing crisis may be overwhelming and sometimes disempowering for communities in large urban areas dominated by profit-driven development, as is the case with New York City. Nevertheless, there are few places with such powerful tools and assets as those owned by New Yorkers. They have one of the most valuable housing legacies of the country, have lived in collectivity for centuries, reformed housing legislation, regulated a third of the city’s rental housing, and occupied and reinvented the neglected city for the common good. Unfortunately, greater forces have taken over New York, burdening progressive actions. To reclaim the city it is necessary to learn from successful experiences leading to housing justice and co-producing innovative processes achieving new housing paradigms. There is no perfect formula to embark on such an ambitious task, but the following actions can be adopted not only in this thrilling urban area but also in other cities facing the same problems and having similar capacities:

(1) Co-produce knowledge about the agents of housing inaccessibility, as well as around local needs, priorities and assets through participatory action research or any other method combining scientific and popular knowledge.

(2) Learn from progressive housing antecedents that have preserved affordable housing and kept communities together by scrutinising successful local housing and development approaches as case studies, as well as public programmes and instruments that have supported them, while concurrently interrogating the stimulating effect that state-sponsored housing programmes can exert on the creative and latent productive capacity of the under-housed, the displaced and those at risk of homelessness.

(3) Identify current federal, state and local policy determinants and finance mechanisms assisting in neighbourhood and community stabilisation in order to complement, integrate and implement potential new housing models.

(4) Envision a hybrid tenure framework for the provision of permanent affordable housing, always taking into account the previous enquiries.

(5) Formulate actionable strategies to implement a pilot project and eventually expand the housing model.

1. The problem to fight against

Alternative housing models to homeownership, such as rental housing, cooperative and collective housing have become scarce in America while owner-occupied housing rates keep growing. Homeownership has been seen as the hegemonic tenure system, placed at the centre of housing policies and facilitated through the provision of housing finance. Most housing policies have targeted individuals to promote homeownership – in many cases even the less well-off – assuming that everyone has the resources to access adequate and affordable housing. However, this is not always the case.

Firstly, the financialisation of housing, which is the promotion of access to housing through housing finance, has led to an unprecedented urban crisis affecting low, and moderate-income families. As a result, housing has become a commodity for household wealth accumulation and has been accessible to only a few. Meanwhile, market-based housing development and financing has fuelled an incremental rise in prices at the expense of housing affordability. It’s clear that this model assists only financial institutions – not people. Since 2008, millions of Americans have lost their properties due to foreclosures, many of them ending up on the streets.

Secondly, the share of public housing has decreased significantly since public funds have focused mostly on programmes, grants and tax abatements to stimulate homeownership and profit-driven development rather than focusing on the new construction of public housing or alternative housing programmes for the most vulnerable populations. In addition, much of the subsidised and public housing stock has been increasingly privatized. Thus besides the decrease in affordable housing, the provision of public housing has also declined.

Thirdly, the provision of affordable housing has been promoted through the provision of tax abatements and bonus floor-area ratios to new market-rate housing developments, which in exchange should contribute with a small share of housing for low-income households. Unfortunately, most of these incentives have assisted mostly developers and the better off. In many cases, the surrounding community cannot afford to live in the ‘affordable’ units, which eventually become market rate.

Fourthly, and most seriously, many who formerly had access to housing have been struggling with displacement and homelessness in recent years. This has been reflected in the number of homeless in the shelter system, which increased from 37,390 in 2000 to over 54,600 in 2014. Perhaps the most striking statistic is the number of families with children. The New York City shelter system currently houses over 11,000 families and over 23,500 children (NYCDHS 2003, 2014). Children make up almost half of the shelter population. These numbers exclude the street-dwelling homeless people, hundreds of families waiting for a shelter place, and the thousands of households living in overcrowded conditions throughout the city due to the lack of affordable housing.

Finally, parallel to the previous conditions, the number of vacant properties has remained steady due to misguided urban policy, urban decline, speculation and foreclosures. Low-income districts hold significant amounts of vacant lots and buildings all over New York City. This aspect can be identified as a problem, but also as an asset. It is presumed that if the under-utilised, derelict and vacant buildings in the city were rehabilitated and made accessible to the thousands of people struggling for a place to live, the housing crisis would be resolved.

These are general aspects that everyone can grasp. Nevertheless, it is necessary to dissect the agents affecting each community district and their specific needs, priorities and assets in order to achieve transformative changes. Participatory action research can be used as a tool of enquiry. It is an effective and powerful approach to economic, social and political change, since it actively engages people in generating knowledge about their own living conditions in order to produce fundamental reorganisation of urban social, economic and spatial systems and relations of power.

In general terms, the main housing needs and priorities for the great majority of New Yorkers are as follows: spending no more than 30% of monthly income on housing; holding a right of continued occupancy; living in decent and safe dwellings; and having a stake in decisions over one’s living environment. Nevertheless, most New Yorkers struggle to achieve even one of these priorities. This fact has provoked large-scale mobilisations among citizens, academics, activists, grassroots groups and community-based organisations. Knowledge, resources and other assets have been shared. Local coalitions have worked diligently with local authorities, drafting legislation to facilitate access to vacant properties, promoting the creation of Community Land Trusts, and envisioning development avenues to create affordable and community-controlled housing. Their achievements are admirable and of great value for communities, but there is still so much work to do and significant limitations for low-income communities. First of all, accessing land in the ‘real-estate capital’ of the world is near to impossible. Secondly, expertise on housing planning, design, development and management is limited. Thirdly, fragmentation and competition among community groups advocating for affordable housing is common. Fourthly, public funds, loans and tax abatements usually assist well-established community-based organisations or housing corporations, which often look after their own needs and priorities rather than those of the community. Lastly, communication and cooperation between city authorities and communities has been nearly eradicated. For instance, community and tenant-led initiatives and other sorts of sweat-equity public programmes have decreased or disappeared, leaving housing development and rehabilitation only to developers and outgrown non-profit housing corporations.

2. The models that have successfully housed low-income communities in perpetuity

Despite the rich history of housing in New York City, local authorities have opted to forget such an invaluable legacy. Housing policy and programmes based on the welfare of people – favouring workers and those who make the city – have been replaced by housing approaches for profit – aiding the real-estate sector and those who capitalise on the city. It is critical to re-examine such a legacy in order to envision new housing paradigms. Community and tenant-led housing programmes for the rehabilitation of in rem (foreclosed by the city)occupied and vacant city-owned properties, and other types of self-management practices that took place during the 1970s and 1980s, are worth scrutinising. The Sweat Equity, Urban Homesteading, Community Management and Tenant Interim Lease programmes emerged in response to the striking landscape of vacant buildings throughout the city and initiatives led by low-income groups to take over and rehabilitate those spaces through organised efforts. These grassroots practices evolved into local and federal community and tenant-led programmes addressing not only the thousands of neglected buildings but also the deficit of public-housing provision and the ongoing decline of inner-city neighbourhoods and communities of colour. Sweat equity and mutual aid were at the centre of their approaches. These programs have been key for community and tenant control over land. Most of the buildings rehabilitated during this period were transferred to tenants, community management organisations or became limited-equity housing cooperatives, which are now important assets for low-income groups.

Housing cooperatives are not-for-profit membership-based cooperative corporations in which members do not receive a deed to the unit but become shareholders. Each shareholder is granted the right to occupy a housing unit by paying a monthly amount to cover their share and the operating expenses, including mortgage payments, property tax, management, maintenance, insurance, utilities and contributions to reserve funds. Cooperatives can create their own bylaws to impose restrictions on shareholders as long as the board does not violate federal and state housing or civil-rights laws. Some of the benefits include personal tax deductions, lower turnover rates, lower real-estate tax assessments, controlled maintenance costs and resident participation and control in decision-making. In other non-profit housing corporations, decision-making is vested with the non-profit’s central authority, and residents usually act as advisors. Housing cooperatives fall into a number of categories, including equity, non-equity, limited-equity and leasing cooperatives.

(1) In equity housing cooperatives members own a share of the housing cooperative corporation, which owns the land, the buildings and community facilities. Members have control of decisions through a board of directors and they are able to sell their shares at a market price.

(2) In limited-equity cooperatives members also own shares, manage and control the cooperative but cannot sell shares at full market price. This cooperative model builds limited equity for shareholders with restrictions on what outgoing members can gain from their shares.

(3) In non-equity housing cooperatives members usually manage and control the cooperative but instead of owning a share they have a long-term lease that is granted by the cooperative housing corporation. The price of the units is regulated by the board. Financing is carried by the cooperative corporation. Usually these cooperatives get substantial public funds.

(4) A leasing cooperative leases the property from an outside entity, privately or publicly owned. Cooperative members also participate substantially in management and control. Usually the lease is long-term and sometimes with an option to buy. Members may enjoy similar benefits to other types of cooperatives holding title, but usually do not accumulate equity. The leasing approach can make available properties to low-income cooperatives.

Housing cooperatives are still a popular housing model in New York City. They house from high- to very low-income households. Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFCs) , are a special type of limited equity cooperative in New York City. These former city owned properties were sold directly to tenants or community groups through some of the public programmes mentioned above to provide low-income housing. There are about 1,700 HDFC buildings, with more than 30,000 units of affordable housing today. Other housing cooperatives are run by non-for-profit corporations or by Mutual Housing Associations, which are non-profit corporations set up to preserve and develop cooperatively owned and non-profit tenant-controlled properties. Mutual Housing Associations have helped in the prevention and elimination of neighbourhood deterioration and the preservation of neighbourhood stability by affording community and resident involvement in the provision of high-quality, long-term housing for low- and moderate-income families in which residents participate in the housing management, have the right to continued residency, and have an ownership interest in the occupancy agreement conditional upon compliance with its terms, but do not possess an equity.

On the other hand there is public housing,which is rental-housing owned and managed by the central or local government, aiming to provide permanent affordable housing. The New York City Housing Authority is the most successful public-housing programme in America and probably the one for which there is still the most demand today, despite its lack of popularity among New Yorkers due to inadequate maintenance and stigmatisation. This public programme houses over 500,000 residents, about 5% of the city population – the very low-income – with a waiting list of nearly a quarter of a million (227,000 in 2013).

Another housing model taking place, mostly informally, all over the city is co-housing . Nearly 5% of renter households live in severe overcrowding, where households comprising persons who are not necessarily related share facilities and services. In general terms, co-housing developments are usually designed, developed and managed by residents, which use consensus as the basis for group decision-making. Households own their units and share community facilities such as kitchens, working spaces, gardens,visiting and play rooms. Co-housing can be developed on different scales: building, block, neighbourhood etc. Co-housing developments may have one of the three following legal forms of ownership: individual (private) with common areas owned by a homeowner association, condominiums, or cooperative housing corporations.

Last but not least, Community Land Trusts(CLTs) have been considered one of the most powerful and efficient tools currently available to communities to provide and preserve low-income housing in perpetuity while buffering the community from both aggressive land speculation and the dislocating effects of gentrification. The CLT is a local non-profit organisation created to acquire land on behalf of the community and to hold it in trust. The CLT provides 99-year renewable leases for exclusive use in accordance with the terms of the trust. The lessee is typically a non-profit housing corporation, mutual housing association, or limited-equity cooperative that rents to qualified tenants, or an individual owner whose ability to profit from equity gains is extremely limited. A key feature of a CLT, and an important distinction between CLTs and traditional Community Development Corporations is the composition of the Board of Directors. The board is composed of three different groups, each with equal representation intended to balance the interests of the community stakeholders – residents (tenants or homeowners), community leaders and housing advocates (not CLT leaseholders), and public representatives (local government and other local not-for-profit organisations).

Some of the multiple benefits of CLTs are:

(1) Preserving and protecting public investment allowing one subsidy to keep operating for a century or longer rather than the average twenty-year span of most public subsidies.

(2) Strengthening the local community through the interdependency of CLT partners.

(3) Providing flexibility to respond to different housing types such as cooperative housing, rental housing, owner-occupied housing, senior and mixed-use housing.

(4) Keeping assets in the community by facilitating the transfer of private and public ownership to community ownership.

(5) Facilitating the acquisition and management of land for non-housing community needs (industry, business, community facilities, green space, etc).

In addition to this classic model, there are alternative ways to create a CLT: as a CLT programme of existing organisations; as a CLT corporation established by existing non-profit organisations; and as a CLT corporation established by government.1 According to the CLT network:

it has become increasingly common for local governments to take the lead in establishing CLT…Some government officials believe that if government is going to put public resources into a CLT program it should control the program to ensure that the resources are used responsibly and effectively. In other cases, local governments…have wanted the CLT to be a fully independent organization. In their view, an independent nonprofit organization –more or less insulated from political motivation and buffered against the potentially destabilizing effects of electoral politics –is better positioned to carry out a CLT program consistently over an extended period of time, at least if there is reason to think that it can maintain a strong working relationship with its local government.2

3. The instruments leading to expandable models of permanent affordable housing: maximizing state and community benefits

The Inclusionary Housing Program has been a local instrument providing affordable housing in areas of the city undergoing substantial re-zoning and development by offering a bonus floor area to developers in exchange for the creation or preservation of housing for low- and moderate-income households, on-site or off-site. Another instrument has been the 421-a Program, which provides tax abatements for a specific period of time (usually twenty years) to projects in exchange for a percentage of affordable housing. Both programmes were originally created for high-density districts, especially in Manhattan, and later expanded to medium- and low-density districts in the boroughs, usually low-income areas. Unfortunately, in the lifetime of the programmes, only a small percentage of the housing units, for rental and ownership, have been affordable for communities living in those areas, and the few opportunities do not guarantee permanent affordability. Affordable units are usually registered in the rent-stabilisation programme for the first years and eventually become destabilised. There are no effective legal instruments to keep affordable homeownership opportunities. Most of the benefits have been for developers and better-off households. In fact, some developments have benefited from both programmes, profiting from a number of public funds, tax abatements and subsidies.

One of the avenues for the provision of permanent affordable housingis to enforce those who benefit from these programmes to donate a percentage of the land (in the case of large re-zoning developments) or a fee equivalent to the cost of the 20% of the total housing units that is now required to be set aside exclusively for low-income households. This fee would go into a City Affordable Housing Fund (CAHF)to be used for the implementation of a new public programme that will guarantee permanent affordability while maximising public and community benefits.

Other potential instruments would be taxing at a higher rate vacant land that is underdeveloped due to speculation, as well as creating a non-profit land bank to acquire under-utilised, contaminated or vacant properties and transferring those properties to CLTs. These instruments have been pushed at city and state level in recent years. The collected land and funds could contribute to the creation of a new housing initiative.

These and other public funds available for the provision of affordable housing –pension funds, tax credits, etc– can be evenly distributed for the construction of housing to accommodate all New Yorkers. The issue is that those funds are currently directed to a large share of moderate- and middle-income housing development and a small share of very low and low-income housing.

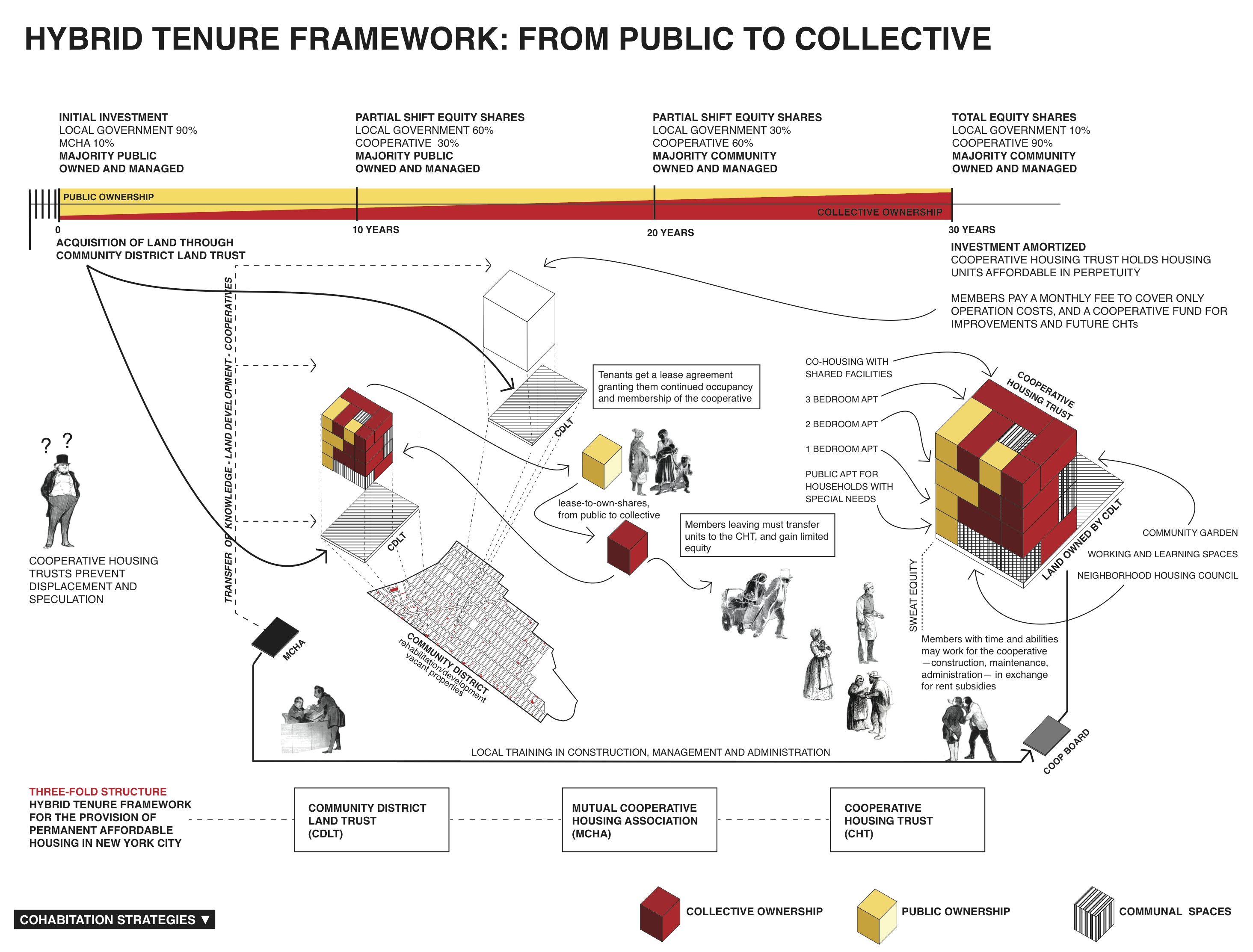

4. Hybrid tenure framework for the provision of permanent affordable housing in New York City3

The proposed initiative aims to provide permanent affordable housing for very low, low and moderate-income households through the development of a hybrid tenure framework. Unlike currently available affordable-housing options, this model is not fully owned and managed by a public or a non-profit entity, nor by a cooperative housing corporation. This housing model is planned, financed, developed, managed and owned collectively by all of these entities alongside community stakeholders and residents. The co-ownership is one of its key features. Since housing cooperatives –particularly limited and non-equity cooperatives– face financial difficulties when constructing and expanding new housing, this model proposes the development of cooperative housing sponsored by the public sector and co-managed by public representatives, community and cooperative members. Public shares may start as high as 90% and decrease over a period of thirty years to 10%. The share granting ownership, management and control over the cooperative reverts from public to collective (through a trust) once the development is fully paid and cooperative members have built the required skills to operate the maintenance and financing of the property.

This housing model combines some of the organizational and legal frameworks of cooperative-housing corporations, mutual-housing associations, community-land trusts and co-housing developments, as well as some of the instruments of the tenant and community-led housing programmes that have created and preserved communities in NYC. Theproposed hybrid tenure model is comprised of a three-fold structure: a Community District Land Trust, a Mutual Cooperative Housing Association, and one or more Cooperative Housing Trusts.

Community District Land Trust (CDLT)

The aim of the proposed CDLT is to acquire properties located in a circumscribed area (community district, as it is currently rendered in NYC) and hold them in trust for the development of Cooperative Housing Trusts. The CDLT is envisioned as an independent non-profit publicly sponsored and managed by a board with equal representation from public authorities(eg. municipality, local city-council office, community board, etc); non-resident community stakeholders; and Cooperative Housing Trusts’residents.

Community Land Trusts have been coveted in the last decades by community-based organisations, housing advocates and activists in order to preserve and develop permanent affordable housing. However, and despite the efforts, communities have faced all sort of difficulties in acquiring properties in large urban centres. Real-estate values are high and expertise in financing and management is not always sufficient among community members. Thus, in order to facilitate the acquisition of properties, members of the proposed CDLT—a cohort of people with diversified expertise and resources— look for abandoned or neglected properties, as well as those holding tax arrears, legal or environmental problems, and reach out to landowners to negotiate possible avenues to acquire the properties. Eventually the city acquires the properties and transfers them to the CDLTfor the development of permanent affordable housing. The transfer of the properties could be also accomplished through non profit land banks, public concessions or donations from re-zoning processes.

Mutual Cooperative Housing Association (MCHA)

The proposed MCHA is a district-based non-profit organisation set to develop, finance, and operate Cooperative Housing Trusts for an interim period. In order to sustain cooperatives over time, it creates local expertise to manage and preserve the affordability of the cooperatives. MHCA’s role is to draft a district-housing plan according to local needs and priorities: to rehabilitate buildings or develop new land provided by the CDLT; to pull together an organisational structure comprised of experts outside and within the community; to develop and operate the cooperatives; and to train locals in construction, maintenance and management skills to run the properties, so that when ownership passes to the cooperative, members can take control and make their own decisions.

Credit: Cohabitation Strategies

The majority of the capital cost of each Cooperative Housing Trust, about 90%, is sponsored by the local government, while the planning and management cost, about 10%, is provided by the MCHA. This fee guarantees the cost of the first development phase: research and planning. The seed money (10%) could be granted by a private foundation; financed by a private entity with a low rate interest; collected through crowd funding (community members) or other private and public contributions, which can be raised prior to initiation of construction. The public investment of the development is projected to be fully amortised in thirty years. During this period, the city gradually transfers its shares to the cooperative while keeping only 10% in perpetuity. During the first thirty years, cooperative members pay a monthly fee to cover the financing, operational costs (maintenance, real-estate taxes, etc) and to contribute to a cooperativefund. Once the development is fully amortised, the cost of the monthly fee drops to cover operation expenses and to finance future cooperatives. These cooperatives encourage collective control among those with lower incomes while providing long-term reliability in meeting the supply of permanent affordable housing and in maximising the benefits of public funds. These cooperatives are structured with equity limitations, imposing restrictions against speculation or rent increases by requiring that members leaving the cooperative transfer the units back to the cooperative.

Cooperative Housing Trusts– public ownership shifting to collective over time

The Cooperative Housing Trusts have been envisioned for the rehabilitation, repurposing and construction of abandoned, vacant and underutilized properties —residential buildings, industrial sites and lots. Their purpose is providing and preserving permanent affordable housing through shared management and ownership. The hybrid tenure of these cooperatives does not only mean the combination of public and collective ownership; this model offers different housing types and sizes for singles, couples, small and large families, as well as particular and co-housing accommodations. Co-housing units offer affordable housing opportunities to large families or households with special needs, such as single parents or seniors, who often require mutual aid and companionship. This option includes private rooms and shared facilities, such as kitchens, bathrooms, play-rooms, living and working spaces. The units target households (of one, two, three, four or more dwellers) with different incomes, from 40 to 90% of the Area Median Income. Last but not least, tenure may be short or long term. A number of units are set aside to house families or individuals who need special support and housing for a specific period of time. These units are part of the 10% public share, so they are owned by the local government in perpetuity.

Besides guaranteeing permanent affordable housing, this cooperative model aims to encourage the active participation of residents in the construction, maintenance and administration of the building. Cooperative membership requires residents to participate in the cooperative’s decision-making through the cooperative board, which seats are not restricted to residents but also representatives from the MCHA and local public authorities to keep the interest of residents and the community at large. Job-training in different areas is promoted in this model, as well as sharing skills with other cooperative members within the property in which they live, as well as other neighbouring cooperatives. Sweat equity is of great value. The equity generated by working for the benefit of the CHT may be exchangeable for lease subsidies, especially for those households with greater needs. In addition, this equity is acknowledged in another component of this hybrid model: the cooperative fund. A small percentage of the monthly fee is transferred to this fund and saved for community members leaving the cooperative. A proportional equity of their work and engagement during the leasing term in the cooperative is given back.

5. Strategies and collaborative frameworks for the coproduction of housing for todays and future generations

Since the 1980s the policies of ‘devolution’ have encouraged states and localities to formulate their own housing programmes. Decentralisation of resources and responsibilities to lower government levels, reducing federal involvement, have been promoted. Federal government is no longer the dominant player in housing policy. State and local governments, alongside non-profits, have adopted a central role in policy development and implementation. It is important to mention that even when state and local governments formulate housing programmes and provide funding, public agencies rarely build or renovate housing or provide housing services to residents. Most of the time, these provisions come from the private and the non-profit sector.

A number of community agencies supported by the Federal government, neighbourhood entities instituted by local government, and other local grassroots groups, which were formed to supervise and implement anti-poverty programmes, evolved over time into non-profit Community Based Organisations (CBOs). The most progressive ones were established with the central mission to reverse neighbourhood decline. Most of them were set as Community Development Corporations (CDCs). CDCs became strategic partners for the implementation of the policies of ‘devolution’. Since public and private institutions had little interest in impoverished neighbourhoods, the city transferred most of the responsibility to these non-profit corporations, which found an open turf and flourished, assisting neglected neighbourhoods with assistance from the city, state and federal governments. Later on, many of them established partnerships with foundations, financial institutions and other powerful partners, and eventually outgrewwith complex financial models for housing and social development. Today, CDCs constitute the largest segment of the non-profit housing sector.

While the devolution of power and resources has transferred responsibility for housing provision from federal to lower government levels, it has stimulated competitive policy-making in many jurisdictions. This competition has become apparent at the local level in the involvement of CDCs and CBOs. Benefits at the local level may be affected by the competitive political processes required by public programmes, as well as the non-profit leader’s political influences. In addition, rivalry between non-profits serving the same jurisdictionhas often been an issue preventing the following: firstly, collaboration and openness between non-profits addressing similar issues; secondly, innovative and tactical approaches to assist in the ongoing battle between powerful developers and resourceless communities; thirdly, delegation of power and resources to citizens; and finally the creation of local coalitions to envision, participate in and campaign for pathways leading to alternative housing models providing social, economic and spatial justice.

Considering all these facts and the rich legacy of housing programmes that emerged during the nadir of the city (tenant- and community-led housing programmes), one of the most feasible avenues through which to achieve a scalable impact is a direct collaboration between the city and the grassroots. The state must retake responsibility in order to mitigate the effects of this unprecedented housing crisis. Housing reform and progressive approaches have come at critical moments. Today we are experiencing conditions that neither the private market nor the non-profit sector can tackle. It is time for the government once again to assist in the production of decent and affordable housing for low-income communities through progressive programmes developed and managed in cooperation with tenants to maximise public and collective benefits. The proposed cooperative housing trusts developed through a hybrid tenure framework could make a difference, pulling together current public programmes, funds, and instruments, while recognising the agency and priorities of marginalised and vulnerable communities, rather than complying exclusively with for-profit and non-profit housing developers’s interests. This hybrid model would strengthen the capacities of local stakeholders to complement each other with valuable knowledge and assets, while reducing competition between local non-profit developers, since local cooperation is at the centre.

Local coalitions are crucial alongside a city-wide movement to raise awareness of the urgency and benefits of shifting the hegemonic housing paradigm—homeownership promoted by the state and supported by global finance. The most progressive housing programmes have come from visionary tenants, grassroots groups, community organisers and community planners who have urged public authorities to change paradigmsdominated by the interests of the market and the oligarchy, many times through direct action demonstrating transformative solutions. These gestures have evolved into institutionalized pilot programmes and subsequently expanded. The proposed initiative calls for the hybridisation of progressive property and housing modelsalready demonstrating to be effective, and the creation of collaborative local frameworks for its implementation and proliferation. This model intends, besides the provision of affordable housing for todays and future generations, preventing the ongoing takeover of housing by global real estate markets, hedge funds and private equity firms. It calls for housing for people not for speculation and profit making.Actionable strategies must come from different angles—including local authorities, non-profits, grassroots groups and citizens— and convene to achieve a common goal: housing all New Yorkers.

References

Kirby White (ed.), The CLT Technical Manual, National Community Land Trust Network, 2011. Available online at: http://www.cltnetwork.org/index.php?fuseaction=Blog.dspBlogPost&postID=1614

Daily Report, 4/21/2014, New York City Department of Homeless Services, 2014. Available online at: http://www.nyc.gov/ html/dhs/downloads/pdf/dailyreport.pdf

Policy Brief: Homeless Demographics in NYC, New York City Department of Homeless Services, 2003. Available online at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dhs/downloads/pdf/demographic.pdf

Archive

To see the Stage C Report from March 2012 please click here.

1 For more information, see Kirby White (ed.), The CLT Technical Manual, Portland: National Community Land Trust Network, 2011

2 For more information, see Kirby White (ed.), The CLT Technical Manual, Portland: National Community Land Trust Network, 2011.

3 This housing model has been developed by Cohabitation Strategies for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities. For more information about this model, research and development, please visit www.cohstra.org

Download this article as PDF

Gabriela Rendon

Gabriela Rendon is an architect, urbanist and a co-founder of Cohabitation Strategies, an international non-profit cooperative for socio-spatial research, design and development based in Rotterdam and New York City. Gabriela's work combines research, planning and strategic design. Urban housing, participatory planning, neighborhood decline and restructuring are among her research interests. Her latest studies center on the politics, practices and constrains of social and spatial restructuring through citizen participation in low-income neighborhoods in America and Western Europe. Previous research and design projects have taken place on the northwest Mexican border region. Gabriela is an adjunct professor at The New School in New York City. She has also taught on the postgraduate programme in Urban Studies at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, where she received a Masters in Urbanism and is currently working towards a Ph.D in the department of Spatial Planning and Strategy.

- Introduction

Jeanne van Heeswijk and Britt Jurgensen - Becoming Homebaked

Samantha Jones - Millionaire's Shortbread

Recipes by the Homebaked Chefs - Taking Space

Don Mitchell - Envisioning Public Cooperative Housing

Gabriela Rendon - Carrot Cake

Recipes by the Homebaked Chefs - Performance, participation and questions of ownership in the Anfield Home Tour

Tim Jeeves - 2Up 2Down/Homebaked and the Symbolic Media Narrative

Sue Bell Yank - Walton Breck White

Recipes by the Homebaked Chefs - Shankley Pie

Recipes by the Homebaked Chefs - A Creative Alternative?

Kenn Taylor - Homebaked Portraits

Mark Loudon - Colophon