Time Travel and the Politics of Water: Rita McBride at Toxteth Reservoir

Posted on 5 October 2016 by Guest Blogger

Rita McBride, Portal, 2016. Toxteth Reservoir. Photo: Joel Chester Fildes

Laura Rushton reflects on Rita McBride’s giant laser-light sculpture in the Victorian Toxteth Reservoir and the political significance of its setting.

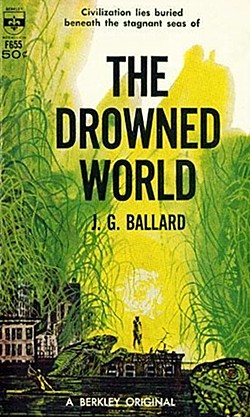

“In the early morning light a strange mournful beauty hung over the lagoon; the somber green-black fronds of gymnosperms, intruders from a Triassic past, and the half-submerged white buildings of the 20th Century still reflected together in the dark mirror of the water, the two interlocking worlds apparently suspended at some junction in time, the illusion momentarily broken when a giant water-spider cleft the oily surface 100 yards away” – J. G. Ballard, The Drowned World (1962)

For Liverpool Biennial 2016, artist Rita McBride has been commissioned to produce a large-scale, site-specific installation inside the derelict Toxteth Reservoir, which is one of the first over ground reservoirs of its kind in the world. One of the most popular and accessible works in the Biennial this year, McBride’s Portal uses the science fiction idea of time travel to consider the history of the reservoir and the politics of water.

Portal consists of eight green, high-strength laser beams, shot from either side of the reservoir, in between one of the central arches of the vaulted ceiling. Based on a mathematical formula, the lasers cross over in the centre in a formation which is described as “a passageway comprised of exotic matter that does not follow the known laws of physics; it bends time and space and allows instantaneous travel to the far reaches of the unknown.”

As you watch the lasers, you begin to notice a shimmering, glittering quality to them which you come to realise is the product of the light travelling through water vapour in the atmosphere. This, coupled with the constant drip of water leaking in from the roof and echoing around the cavernous space, re-iterates the fact that the reservoir once used to be full to the brim with water.

Rita McBride, Portal, 2016. Toxteth Reservoir. Photo: Jerry Hardman-Jones

McBride’s previous works, including small sculptures such as End to End (2004), which resembles an architectural model, or Mae West (2006), an incredible 52-metre high public sculpture, betray a strong interest in the relationship between art and architecture and the complex power structures it reveals. When bearing this in mind, Portal can be read as taking its meaning from the relationship between the lazers and their context – not just in terms of the architecture of the building, but the historical, social and cultural relations that the reservoir represents.

Rita McBride, Mae West, 2011. Photo courtesy Konrad Fischer Gallerie

The reservoir is a politically charged place. Built in 1845, it is a cavernous space roughly half the size of a football pitch. It has four thick walls hewn from large brown sandstone blocks, with a tower at one corner. Inside, the vaulted ceiling is held up by a series of steel columns, on the side of which a water line is visible, where the water has mottled the surface of the steel.

Toxteth Reservoir

It was originally built to tackle public health issues, amid an outbreak of cholera and rising concerns about the lack of sanitation within the rapidly expanding inner cities of the Victorian period. One of the earliest examples of engineering for public health purposes, it was gravity fed by water from Rivington Pike in the West Pennines, and supplied residents of south Liverpool with a source of clean water for over a hundred years. De-commissioned in 1997, when three access doors were put in by English Heritage approved stone masons, the site is now a Grade II listed building.

Some of the locals have interesting stories about growing up near the reservoir, including one man who told me how he and his friends would descend the spiral staircase to row around on top of the water, in a small dinghy. It is a place which seems to capture the imagination and bring out the storyteller in people.

There have been numerous plans to redevelop the building: varying from transforming it into a historical tourist attraction to children’s play area, and even building a giant glass pyramid on the roof to house a restaurant. The current owners, local community group Dingle 2000, are hoping to get the roof water-tight, install a visitor’s centre, and make the reservoir a new tourist attraction and community event space for the city. However, amid the current climate of austerity, and the difficulty in acquiring public funding for such community projects, the reservoir remains a politically charged place.

As a ruin, the reservoir occupies a unique place in the imagination. As Tim Edsenor wrote in his 2005 book Industrial Ruins; Spaces, Aesthetics and Materiality: “Ruins do not merely evoke the past. They contain a still and merely quiescent present, and they also suggest forebodings, pointing to future erasure, and subsequently, the reproduction of space, thus conveying a sense of transience of all spaces.” In other words, whilst ruins make a visitor question the history of the building, they also make him or her consider the future. If a building built in 1845 to store and distribute water for the local area is being used in 2016 to display a laser installation in an international art festival, what can we speculate about our contemporary buildings and what the future may have in store for them?

McBride has a deep interest in science fiction, having edited and compiled several faux science fiction novels herself – including Futureways (2005) which imagines the Biennale of a future civilisation. Linking in with the overarching themes in this year’s Liverpool Biennial, of alternative narratives and fictional worlds, visitors to the reservoir invent their own fictional narratives about how the reservoir came to be drained.

J. G. Ballard’s early 1960s sci-fi novels The Drought and The Drowned World come to mind – in which former industrial waste leaks into the ocean causing extensive drought. Rivers and lakes dry up and whole populations flee to the oceans in search of water. In the latter, the melting of the polar ice-caps causes western cities to become submerged in a network of tropical lagoons. Written two decades before worries about climate change and the resulting wide-spread public attention, these novels now seem like prophecies of global warming’s terrifying conclusion.

June 2016 was the 14th consecutive month of record-breaking warm temperatures globally, whilst according to NASA, both August and July 2016 tie as the hottest months globally since records began. As water becomes scarce in some areas, and other parts of the world become flooded, it will take on a political importance so significant, in a way that the Victorians who built the reservoir would not be able to conceive.

In 2013 Peter Brabeck, CEO of Nestlé, claimed that water is not a human right and should be privatised. While Toxteth Reservoir was built to supply local citizens with clean water, perhaps reservoirs of the future will be built to stockpile water, with it becoming a powerful commodity much in the way that oil is now.

Portal is a work which is informed by its context of the reservoir. Like the best science fiction, McBride’s Portal uses a hypothetical situation to explore real life anxieties within society. Built at a time of social-upheaval to match our own, with the intention of improving the lives of locals by providing a clean supply of fresh water, it is the perfect place to consider history and the future of the politics of water.

Visit Portal at Toxteth Reservoir until 16 October, open on weekends, 10am–6pm, free entry.

Liverpool Biennial

55 New Bird Street

Liverpool L1 0BW

- T +44 (0)151 709 7444

- info@biennial.com

Liverpool Biennial is funded by

Founding Supporter

James Moores