Looking Backwards & Forwards: The 1985 Liverpool School Students’ Strike

Posted on 6 October 2016 by Liverpool Biennial

Koki Tanaka's recreation of the YTS 1985 School Students' Strike, 5 June 2016. Courtesy the artist

Koki Tanaka's recreation of the YTS 1985 School Students' Strike, 5 June 2016. Courtesy the artist

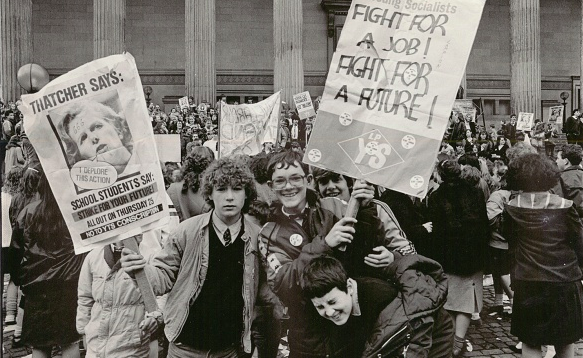

Explore different perspectives on the 1985 School Students’ Strike – a huge demonstration in Liverpool that saw 10,000 children take to the streets in protest against the Conservative Government’s Youth Training Scheme – which forms the basis for Koki Tanaka’s Biennial 2016 commission.

Koki Tanaka, Artist

When I first came to Liverpool, I felt lost in a way because it was so different from where I grew up. Liverpool Biennial Head of Programmes at the time, Rosie Cooper, told me about the leftie bookshop News From Nowhere, which is where I found Liverpool from the 80s by Dave Sinclair. I was looking through the photographs and found the School Students’ Strike. I’m familiar with many images of demonstrations or marches from history, of course, but I had never seen anything like this. Everyone looked so happy to be involved. There was this optimism around it.

Youth Training Scheme Protest, Liverpool, 25 April 1985. Photo courtesy Dave Sinclair

It occurred to me that the kids in the photographs would now be adults. When you’re a child you’re always looking forwards but as you grow older you become more cynical. I wondered what perspective they would have on the present now that the future has arrived. There are lots of parallels with what’s happening in education today, for example work experience schemes. In the School Students’ Strike Facebook page there’s a comment about history repeating itself.

Koki Tanaka, Provisional Studies Action #6, 1985 School Students’ Strike, 2016. Open Eye Gallery. Photo: Mark McNulty

Emy Onuora, Original Participant

I was quite politically active at the time. There was a real mood of political activism: the Tory party had come to power, Britain was losing a lot of its manufacturing industry and working class communities were losing the jobs that held them together. The School Students’ Strike was completely different to the relatively sedate, well-organised, trade union affairs I was used to going on. It was full of thousands of school students, mostly in their school uniforms, from schools all over: The Wirral, Kirby, Huyton, and even as far as Thornby. It set off from St George’s Hall about 20 minutes early and made it to the Pier much sooner than we’d envisaged. It didn’t take the route it was supposed to, just the most direct, so lots of the roads weren’t blocked off. There were hardly any police because they didn’t expect so many to turn up. The atmosphere was electric – I don’t really remember anything like it before or since. The demonstration resulted in the Conservative party backing down and the plans for forcing young people to do Youth Training Schemes were scrapped.

Emy Onuora. Photo: Richard Stonehouse / Getty Images

Even then, if you had a decent set of qualifications you could find work, all be it at a relatively low pay. That certainly isn’t the case now. Lots of young people are struggling for the independence just to rent their own place and many are on zero-hour contracts where their work patterns and employment rights are consistently undermined. My kids are now at the age of the students who went on strike and I’d really support them if they wanted to as well, perhaps around tuition fees or campaigning for real jobs with real prospects. I’d even give them a note to say they were taking the day off school to campaign. I think that’s a good education in itself.

Sevie Tsampalla, Curator

I remember that at an earlier stage of our exchange, Koki briefly considered his work within the Monuments from the Future episode in this year’s Biennial. With a slight twist to our invitation, he wondered: “What if we replaced Monument by Moment?” Looking back, this ‘exercise’ based on the proximity of the two words, was already hinting to some of the questions that his project would address. How do we remember together, how do we revisit history, and what are the politics involved in the public manifestations of these acts?

The moment he chose may have come from the city’s past, but beyond commemorating or feeling nostalgic about it, his project invited us to think and learn about coming together. For me, it is a privilege to have worked with an artist that approaches with such genuine curiosity and sensitivity what this togetherness can mean, both in the then and the now. I also remember how amazed we were that Rachel and Pamela, participants of the strike, were able to recognise themselves and their friends among the endless sea of young protesters against the YTS, when we showed them Dave Sinclair's photographs. This was not a moment that had haunted them, but that continues to resonate and generate beautiful discussions and new relations.

If it was the future that had the power to mobilise 10,000 children to take to the streets, could it be that each time we revisit this moment, perhaps we find ourselves always in the future?

Youth Training Scheme Protest, Liverpool, 25 April 1985. Photo courtesy Dave Sinclair

Visit Koki Tanaka's display at Open Eye Gallery until 16 October, open daily 10am–6pm, free entry.

Liverpool Biennial

55 New Bird Street

Liverpool L1 0BW

- T +44 (0)151 709 7444

- info@biennial.com

Liverpool Biennial is funded by

Founding Supporter

James Moores