Cosmos, the Time Before Time and the Work of Arseny Zhilyaev

Posted on 5 October 2016 by Liverpool Biennial

Arseny Zhilyaev, The Last Planet Parade, 2016. Granby Street. Photo: Mark McNulty

Using artistic, political, scientific, and museological histories to uncover and propose potential futures, Russian-born artist Arseny Zhilyaev explores the space between fiction and non-fiction. For Liverpool Biennial 2016, Zhilyaev created The Last Planet Parade, a stained glass window and a small museum-like display housed within a terraced house on Granby Street in Liverpool 8. We catch up with the artist to find out more.

Tell us a little bit about your practice and the piece you have created for Liverpool Biennial?

I decided to make my commission about an amateur astronomer, whose family used to live in Granby during the 1970-90s. This fictional character began to develop a fascination with space and the cosmos after his father’s enchanting encounter with Yuri Gagarin. Gagarin was a Russian Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who became the first human to journey into outer space. The encounter occurred during Gagarin’s UK tour in 1961, when he paid a visit to Manchester's factories, where the farther of my amateur astronomer worked.

Before becoming an astronaut, Gagarin studied steel-work and worked in a foundry. It was logical for a representative of a communist country to meet with workers as well as the Queen, and the visit to Manchester was made with the help of local trade councils. So this was the starting point for me.

Yuri Gagarin with worker: two countries, two foundry workers. Image courtesy Working Class Movement Library

Through his interest in space, the boy began making mystical observations from his room in Granby. He started to recognise an odd phenomenon, something like a repeated movement of planets each year that he called called a ‘Planet Parade’. Over time, our hero concluded that this was an artificial performance of some kind, like a ‘re-enactment’, to use contemporary art terminology, by a more advanced civilization. Its aim was to resurrect, as some kind of cosmic-scale art piece, the doomed trajectory of their motherland planet as it travelled towards a black hole. But this is all we know from the boy's diary. In order to try and express the extraterrestrial beings’ feelings, he produced a piece of stained glass. This he used to try and make contact, by means of light, with the distant past and future of our universe.

How important is Granby Street as a venue for your work? Has the venue shaped the piece in any unexpected ways?

Granby Street is an amazing place. I like its calmness, and ethos of involving and helping people. It is nice that Liverpool still has such type of relationships. It is really uncommon today. I hope that one day it will once again become a fully alive place, without the gentrification that often comes through artist activity. It seems the strength of the community here will resolve all difficulties.

Painted windows in Granby Street area. Photo: Arseny Zhilyaev

What drew you to the apocalyptic nature of the piece? What wider comments does it make on current society?

Well, in my mind, The Last Planet Parade is mostly about our limits in terms of perception and conceptual reception of art. For instance, how can we feel or understand a type of art that overwhelms us? Either due to its size or perhaps because it exists in a medium that is beyond the limits of human perception. Religious art possibly provides us with some insight into the representation of such things. Religion, independently from our relation to it, has an intuition of creation that is beyond our access.

While religious art was something that used to lead us away from, let's say, reality, 20th century artists fought against any type of representation at all in favour of direct access to the materiality of our universe, here and now. But all that we know about this subject today is limited to the representations made by scientists, previously known as magic. Our present experience is utterly limited and based on an illusion made by humans, which is absolutely incomparable with the order of things. So the piece is not so much about society, as it is about us and the space we inhabit within the universe.

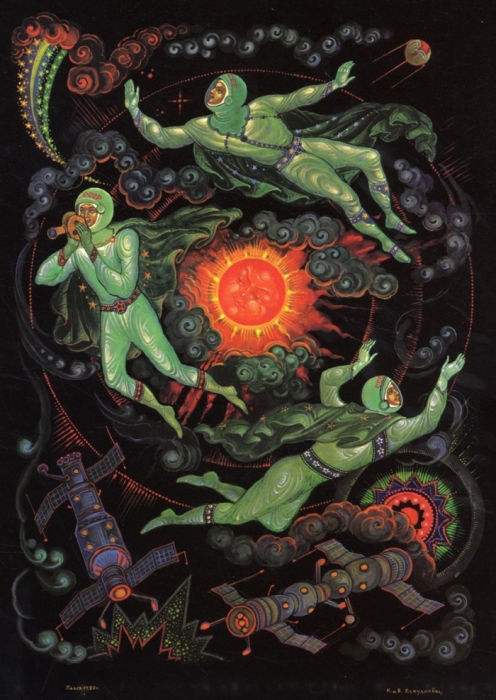

Son of Russia. Illustration by K. Kukulieva and B. Kukuliev

Why did you choose a museological approach to present a piece about an imagined future? What significance does this format carry?

I think there is a way to accelerate the whole project of contemporary art in order to bring us to a break-through into the future. This way lies in reflection upon exhibitions and the museum as a medium. The museological approach is in a way a statement that criticizes the fetishisation of critique. We can learn a lot from analyzing the formal compositions of both the analytical and weird – by today’s standards – Soviet museum exhibitions created by representatives of avant-garde museology. Plus, in my case, we are dealing with museums and exhibitions in the future. This approach is a possible reconstruction or a possible scenario for art history and the political and social conditions it provides.

Arseny Zhilyaev, Cradle of Humankind, 2015. Courtesy the artist and V-A-C Foundation. Photo: Alex Maguire

I will describe how this works. In 2015 I did a project in Venice which was about a distant future museum called Cradle of Humankind. In an imagined scenario, humanity had left Planet Earth many years ago and turned it into a network of museums dedicated to the history of human civilization, starting from the Big Bang and the origins of life. Visitors to the museum could learn about the history of the interstellar human empire by examining some of the achievements of its greatest citizens, and purchase services from the museum corporation.

There was a mysterious golden sphere, for instance, which was a prehistoric spaceship said to have brought life to Earth from outer space. The motif of the geodesic sphere was taken from Buckminster Fuller’s pavilion built for the American National Exhibition in Sokolniki Park in Moscow in 1959. His concept of ‘Spaceship Earth’ was an independent development of one of the co-founders of the Russian Cosmism doctrine, Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, whose ideas formed in the late 19th century. Fuller’s sphere was an important symbol for Soviet kinetic artists who tried to continue the tradition of Russian Cosmism in a new historical period, and connect to its technical aesthetics.

Arseny Zhilyaev, Cradle of Humankind, 2015. Courtesy the artist and V-A-C Foundation. Photo: Alex Maguire

Or, as another example, in the museum shop visitors were able to order DNA investigations into their dead relatives and choose a new, more advanced body for them – of course if they have enough money to pay for it. To sum it up, it was a speculation on the possible realization of certain radical ideas about human development, but under the same capitalist political and economic order that currently exists.

What did you do on your visit to Liverpool and what are your impressions of the city?

What I remember most about Liverpool is its people. I was lucky enough to meet members of the Granby community and work with locals for the Biennial. People in Liverpool are different from, you know, London 'posh' style. Once I came across a far-left Trotskyist newspaper in an ordinary Indian restaurant. You can't imagine something like that happening in any place in the world, except maybe areas controlled by Cambodian red partisans. I also found the way that people treated you during the official presentation of the Biennial very unusual. Ordinary people, who were not especially engaged with art, were very active in asking questions about artists’ work and giving advice about Liverpool. I remember realising how important the Biennial was for them, because they treated it as a part of their life. They don't separate it from other cultural, urban or general activity in their city. I have not seen such a high level of fusion before.

Finally – where would you time travel to if you could?

I would prefer a machine that allowed you to travel to the period before time, before the Big Bang, into the pure intensity of theinflationary phase. I would also like to encounter the Big Bang itself; I guess it is an ideal museum because you have all times simultaneously expressed in one space and moment. It is maybe out of an unconscious attempt to repeat this that all museological representations and art installations emerge.

Questions by Eleanor Hall

Visit Arseny Zhilyaev's display on Granby Street, Liverpool 8 until 16 October, open daily 10am–6pm, free entry.

Liverpool Biennial

55 New Bird Street

Liverpool L1 0BW

- T +44 (0)151 709 7444

- info@biennial.com

Liverpool Biennial is funded by

Founding Supporter

James Moores