Samson Kambalu: Play, Passion and The Gift

Posted on 13 June 2016 by Liverpool Biennial

Samson Kambalu, I levitate, 2016. Photo for Liverpool Biennial Instagram takeover

Liverpool Biennial 2016 artist Samson Kambalu works across different media to explore received ideas in art, history and religion. He spent a week in Liverpool creating a series of short videos using his method of ‘Psychogeographic Nyau Cinema’ – a combination of film and site specific performance – which will be shown as part of the six episodes around which this year’s exhibition is organised. Here Kambalu discusses James Bond, literature, The Gift, ruptures in time and how he discovered his passion as an artist.

Your background was initially in ethno-musicology and your practice as an art has changed quite a lot over the years. How would you describe this trajectory?

As a natural one. I was 23 years-old and an associate lecturer at the University of Malawi when I left the country for the Netherlands and then the UK. I expected to develop after my undergraduate. For me, process is very important. Artists think that it’s good to be known immediately after art school, but you have to pursue a certain process. You don’t want to be known straight away because actually the art world is very seldom to do with art. You should have already had enough time to think about your work before you enter, otherwise it can be a difficult place. I expected to go through several processes of change before I even considered myself as a professional artist.

The thing about art, unlike other professions, is that you want an authentic practice. For me that means passion. I trained as a painter, sculptor, musician, writer – so I had many skills but didn’t know which I was passionate about. The process is about trying to identify certain tendencies within your work. Mine has always been towards play.

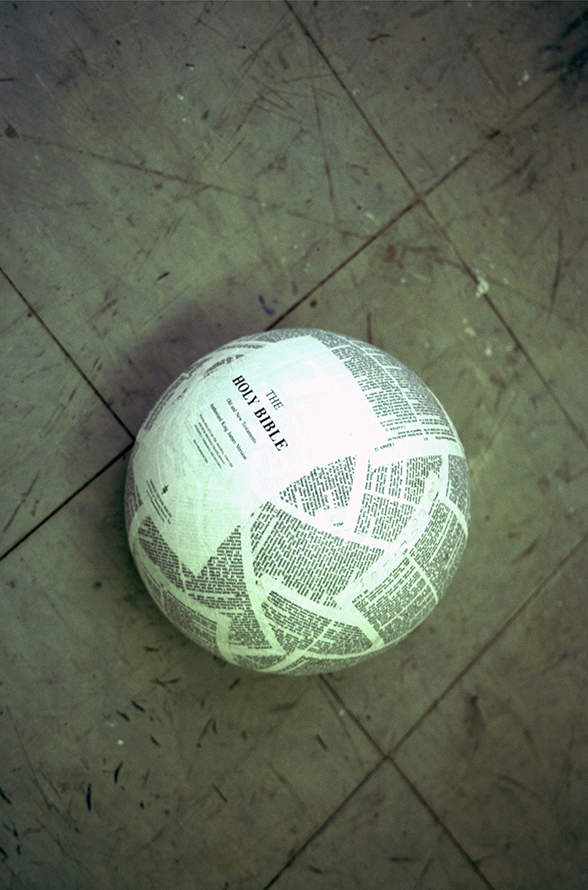

Samson Kambalu, Holy Ball, 2000. Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery

When and how did you realise this?

It was around the time I made Holy Ball, my first piece of conceptual art. The same playfulness that inspired this work was also present in both my writing and filmmaking. I used to wonder where it came from. I’ve since discovered that it’s very much to do with growing up in Africa and a certain conception of time there, which is very non-linear. I went to a western secondary school in Malawi so there was always a tension between my classical education and the non-linearity of everyday African life. I wanted to understand that.

But it was only by undergoing these processes that I realised my conception of time is different and that my instincts are still heavily influenced by the environment that I grew up in. Ultimately, I discovered that this was a passion. The only way for young artists to find their passion, their tendency, is to experiment. If you are passionate – that’s half the job done.

Samson Kambalu, One more look, 2016. Photo for Liverpool Biennial Instagram takeover

Could you explain the relationship between writing and filmmaking within your practice?

If you read my writing it’s very aphoristic. I don’t have a tendency for long prose. I like to cut. My favourite writer is Nietzsche. He writes in snippets. This idea of introducing ruptures within writing I also introduced into my films, which each lasted around 32 seconds. I wanted to be able to say a lot through a condensed poetic prose: to make a whole two-hour long film within a 32 second clip, to write a whole book within an aphorism or little anecdotal passage. I liked Nietzsche, Kafka and Bataille.

I think that poetry can reach the end of the universe, whereas with normal narrative you’d have to write thousands of books. I like semi-poetic philosophers so that even if you’re writing something straight, it still has a poetry. This again comes back to time because the aphorism disrupts the linearity that you would normally find in a novel. An aphoristic style is a series of ruptures. My films are the same. It’s not like you see a narrative; a beginning to an end. My films are passing moments you see in the street. Like a shower of time. The idea of linearity, of telos, of beginning and end is very Christian – the end of time, the end of the world etc. In Africa time is still very cyclical, based on the idea of eternal return.

How did you first become interested in making films?

I was busy trying to make it as an artist and writer at the time, and so found myself traveling a lot – around Germany, Switzerland, Austria, visiting museums and so on. Every place I went to I was a stranger. Eventually it became too much – just going to a city and observing, taking. When I began making films, it was a process of give and take. For example, I’ve come to Liverpool this week and I think I’ve given. I didn’t just walk around – I reacted and interacted.

I was doing these small rants, these poetic performances, even before I began filming them. When I came to Europe I used to walk the streets and just play, whether in the supermarket with a trolley or crossing the road; doing the unexpected. As soon as I started recording them however, they quickly became a conversation with the medium of film. The type I was thinking of was the Nyau Cinema from my childhood. Nyau Cinema emerged in Africa during the mid 1970s to 1980s, put together by travelling projectionists and shown in church halls or out in the open air (it quickly died with the coming of VHS tapes). It was a kind of mixed, heterogeneous form where films from abroad would be edited or cut to suit an African audience for who a traditional plot didn’t work. The African audience won’t wait for you. Some scholars have said there’s no such thing as audience in Africa. You can’t say: ‘sit there and watch me, passively’ – people simply won’t. Art in Africa always has to involve, to be a conversation between you and the audience. It’s not that they were simple or didn’t embrace art, it’s that they truly embrace the present moment. So if the film got boring, the projectionists in Malawi would switch to something more interesting. You could start with 007 then cut to Bruce Lee or Chuck Norris. You went for the best bits, and if there was too much conversation it would be edited out.

When I started editing my own films, I had the same aesthetic. I was trying to capture this ruptured time. That’s what I did for three years, just posting these short clips on Facebook without thinking I was making any sort of artful film. I just edited them the way I knew they should in order to be interesting. It was only later that I realised this tendency of play was there.

Samson Kambalu, Pickpocket, 2013 (film still). Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery

Do you think film particularly lends itself to play?

Definitely, it began as a playful medium. The middle classes didn’t embrace film as an art form to begin with because it was seen as vulgar, shown in cafés and smoking taverns. Only when it developed into a proper technology did they adopt it and cinema developed from playful non-linearity into the linearity of theatre. Linearity is well-loved by the controlling middle classes; it’s a form of propaganda that teaches you to be patient. The way you wait for a film to unfold is the same as how they tell you you have to work and work until you retire. Why should you wait? The moment is there but you go to films or watch TV and you’re being brainwashed to be patient. It’s all about commodity and profit control.

You don’t have this problem in Malawi because it’s a Gift based economy. By gift I don’t necessarily mean objects or goods but an attitude, a certain way of being with people. This is slowly changing but, in Africa, we still don’t think of time as money. Time can be valued as a form of expenditure without return. You can waste your time gloriously through play.

Samson Kambalu, 2016. Photo for Liverpool Biennial Instagram takeover

Could you explain a bit more about the relationship between play and the Gift?

The two are very closely connected. If I were to simply give you something, you would feel obliged to return the gesture in some way. There’s an idea of reciprocity, of exchange, that’s very cynical. It can even be controlling: as the giver I adopt a degree of superiority over you. Societies in Africa such as my tribe, the Chewa, introduce play to remove this element. In play, you can exchange things without each other realising. Take Holy Ball; if I stand in the middle of the road with a bible, people run a mile. But if I stand there with a ball, everyone loves me – even when I’m talking about God! They come up and share stories about their Christian upbringing and how they no longer have a bible and so on. People don’t realise you’re giving them something. They’re too busy engaging in play.

This can be the downside of my practice; people often don’t see that I’m being serious as well as playful because the two are not connected in Western thought. For me, play is a very serious thing. It’s the most profound thing you can do. It’s when I always imagine I am my real self. If you want to know the real me, watch my films.

What are you most looking forward to about being part of Biennial 2016 and having your work shown in the iconic ABC Cinema?

Making new connections with people.

Samson Kambalu for Liverpool Biennial Instagram

Watch Samson Kambalu’s short film, Pickpocket (2013), along with other examples of his work, or follow him on Twitter @kambalu_s and Instagram @kambalu to explore pictures from his Instagram takeover.

Samson Kambalu will make new work for Liverpool Biennial 2016 (9 July – 16 October). Find out more about his practice and previous exhibitions here.

Interview by Liverpool Biennial Assistant Curator, Sevie Tsampalla

Liverpool Biennial

55 New Bird Street

Liverpool L1 0BW

- T +44 (0)151 709 7444

- info@biennial.com

Liverpool Biennial is funded by

Founding Supporter

James Moores