Inhabiting Histories

Kate Hoffman and Ada S. Jaarsma

I. The past in the present

To call up the past in the form of an image, we must be able to withdraw ourselves from the action of the moment, we must have the power to value the useless, we must have the will to dream. Man alone is capable of such an effort. But even in him, the past to which he returns is fugitive, ever on the point of escaping him, as though his backward turning memory were thwarted by the other, more natural, memory, of which the forward memory bears him on to action and to life.

—Henri Bergson1

The past survives into the present, says Bergson. We inhabit the past, he explains in a claim that runs contrary to prevailing accounts of linear or chronological time. The past is not actually in the past but is embodied by dynamics and relations in the present, including those that give rise to our own movements. How, then, can we cultivate ways to call up the past, as Bergson puts it? And what are the two different forms of memory through which images of the past emerge?

One is the memory of contemplation and recollection. This memory slows us down and engages our consciousness. It opens up our normally distracted perceptions to what Bergson calls the unused or virtual resources of the past. This memory surprises us. It occurs, for example, when normally habitual movement is interrupted in some way, becoming conscious because it has failed to attain its anticipated end. As interruption and surprise, this memory generates the possibility of change and newness, of the unpredictable and of invention.

If we tune our awareness in the direction of these connections in and through the movements of time, what kinds of insights might emerge?

An epiphany: It was standing before me, right there on the

tarmac, when I was struck

by the realisation that these hunted whales have been living among us all along

as reincarnated airplanes. Side by side, the bodies of the plane and whale run

along the

same lines as relationships with humans; their scale, the movement of bodies,

fuelling

and re-fuelling and the constant need to hit the surface of ground or air, to

continue

on their paths around the globe.

Bergson asks us to notice, however, that consciousness, including conscious memory, can only retain the smallest trace of the enormous and dynamic history of life, and that consciousness requires tremendous concentrated focus, energy and effort. We actually need to prepare ourselves, focusing our attention, in order to tune ourselves in to these memories.

With careful detail and in-depth reflection, though, we can remember specific events, located at definite moments in time. And, Bergson promises, such recollection will open us up the unused resources of the past.

What kinds of unused resources might these be? And how might they make new ways of moving and living possible in the present, especially through the conscious and careful memory-work that leads, in turn, to installations and reenactments?

While attentiveness to history enables us to foreground details and stories, the leaps that allow us to imagine the past are always ultimately unpredictable, perhaps even involuntary in some ways. Above all, such creative leaps do not arise simply by amassing historical facts or archival documents. As Søren Kierkegaard points out, ‘A “more” cannot bring forth the leap, and no “easier” can in truth make the explanation easier.’2 When artists restage history, then, these material connections invite others to draw associations and forge analogies. Pulling together land, sea and air, for example, an art installation might call passersby to confront the relations between escaped slaves and sailors, whales and whalers, airplanes and evolution.

In the action of a re-enactment there exist three levels of experience; what is understood about the past, what and how things are chosen to be re-created, and the unpredictability of that present moment to be achieved only within the site and space of that newly re-enacted history.

There is a different kind of memory from that of consciousness, according to Bergson. This is the bodily memory of habit, in which the past is retained and even prolonged through regular and repetitive movement. Habit is a rote kind of memory, in which memories are activated without effort or conscious intention. Our bodies actually accumulate and live memory through habits.

We could say that the past is present in the life of living things because of habit: a living thing carries the accumulation of history in its body. Here, too, we can consider how our own embodied rhythms echo the rhythms of past lives. What might it look like to trace and capture such broad-based rhythms through drawings, cartography and sculpture?

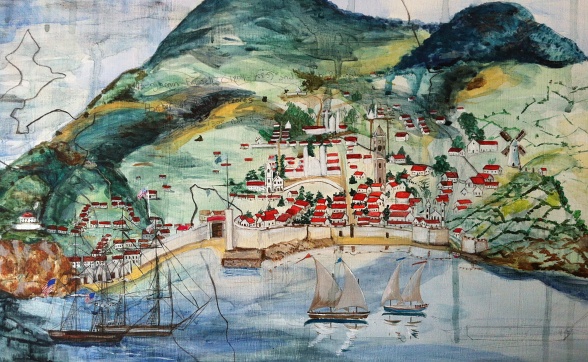

Within relations of exchange, bodies are interacting across space and time: bodies of individuals and bodies of larger systems of movement. We can draw parallels between whale migration, for example, the whalers in pursuit of whales as a fuel commodity, and the system of escape from slavery sometimes referred to as the ‘Saltwater Underground’: a network by which enslaved peoples escaped by sea. The body of the whale became a source of wealth as a commodity, intersecting with the mobility and displacement of people pursuing these creatures around the globe through the industry of whaling; in turn, the bodies of slaves could find means of escape in and among these shifting economies.

II. Land sea and air: changing definitions of life

Rather than individuals with discrete and bounded bodies,

then, we can affirm living things as essentially connected in time; these

connections emerge because of both habitual movements

and the conscious recollection of the past. Commenting on Bergson’s account of

habit, Elizabeth Grosz explains, ‘Where memory represents and imagines the

past, habit acts and repeats it.’3

And this philosophical accounting of memory points to a particular understanding of life itself.

We live in a world that is always changing, and so we need the anchor of habits to accommodate and coordinate with our environment. Without this kind of bodily repetition, we would lack the energy necessary for new and unexpected movements. Movements that are habitual and automatic allow us to conserve energy, making possible the very expression of free and unpredictable and new movements. Put simply, change is only possible because there is repetition in movement.

When we tend to repeat ourselves through habits, we can also change our movements and do things differently. And freedom emerges through these acts of innovation, acts that are unpredictable and creative, not because we have consciousness but because of the intelligence of life itself. All living beings are capable of opening up new movements and actions. Freedom and intelligence actually inhabit the body. We act out freedom; we don’t possess it or have it.

In 1845, Frederick Douglass published a memoir that he titled The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave . As Valerie Rohy points out, this title calls into question the chronological nature of the narrative itself. While ‘Douglass’ is a name only assumed in freedom, the text tells a story that anticipates the author that he will become. In other words, the title collapses the distinction between the before and after of the author’s own position in time.4

The past to which we return is ‘fugitive’, according to Bergson, calling to view the figures of slave, whales and lost moments of history. While the backward-turning memory keeps us in the past, the memory of habit propels us forward. If we take the memory of the past and project it into the future in the ways that Bergson describes, we might start to see whales as airplanes, in an unpredictable and unanticipated analogy. Perhaps the important point here is that we can strive not to capture memory but to enliven it with this forward-movement of associations.

This is a portrait made according to the proportions of the height and breadth of the orator Frederick Douglass. The photograph was taken from the exhibition Liquid Gold-Black Gold, the Golden Age of Whaling at the Greenleaf Gallery, Whittier College, Whittier, CA in 2012.

1 Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory , trans. Nancy M. Paul and W. Scott Palmer, Zone Books, New York, 1988, p.82–3.

2 Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety , ed. Reidar Thomte, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1981, p.60.

3 Elizabeth Grosz, ‘Habit Today: Ravaisson, Bergson, Deleuze and Us’, Body and Society, Vol. 19, Issue 2 & 3, 2013, p.228.

4 Valerie Rohy, Anachronism and Its Others: Sexuality, Race, Temporality , SUNY Press, Albany, 2009, p.xiv.

Download this article as PDF

Kate Hoffman and Ada S. Jaarsma

Kate Hoffman makes paintings, sculptures and installations that explore the social impact of time, site, and experience. Her current project examines the historical connection between the migration paths of whales, the Underground Railroad, abolitionists, and the effects of the Quaker's whaling empire over these systems. In addition to the dock acting as a literal site of exchange within her current work, Hoffman is interested to expand upon the idea and potential of the dock as a liminal space.

Dr. Ada Jaarsma is a feminist philosopher whose research focuses on the intersections of social theory and continental philosophy. She has become increasingly interested in the existential significance of risk, particularly for biopolitics and queer theory; her current project translates Søren Kierkegaard’s 19thcentury existentialism into post-secular critical theory.

- Editorial

Brent Bellamy, Vanessa Boni, Rosie Cooper, Laurie Peake - The Returns of the Past

Nadine Attewell - New Economies of Exchange and the Zombies of Industry

Brent Bellamy - Reading Infrastructure. Theme Park in Paradise

Eva Castringius - The Shifting Sightlines of Montreal’s Silo no. 5

Morgan Charles - Postindustrialisation in the Present Tense

Jeff Diamanti - Using Strategies as Tactics: Liverpool Waters and Irrationality in Banff

Ryan Ferko - Inhabiting Histories

Kate Hoffman and Ada S. Jaarsma - A postcard from Banff

Logan Sisley - Natural Histories

Rafico Ruiz - Everything and Nothing

Fiona McDonald - Docking Infrastructures

Florian Sprenger - How to Know About Oil

Imre Szeman - Elevation and Cultural Theory

Michael Truscello - An Exercise in Understanding Distance

Xinran Yuan - BRiC Library

- Colophon